Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Yelverton case

EDMUND PEARSON

Major Yelverton was embarrassed, one day, when he received a message from a lady. Letters from ladies were no news to the Major, but there was a peremptory ring about this one which fussed him. She was a terrifying lady—to an officer in the Royal Artillery—her name was Victoria, and she added that she was "by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Queen, Defender of the Faith, and so forth."

She gave him her greeting, but went on, in a nasty, dictatorial manner, to say that Major Yelverton owed a man named Thelwall £259 (plus seventeen shillings, thrippence) for the board and keep of Mrs. Yelverton. The Queen went into details about these moneys, specifying a horse at £25; cash, £50; and other items, down to six weeks' washing at six shillings a week. She intimated to the Major that unless he paid Mr. Thelwall, unpleasant things would begin to happen.

The Major replied, and respectfully informed the Queen that somebody had been kidding her. The lady, to whom Mr. Thelwall had been supplying horses and cash and washing, was not and never had been Mrs. Yelverton. Her real name was Miss Theresa Longworth, and she was a bold, brazen person, of a kind he hardly cared to mention to the Queen at all. The actual Mrs. Yelverton had formerly been named Miss Emily Ashworth, and she was now at home, where she ought to be, taking care of their two infants—both of them perfectly lawful little Yelvertons.

The Major was pretty serious: he had already spent a few days in jail, charged with marrying Emily without getting rid of Theresa. But he knew well enough that Mr. Thelwall and the Queen were being dragged into this row by the very lovely, extremely determined, and thoroughly furious Miss Longworth. He, the Major, was now stationed in Ireland, and in that country it was possible to get him on the witness stand, when the indignant lady went to the mat on the subject of his philanderings.

Theresa had been pursued and courted by the rascally Major all over Europe; there had been petting-parties by land and sea; there had been two marriage ceremonies, and any amount of traipsing about together in hotels; together with enough love-letters to sink a ship. Who? cried Theresa, to the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland and a special Dublin jury—who was married, if she were not?

The gallantry of the Dublin men knew no bounds. Although the Major had been born in Ireland and Theresa in England, the crowd raised the roof cheering for her. Who could look at her, at her blonde hair, which, said the reporters, was "of that rich and glowing golden hue, in which Titian delighted to portray his ideal beauties"— who could see this, and not be on her side? Not the Dublin reporters!

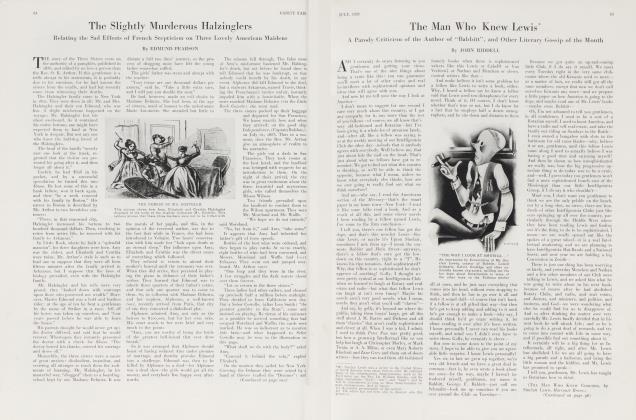

As to the Major, one needs only to glance at him (refer to illustration) to perceive that he was a Parlor Snake. Reporters were shocked to observe the coolness with which he gave his evidence, and "the revolting cynicism of his avowals which caused a thrill of horror to run through the Court."

When Theresa testified, her "sweet and musical voice, and exquisite propriety of diction" enhanced her attractions and convinced her listeners. She told the jury:

"My parents are dead. One of my sisters is Mme. Lefebvre; she lives in Boulogne. I was educated in a French convent, and brought up as a strict Roman Catholic. In 1852, when I was twenty, I had been visiting my sister in Boulogne. One evening, in the summer, I took the steamboat for London. My sister came to the pier to see me off, and it was arranged that I should travel with two ladies who were on board. They stayed on deck all night with me; it was a warm night and the sea was calm. The ship was full of passengers and we preferred to stay on deck.

"Before we sailed, my sister threw a shawl to me from the shore, and it was caught by a gentleman, who was with these two ladies. He put it round my shoulders, and was otherwise polite and attentive. This gentleman was Major—he was then Captain—Yelverton. He fetched his plaid from below, and we put it over our knees, as he sat opposite me in a chair. We arrived in London at daylight. The two ladies said goodbye; Major Yelverton got a cab for me, and then he went away—I do not know where. I went to visit the Marchioness de la Bel line, at whose house my other sister was staying. Next day, Major Yelverton called, and my sister and I received him. He had asked to call; I did not invite him."

But when the Major gave his version of that night, the trip up the Channel became a bit more clubby and sociable. In his story, the two chaperones do not appear at all; the plaid, he hinted, enfolded Theresa and himself; and their conversation dwelt upon the happy chance of their meeting, and upon sunset and evening star and similar topics.

