Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

George Jean Nathan

■ WHITHER?—Among my minor prejudices is the word whither in the title of a hook, play, lecture or magazine article. Anything labelled "Whither America?", "Whither Are We Drifting?" or whither anything else finds in me a very reluctant customer. There is something in whither that evokes the picture of a sententious stuffed shirt who, given in private person to the use of where, imagines that the employment in his public manifestations of the tonier whither will invest him with a bit of gravity and literary air. Having so apologized for the title of the present inquiry, I duly pain my clients with the query: whither is the stage going in the matter of sex?

That word sex, incidentally, is something else that—with its touch of evasive hypocrisy—is beginning to wherret me. In private speech, of course, none of us, including myself, is guilty of the polite circumlocution which it represents. While it is impossible in this particular public place to state the synonym or synonyms which we are accustomed to use in its stead, such franker and more direct locutions hardly need identification. Yet with the exception of maybe a couple of young sub-Mason and Dixon novelists, one expatriated Irishman, one (deceased) expatriated Englishman, and a few bad boys from Chicago— most of them at one time or another suppressed—there is scarcely a living writer in English who does not take refuge in the ambiguous term. I Even the late Frank Harris, who was certainly no linguistic chicken-heart. had timid recourse to it to designate everything from Kamasutran calisthenics to the duct of Müller.)

Having thus apologized doubly, I restate the query: whither is the stage going in the matter of sex?, and proceed to business.

It is plainly evident that, save in a few sporadic instances, the play that deals seriously with sex in the normal aspect of the past is no longer successful in capturing the interest of audiences. The reason doubtless lies in the fact that, while the audiences are not necessarily themselves abnormal, they have wearied of the years-old dramatic reiteration of normal sex themes, and have demanded a change, if only for an evening's theatrical diversion. The Captive began to indicate the altered taste; and since then the statistician of the theatre has noted a steadily increasing dramatic drift toward sexual bizarrerie. So decided a drift, indeed, that one wonders what will be the end. Certainly when America's first dramatist is loudly ridiculed for attempting, in his latest play, to fashion drama out of a married man's distress induced by the fact that he has been unfaithful on one occasion to his wife; certainly when one of the foremost of our actresses is bustled off to the storehouse after only a few nights for playing the role of a woman who almost dies from shock when she learns that her husband has been carrying on with her maid; certainly when, with a single exception, every last play treating soberly of normal sex reactions during the same just-ended theatrical year has been a box-office failure— certainly then it becomes obvious that the wind is blowing the drama's whiskers in a new and strange direction. (Or, perhaps, simply in the old, classical one.)

The wind in point has accordingly and successfully wafted a number of peculiarly exotic blooms to us in the last few seasons. It has wafted Mourning Becomes Electro, with its undertone of incest; Design For Living, with its overtone of androgynous sex; The Green Bay Tree, with its male perversion; Dangerous Corner, with its note of homosexuality; Tobacco Road, with its combined erotomania, incest, nymphomania and what not else; Mademoiselle, with its hardly concealed suggestion of tribadism linked with paedophilia; For Services Rendered, with its incidental note of combined algolagnia, bipolarity, conversion and paralogy; etc., etc. If things keep going in the same direction, and with the same velocity, the sex drama of the next few years will make the Vatermord of Berlin notoriety look in comparison and retrospect like A Kiss For Cinderella.

ANTI-NAZI DRAMA.— A second reflection on the season just concluded brings us to the demulcent conviction that we have now probably had all the anti-Nazi plays that we are going to get, and that next season will be mercifully free from evenings in which German Jewish households (whose large nobility and unexampled virtue are indicated by an unremitting series of paternal, maternal and filial osculations and embraces) are suddenly disturbed by the entrance of a doggy actor in a brown blouse who looks disconcertingly like Mr. Eric Von Stroheim and who— after several stertorous and somewhat salivary pronouncements to the effect that the aforesaid Jewish families are vermin, swine, lice, scum, offal, dung, and various foul smells—thwacks the son across the face with his swagger stick, kicks the old father under tin* library table (usually piled with Goethe, Schiller, Lessing and Vicki Baum by way of implying the old man's subversive cultural leanings), denounces the old mother as a female Schnauzer of Jewish extraction, and—after a lascivious glance through his monocle at the blonde Aryan serving-maid—loudly commands that the entire lot, with the exception of the blonde, be out of the country within five minutes, thereupon stamping out of the house followed by several supers from the local Y.M.H.A. with swastikas on their arms.

