Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhat's wrong with our radicals?

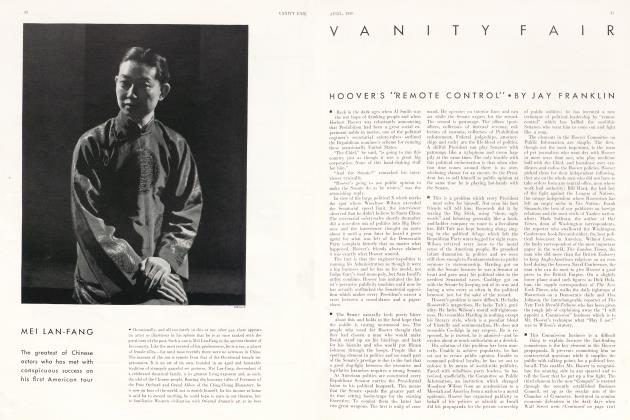

JAY FRANKLIN

What's wrong with our radicals?

They've heen presented with the biggest chance in history for getting away with a real change in the old set-up and they have got precisely nowhere.

They have had depression for five years, millions of unemployed, misery in the midst of plenty—all the raw material for a home run with the bases full and they haven't even gone to bat.

The Communists have never got much farther than blowing off steam in Union Square and raising a stench in a quiet gentlemanly way about the "Scottsboro boys."

The Socialists have never been able to reach very far beyond the German-Jewish groups in a few of our larger cities.

The home-brewed hell-raisers have never done much more than yell for the Bonus, for the Townsend Plan, for the Epic Plan, for Technocracy or what-have-you and have always been among the yes-men when the votes are counted.

What's the reason for this flop? It isn't enough to say that they trust Roosevelt, because most of them curse him out in terms which would turn a Tory green with envy. It isn't enough to suggest that they don't know what they want, for if there's one thing a radical does know, it is precisely that. IL isn't enough to complain that the game is rigged against them—that laws, newspapers, banks and sheriffs won't give them a fair break—for that has always been the fate of radicals since the beginning of time and they should take it for granted.

There are other reasons, much deeper reasons, for their failure to combine on the few, broad, simple things which need to be done and which cannot be done without a radical demand for them.

The first reason is that the true radical is incapable of cooperating with any other radical at any time. The Communists are proverbial for their marplot mischief and would rather do what they call "broaden the base of the class struggle"—that is to say, make trouble—than help a decent labor union win a justified strike. The Socialists are worse, though pretending to be better. In 1933 they held what they called a Continental Congress of radical groups at Washington, 1). C. The whole affair was steamrollered from start to finish and people who had come in good faith left with the feeling that Norman Thomas & Company had played them for monumental suckers. Karl Marx was a pretty shrewd old German Jew, but he flourished before the age of mass-production or effective labor unions, not to mention electric power, chemistry, and the photoelectric cell, and his views are simply out-of-date. To attempt to impose them, as gospel, on the spiritual descendants of Jefferson, Lincoln, Thomas Edison and Henry Ford is ridiculous. Yet that is the whole Socialist — and Communist — programme, that and the acceptance by the American people of absolute leadership by the watertight little cliques in New York -or Moscow—who run the entire Marxian show.

The American radicals are no better in this sense than the Marxians. Intimate contact with two or three of their leading lights has convinced this observer that they cannot lead, will not follow, and refuse to cooperate.

George W. Christians, leader of the White-Shirt Crusaders, the American Reds and the American Fascists, of Chattanooga, Tennessee, at one time had a following which might have amounted to three million voters, including general sympathizers. Instead, by a policy of double-crossing and smashing his local movements—in order to obtain publicity for his ideas—his movement has degenerated into a one-man show .

Howard Scott, who in the winter of 193233 emerged as the leader of Technocracy, had the greatest chance of any modern American to put across a new idea. It had received a wild-fire wave of endorsement all over the country and could have commanded the sympathetic support of the most conservative and socially responsible force in American life. A group, headed by Langdon Post, now Mayor La Guardia's Tenement House Commissioner, had been built up to give Technocracy protection and support while it was evolving a concrete program. What did Scott do? He made a public exhibition of himself at the meeting which had been arranged for him to address the leaders of American business. He split tin group with which he was working, tried to discredit and destroy his former associates, and ended only when the whole idea which he had dramatized had fallen into ridiculous disgrace.

Not only do American radicals refuse to cooperate, even with their friends and supporters, they pig-headedly refuse to combine to work for the same immediate objective. I have heard a young radical editor address a meeting at which several liberal groups had agreed in principle to support the establishment of government control of credit as being something basic to what each group wanted. The editor said that he refused—he was speaking for the FarmerLabor group—to work for what he wanted with any other group unless that other group first endorsed all of the principles of his group. And I have seen a pallid, bespectacled youth, with soft white hands, who had never spent a summer away from Manhattan Island, proclaim his leadership of a large Mid-Western agricultural group, in whose name he defied the government— denouncing Governmental regimentation— to block the embattled farmers from a program which would have meant the most intolerable regimentation for everyone who was not a farmer.