After all, you know, Yelverton was Captain the Honourable, the son of a peer, and he would one day be Viscount Avonmore. His erect, military figure (figger, to him) was something to see. As for his Dundreary whiskers, young ladies of 1852 considered them maddening; the Queen herself had acknowledged the fascination of a slighter pair.

The Major's account ended with a difference. When, at last, a breeze of morning moved, and the Planet of Love was on high, they saw, with regret, the smoke of London town. They did not part at the wharf. He accepted Theresa's invitation; accompanied her to her friend's house; went in and stayed two hours. A room was offered him, where he might change his travelling clothes. This he did. Nothing else happened, but the incident, if true, implied a sort of camaraderie.

After the call of next day, as both parties agree, there came an interlude in the friendship. They parted for more than three years. Theresa was in Italy; Captain Yelverton stationed at Malta. The fires of love were fanned by a correspondence—a shoal of love-letters so vast, so tender, and so puzzling that, in later years, it took many barristers to disentangle their meaning. Some of these lawyers set up carriages and sent their sons to the universities on the proceeds.

Theresa, when she dipped her quill in the violet ink, looked toward the moon, and addressed her beloved, set a standard to which no girl today can aspire. Her harsh native tongue was inadequate, and she had frequent recourse to the languages of passion: French and Italian. Nor was the Major, that man of action, much less literate.

Continued on page 58

Continued from page 34

They passed from "My dear Miss Longworth" and "Ever your sincere friend, Wm. C. Yelverton" to "My dear Theresa". Then suddenly, at his request for less formality, he was addressed as "Carissimo Carlo mio", while he responded "Cara Theresa mia." Finally, the Major achieved "My dearest little Tooi-tooi" as a satisfactory salutation to his sweetheart. He varied this with "Tooi-tooi carissima". He described a dream in which Theresa appeared to him, and ended:

"You're a dearest darling darling small tooi-tooi, &c., &c., &c., . . . and 'da capo'. Addio. Sempre a te.

To reduce the cruel distance between Italy and Malta, and to bring the lovers together, the Powers of Europe took up the gage of battle. The Crimean War broke out, and Yelverton proceeded to Constantinople. So did Theresa, assisting the French nuns as a nurse. To the Galata Hospital came the Major, and finding Tooi-tooi utterly fascinating in her uniform, besought her to marry him. She declined to leave her suffering soldiers. He went away, but came back, love-sick and miserable. The war ended, but Theresa lingered in the Orient, visiting her friends, General and Lady Straubenzie. Thither came the melancholy Major, and he was received by everyone as Theresa's plighted lover.

Wandering, one day, by her side, he disclosed the tale of an aching heart: he had no income but his pay, he was in a financial pickle, and he had promised his family to marry no lady who could not pay his debts. About £3000 would do it, said he, with the love-light in his eyes.

Theresa replied tenderly that the engagement must be broken; she was entitled only to the interest on her money. Next day, the Major returned with a new idea: they would secretly be wed at the Greek Church at Balaclava. But, to the devout Theresa, there were no true priests but the Catholic, and no true Catholics but the Roman. She declined again.

Now, Major Yelverton, as he stood in the Dublin court, was* in a frightful jam. He might admit that sometime, in his pursuit of Theresa, he had been animated by the feelings of a true lover, an officer and a gentleman. If he did so, it would lead to the conclusion that his purposes were sort of half-way decent, and therefore that, perhaps, he really had ventured into matrimony. This would naturally lead him. straight to jail, as the bigamous husband of Miss Ashworth. Or else he had to paint himself as a scoundrelly seducer, into whose head never entered the tiniest bit of honorable intention. And then, his trouble would be to escape being dissected by the infuriated populace of Dublin.

"Do you mean to say, Sir," inquired Mr. Sullivan, Q. C., sinking his voice to a scandalized whisper, "do you actually mean to say that it was your intention to make this lady your—your—"

Mr. Sullivan glanced apologetically at the Lord Chief Justice, then looked down at the floor and hid his face with a bunch of papers:

"Your—mistress!"

"I do, Sir," replied the abominable Yelverton.

Two or three lawyers shrieked aloud, and had to be revived with smelling salts, and when the Major returned to his hotel that night, two squads of constables were needed, to protect him from a committee of gentlemen who had sworn to pluck out each hair from his whiskers, one by one, and then throw him in the river.

But he went on to worse things. He swore that the whole Crimean adventure was a relentless pursuit, of which he was the bedeviled victim. Theresa, said he, was always throwing herself at him, and, as a result, "great familiarities" took place. The Lord Chief Justice faintly remarked that this was distasteful, revolting and hideous, but that they must have particulars.

