Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMOVIES

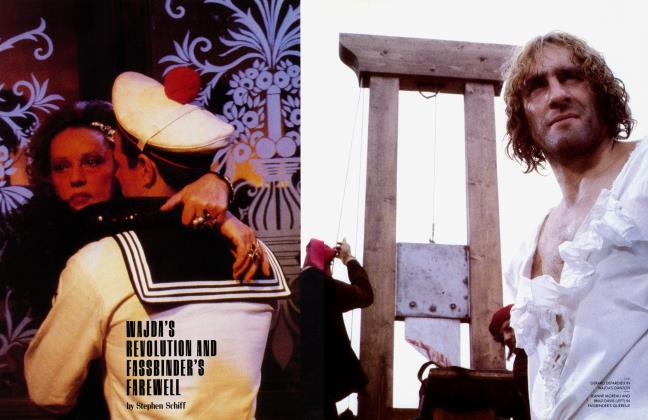

April 1983 Stephen Schiff, Carol FlakeTHE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT, directed by Peter Greenaway (United Artists Classics). The obscure British writer-director Peter Greenaway has carved out a precarious niche for himself with a series of avant-garde films that avoid the easy enticements of narrative. But The Draughtsman’s Contract, his latest, is a murder mystery set among the pampered, prurient aristocrats of the seventeenth century, and it’s determined to tell a story. It even has stars. There’s Janet Suzman, all pomp and dignity as the regal Mrs. Herbert, whose husband, traveling on business, has left her in charge of his estate for two weeks. And there’s Anthony Higgins as the handsome, self-adoring, and altogether insufferable draughtsman Mr. Neville. Mrs. Herbert hires him to draw pictures of the estate—and in the process to glorify her husband. She’ll pay him, of course, and not just in pounds. The draughtsman insists on a clause in his contract letting him have his way with her for the duration of his employment. But strange things are afoot in the gardens. Someone is leaving ladders and bits of clothing strewn about, and since Mr. Neville is at once unimaginative and terribly fastidious, he faithfully reproduces these odds and ends in his drawings. Only later does anyone realize that, taken together, the drawings constitute evidence of a murder.

The Draughtsman’s Contract is what you get when you cross Blow-Up with Barry Lyndon: it’s pretty and sexy, rigorous and clever. Greenaway has captured the spectacle of morning sun creeping across endless manicured lawns, the opulence of a candle-lit dinner on the manor’s porch, the splendor of fountains and topiary and ancient stone. He has also captured the convoluted snippiness of seventeenth-century insult; in fact, his dialogue is so piss-elegant that it’s nearly impossible to find the characters beneath their circumlocutions. But The Draughtsman’s Contract is never finally enthralling—it’s much too cold for that. Still, the chilliness has its purpose: Greenaway’s goal is less a diverting narrative than a philosophical/aesthetic discussion. This is an entertainment for people whose idea of a good bedtime read might be Godel, Escher, Bach, and for them the heady ironies should prove amusing. The search for patterns and interpretations, the lust to know more than what is simply seen—this is the film’s true subject. As we peer at Greenaway’s greenery through the transparent grid Mr. Neville uses to draft his drawings, we find ourselves sniffing out hidden meanings and clues, just as the characters do when they try to solve the murder. And the cream of Greenaway’s jest is that he’s continually catching us at it. Staring into his bright, mysterious tableaux, you can feel your nose being merrily tweaked.

STEPHEN SCHIFF

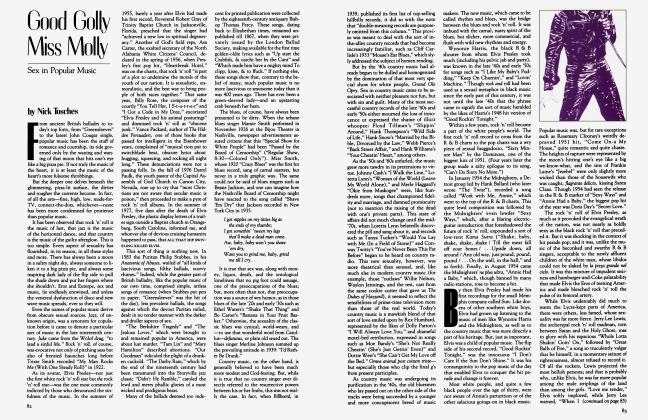

SAY AMEN, SOMEBODY, directed by George T. Nierlenberg (United Artists Classics). "The Devil can tear your stockings and flatten your tires,’’ warns a preacher in this warmhearted but unsentimental documentary about gospel music. Satan, it seems, can invent many an obstacle to getting to the church on time. But there’s one force the Old Tempter can’t hold back, and that’s a sanctified voice. "The Lord anoints your voice,” says 78-year-old Willie Mae Ford Smith, an early pioneer of gospel who can still shake a rafter or two when the spirit is willing. “I may have cracks in my voice as wide as the Mississippi,” she admits to the camera, “but that old river keeps on flowing.” And when Willie Mae sings “Never Turn Back” during a special service held in her honor, there are few in the church who aren’t swept up in the current.