(Continued on following page)

They have their isms and their spasms and are no more to he weaned from the one than from the other. Any statesman who builds on their support will go bust. Any politician who tries to combine them will go mad. They are the lunatic fringe—crazy, not because their ideas are necessarily unsound, but because their methods of achieving those ideas are automatically self-defeating.

In the third place, our radicals are abysmally and short-sightedly sentimental. To succeed in politics you can he a great moral enthusiast, like' Savonarola or Wilson, or you can he a cold-blooded realist, like Lenin or Hamilton, but you cannot be a sentimentalist.

The radical mind is weevilly with soppiness. He moans over Sacco and Vanzetti, he agitates for Tom Mooney, he groans about the Scottsboro negroes. Yet, if he is right in his premises of a class-war, he ought to regard these cases as perfectly logical incidents in his struggle against society. His sentimentality has curious streaks of blindness, lie yells to high Heaven about the few hundreds of people killed in the Hitler Revolution and shrugs his shoulders when asked about the millions killed in the Soviet Union, the ''liquidation of the Kulaks, the forced labor camps, the political prisoners and such who are butchered to make a Bolshevik Holiday.

And the radical lives in a world, not of people, but of mythological monsters: of Bankers, of the Power Trust, of Bourgeois Exploiters, of Imperialists, of Class-Conscious Proletarians never of plain, puzzled men and women who are doing their best with the system into which they have been born and who might respond with overwhelming fervor to any proposal to change it for the better. The radical never even admits the possibility that the Catholic Church may he right when it says that nobody is all good or all bad. To him, the possession of property, power or privilege by others is an unpardonable offense which can in no way be atoned for by the surrender of property, power or privilege hut must he punished on earth and at once.

Last—and most important of all—the radical has no imagination. He is like Owen Wister's miner who made a gold strike, swaggered into a smart restaurant and yelled: "Damn it! give me forty dollars' worth of ham-and-eggs." His Utopias are always ham-and-egg Utopias, places where people will keep on living just about as they do now: jammed together still in bigger cities, sheltered in more sanitary tenements, eating bigger portions of corned beef and cabbage, attending free super-films from Hollywood and thronging to still larger mass-meetings in Union Square at which the radical police "cossacks" will break up conservative top-hatted rallies.

He has no concept of real radicalism, which is calculated by accident or design to change the living habits and enlarge the possibilities of human beings. He does not see that true radicalism may consist of breaking up the large cities, of ending labor-unions and mass-meetings by removing the peculiar conditions which gave rise to them, of creating an entirely new way of life for both the farmer and the workman through hydroelectric energy and industrial decentralization.

If this sort of thing is radicalism—and what could he more radical?—then our real radicals are not the men who say they are, hut the people they denounce as reactionaries. Henry Ford, for example, has done more to change the living habits and viewpoint of Americans than did all of our Presidents from Grant to Taft. Thomas Edison has made possible a social revolution more profound than anything proposed by Thomas Jefferson or Henry George, the SingleTaxer. It is, of course, a pertinent question whether Ford and Edison should have been permitted to amass huge personal fortunes in the process— people have a habit of looking askance at revolutionary leaders who emerge from a revolution with well-lined pockets— but that is not to deny the fact of their pragmatic radicalism. The instinct of the American people is purely practical. The) may cheer the man who says something, but they follow the man who does something. Until our radicals realize that nobody gives two hoots in an ash-can for their ideals, ideas or principles, but will be interested in anything solid they propose to accomplish, they won't get anywhere.

For the real thing that is wrong with our radicals is not that they don't know what they want, but that they don't know what they believe. The world is crying for a new religion, that is to say, a new purpose in life which will give meaning to everything and justify voluntary sacrifice. That is what the radicals lack. Each one is himself the evidence of what a real purpose will give to a man—faith and courage and determination—but as a whole they have nothing to offer a world which is hungry for something more than bread-and-butter and the biggest of mass-meetings.

We see the world hunting for that purpose everywhere: Japan seeking it in the Army and the sense of Japanese destiny, Russia seeking it in the dreary dogmas of Karl Marx and the homicidal hysterics of her Five-Year Plans, Italy and Germany seeking it in youthful shifted hordes and heroes, America not yet seeking it, but sinking slowly into a sea of meaningless statistics of money, wheat-crops, car-loadings, relief payments, and appropriations— statistics which are meaningless because we have no conscious national goal as we had in the World War.

That is what is really wrong with our radicals. They have been men crying in the wilderness, proclaiming nothing new or worth fighting or dying for, only the same old stuff: More money to this man. Less money to that! Crack down here, go easy there! Pass the bread-box instead of the hat and send the bill to the Mint!

Why? Why should we do all these things? Until the radicals can tell us that, until they can awaken in us a new sense of national destiny, a new sense of social values, a new individual purpose, they will be everlastingly wrong and will win no following in the nation they would like most of all to lead.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now