When Theresa left Constantinople on a steamboat, the Major was there. Another nocturne at sea—and the Major began to describe it. Barristers and jurors leaped to their feet to remind my Lord that there were ladies in Court. The Chief Justice uttered a warning and a few ladies withdrew. He then said that if others chose to remain, he "could not help them". They would be contaminated beyond repair. After a few more appeals, the Court was, little by little, cleared of ladies. The Major then admitted sitting on deck, with his arm around Theresa's waist; apparently he tried to snap her garter, but the scene was interrupted by some sailors who came on deck, while the reporting of it was checked by the swooning away of every newspaper man in Court. All the historians resort, at this point, to asterisks.

Continued on page 59

Continued from page 58

The lovers returned to England, and when the Major was ordered to Leith, Theresa turned up, with her friend Miss MacFarlane, at the nearby city of Edinburgh. He attended her every day; they rode together, and went to social functions as an affianced pair. The Major's first thought of a Greek marriage was now followed by the suggestion of a Scottish one. Any kind of wedding, so long as it was a little bit phony, seemed acceptable to him.

"One day," said Theresa, "he took the prayer-hook from the table, and I went to his side, and he read the marriage ceremony, and said 'That makes you my wife by the laws of Scotland.' I opened the door of the room in which Miss MacFarlane was sitting, and said to her: 'We've married each other.'"

After this, the Major, having assumed as few as possible of the responsibilities of a husband, claimed all the privileges. Theresa refused, and demanded a marriage according to the rites of her own Church. When the Major persisted that she now live with him, she discreetly fled from Scotland.

The Honourable the Major's story of the Edinburgh episode was that there was no prayer-book, and no reading of the service. Instead, he persevered in his hellish designs, and accomplished them one day, "on the sofa in Mrs. Gamble's sitting room." The auditors, in Court, burst into boos and hisses, and the Dublin gentlemen announced their intention of drinking the Major's blood, hot, in the market-place.

Some weeks after the flight from Scotland, so the lady testified, the Major invited her to join him in Ireland for a marriage before a Roman Catholic priest. They were never stay-athomes, but were always eager to see what a new country might do for them. Yelverton went on leave, and the two met at Waterford in Ireland. There was a search for a priest, and for two weeks Theresa and the Major travelled around Ireland.

As Mr. Roughead, the only modern historian of the case, delicately puts it:

"They engaged, in the various hotels which they visited, a sitting-room, a bed-room, and dressing-room which contained a bed, so there is no architectural reason for rejecting the lady's statement that until the religious ceremony was performed they occupied separate rooms. On the other hand, the moral probabilities are in favor of the Major's contrary assertion; and the pair were naturally regarded by the hotel witnesses as married persons."

On August 15, 1857, in the chapel at Rostrevor, Theresa and the Major knelt together at the altar and the ceremony was performed. There was some question as to the Major's religion, but Father Mooney was satisfied as to that. The Major's version of this did not differ greatly from Theresa's. He admitted that they knelt before the priest, who read "a portion of a marriage service."

They travelled together and parted, and did this more than once in the next year. They were in France together for three months, registering everywhere as Mr. and Mrs. Yelverton. Theresa's passport was in that name.

Next summer, leaving Theresa in France, the Major went to Edinburgh. Here he found the £3000 which his family's honour required. It was inextricably attached to the person of Miss Emily Ashworth. He married her, and, it is good to record, was promptly clapped into jail for bigamy. His defence, at the trial in Dublin, was that the Scottish marriage never happened; and that the Irish one was illegal, since he was not a Roman Catholic.

The jury found the defence to he a miserable subterfuge; both marriages, they said, were valid. The crowd took Theresa's horses out of her carriage and drew her, in triumph, to her hotel. Everyone, including the committee of gentlemen, got so illuminated that Yelverton, the serpent, wriggled out of town with his life.

He squirmed over to Edinburgh, and laid his case before a Scottish judge. This old gentleman was not allowed to see Theresa's golden hair, and so he gave a decision against her. There was another appeal, and three more judges divided 2 to 1 in her favor. The Major now raised the money (from Emily, I suppose) to take the case to the House of Lords, and their Committee voted 3 to 2 for Yelverton. Thus, by the margin of one judge, Emily and not Theresa was finally established as Mrs. Yelverton, and later as Viscountess Avonmore.

The Army had already thrown out the noble lord, and England, generally, seemed to hope he would choke. When, in 1883, he died at Biarritz, he was an obscure person.

Theresa travelled far and wide, lectured and wrote books. Novels were written about her romantic life. She came to New York, and had a talk with Horace Greeley in the old Hotel Albemarle. He and his Tribune warmly supported her cause, and denounced the Major. Theresa's lectures, in America, were not successful, but she wrote a book about us, and also a novel, of which the scene is the Yosemite. My devotion to her memory has caused me to try to read it.

To the end, she remained strikingly beautiful, spirited in mind and body, but saddened and lonely. She died in South Africa, before the Major. It had been her fate to expend her energy fighting to prove that she was the wife of a man whom the late Brander Matthews once described to me as "a singularly perfect specimen of the skunk."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now