The world of gospel music is a matriarchy that has been ruled largely by such formidable women, the colossi of faith, ample of voice and girth. Although golden-toned male quartets brought heavenly harmonies to the choir loft, it was the spine-tingling swoops and moans of the great female soloists that popularized the music. And since gospel music, at least in the beginning, was a form of evangelism, women did not always have to confine themselves to the amen corner; they witnessed from the pulpit in both sermon and song. Willie Mae chides a conservative grandson for his skepticism about women preachers: “If God can make a jackass talk,” she observes ironically, “how come he can’t make a woman preach?” In any case, it’s the younger singers who seem to have a real problem with priorities. We see Delois Barrett Campbell (of the Barrett Sisters) in an uncomfortable exchange at breakfast with her preacher husband, who is urging her to give up a career with her sisters to help him in his storefront ministry. Diplomatically, she parries his complaints with an offer of sausage to go with his eggs.

The other “star” of the film is a frail little pea pod of a man whose voice is now but a silvery whisper. Without Thomas A. Dorsey, the father of gospel music, black church choirs might still be confined to stately spirituals and mournful hymns. In the 1930s, Dorsey, a popular bluesman, and his collaborator Sallie Martin jazzed up the good news of salvation with the badnews rhythms of the blues. Dorsey’s music let you tap one foot while the other rested on higher ground. As Mahalia Jackson observed, he was the Irving Berlin of gospel. But he was also the Bach and the Beethoven. Most of the standards in the gospel repertory were written or adapted by Dorsey, including “Peace in the Valley,” the song of transcendent hope that Elvis Presley could not sing without stirring floods of tears.

The jubilant music that we have come to associate so closely with black Christianity was not welcomed at the altar with open arms. Although congregations responded with resounding amens, preachers didn’t always approve of songs that came so near to the Devil’s music. “I’ve been thrown out of some of the best churches,” Dorsey recalls, with a hint of pride. Nowadays, of course, it’s hard to imagine how anyone could find even a trace of devilment in such spotless testaments as Dorsey’s “If You See My Savior. ”

When “the professor” sings his classic “Precious Lord” at the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses, the scene lifts the film into the sublime. He makes his way slowly and painfully to the podium on an aluminum walker, a slight figure amid a sea of beaming women in white who are singing the children’s Sunday School song “Jesus Loves Me” as a triumphant anthem of unconditional love. They let Dorsey begin, “Take my hand,” and then they take up the melody when his wispy falsetto begins to falter. “Watch it,” he cautions with a waving finger during a dramatic pause. He’s ever the choir director. As the voices soar, “Through the storm, through the night, /Lead me on to the light,” those not privy to such joy, such comfort, must feel like outsiders in the promised land.

CAROL FLAKE

WE OF THE NEVER NEVER, directed by Igor Auzins (Triumph Films). In American westerns the noble horseman has to keep a move on, lest some God-fearing woman tidy up his bedroll. It was wives with their boiling caldrons who tamed the Wild West. But in Australian films it’s more often the high-spirited woman whose untidy independence is in jeopardy; Australian heroines are more interested in adventure than in housekeeping. Feisty hoydens appear to have a greater affinity for the unknown than do roughneck men; men run cattle through the wilderness while women succumb to its mysteries.

The otherness of aboriginal life and the coming of age of rebellious women, both common themes in Australian movies, are not so incompatible as they seem. We of the Never Never, based on the 1908 autobiography by Mrs. Aeneas Gunn, combines the two. The newlywed Mrs. Gunn accompanies her husband into the outback with the spunky zeal of a missionary and winds up a resolute widow among fatalistic natives—a story that seems a cross between Picnic at Hanging Rock and My Brilliant Career. But director Igor Auzins aims for the no-nonsense narrative and sweeping panoramas of John Ford rather than the surreal tableaux of Peter Weir or the charged interiors of Gillian Armstrong.

Jeannie Gunn (Angela Punch McGregor), plain but luminescent of feature, contains her gasp of disappointment when she arrives with Aeneas (Arthur Dignam) at the primitive cattle station in the outback that he is to manage. The hired hands, however, hardly bother to disguise their disgruntlement at the intrusion of a lily-skinned female into their dusty domain. Jeannie, who soon tires of maintaining her little house on the prairie, must turn to the nearby aborigines for companionship.

Jeannie’s battle to raise the consciousness of the stockmen about both women and aborigines stirs up rather predictable protofeminist and civil-rights issues. When Jeannie and the stockmen discuss cosmology with the aborigine Goggle Eye, the old black man asks slyly, “If the white man’s God made everything, why didn’t he make them a bush of their own?”

Director Auzins alternates such interludes with lingering shots of the wild, alien landscape. Jeannie walks forlornly through fields of petrified termite hills looming up like a miniature Monument Valley. In one marvelous episode the cattlemen vie with the aborigines to imitate the sounds of the bush, creating a witty cacophony of birds, frogs, and dingoes. There are endless scenes of horses and cattle thundering by, raising clouds of dust that refract the sunlight into a pastel haze, But unlike John Ford’s choreographed hordes, Auzins’s energy-on-the-hoof scenes seem repetitive rather than lyrical. He lacks Weir’s ability to put a spell on the action so that we can actually feel the hypnotic pull of the land. By the conclusion of the film, instead of reveling in the timeless allure of the Never Never, one is tempted to feel a twinge of relief at escaping it.

—C.F.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now