OUTSTANDING PERFORMANCES OF THE SEASON

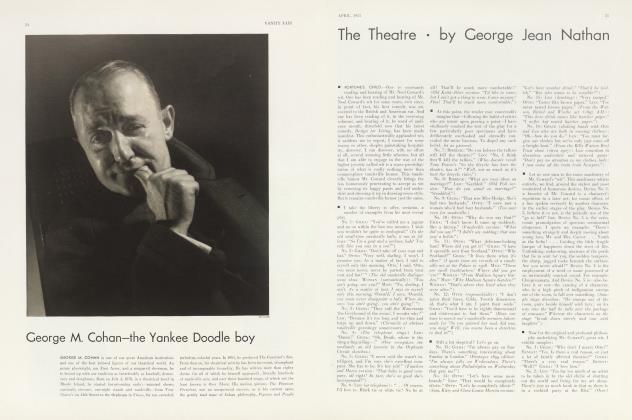

George M. Cohan in "Ah, Wilderness!"

Henry Hull in "Tobacco Road"

Dennis King in "Richard of Bordeaux"

Walter Huston in "Dodsworth"

James Dale in "The Green Bay Tree"

Frank Lawton in "The Wind and the Rain"

Philip Merivale in "Mary of Scotland"

(Note: No women's performances seem to the present critic to have approached the quality of these men's perform-

OUTSTANDING

ENSEMBLE

PERFORMANCE

The company presenting ' Her Master's Voice"

OUTSTANDING MUSICAL SHOW PERFORMANCE

Clifton Webb in "As Thousands Cheer"

OUTSTANDING DIRECTORS OF THE SEASON

Jed Harris with "The Green Bay Tree"

Howard Lindsay with "She Loves Me Not"

The four anti-Nazi plays disclosed during the season (one of them, Races, produced by the Theatre Guild, was gratefully allowed to pass out in Philadelphia before adding to the New York agony) all pursued, with but minor deviation, the standard pattern. What other pattern, indeed there might be for such plays is pretty hard to figure out. The father may, true enough, be a goy married to a Jewess, as in The Shattered Lamp, or the ingenue may be a Jewess betrothed to a Gentile stormtrooper, as in Birthright, or everybody may be Jews, as—if memory serves—in Kultur, but, whatever they are, Eric Von Stroheim, with his swagger slick, monocle and swastika is dead certain to pop in at the end of the second act and do his stuff, to the accompaniment of considerable sympathetic window-pane busting and off-stage general hell-raising on the part of presumably Nazi stagehands. After a (Continued on following page) dose or two of this routine mallarkey, it may be appreciated that any additional Nazi opera are hardly likely to offer much interest or stimulation, whether in one way or another. About the only possible novelty would be to show a Berlin Jewish household with Maxie Baer, Maxie Rosenbloom and Jack Dempsey (by his own confession partly Jewish) occupying the guest rooms and to have them come downstairs in their pajamas on the entrance of the inevitable Eric and knock his block off. This, if followed by an exhibition of fancy bag-punching, might conceivably sell a few tickets at the box-office, which would be an added novelty.

A more serious thought that occurs in connection with these theatrical anti-Nazi propaganda exhibits is that, instead of accomplishing their aim in creating sympathy for the persecuted Jews, they actually—and refractorily—often provoke in their spectators, if not exactly sympathy for, at least a trace of generous understanding of, the Nazi point of view. It is a well known dramatic fact that the moment you make a character or characters too all-fired noble and sweet an audience will gag at them. And, as a consequence of the long local display of a run of sickening Pollyanna drama, with its emphasis on sweetness and light, it is equally a well recalled fact that there followed —to audiences' great satisfaction—a kind of drama in which the villains of the antecedent drama were, for all their knavery, pictured fairly and honestly as being possessed of certain facets of dignity, equity, and even lovableness.

The principal trouble with the anti-Hitler propaganda drama seems to be that it makes all its Jews Pollyannas and all its Nazis Simon Legrees, with the result that audiences (even when largely Jewish) are nauseated by the goose-grease and are brought quietly to allow to themselves that the Nazis cannot, after all, be quite so bad as the playwrights paint them. If dramatists wish to manufacture anti-Nazi plays that will accomplish their propaganda ends, it might be well for them to ponder the reactions to the plays that have been revealed thus far. This current Hitler sardoodledom will never get them anywhere. Surely not all the quiet, intelligent, studious, old family-loving Germans are Jews; there must also be at least a few such in the Nazi ranks. And surely not every German, young or old, who believes in Hitlerism is a Jack-the-Ripper. Let the playwrights show the other side as well—and then may the best team win!

■ REFLECTION NO. 3.—A third reflection on the past season has to do with the melancholy failure of our American socalled experimental dramatists at their own game. It would seem to the theatrical commentator that the chief weakness of these experimental playwrights is that what they are pleased to consider more or less daring and novel experiment is, if not quite as old as the hills, at least old enough to be thoroughly familiar to even the more casual theatregoer. One often wonders, incidentally, if these gifted boys have ever taken the trouble to go to the theatre during the last ten years, in a general sort of way, to learn what is going on there.

■ Consider, for example, by the record of this last season alone, the case of O'Neill, grantedly the first among the local experimental playwrights. In Days Without End he presented what he imagined were two instances of fresh experiment, to wit, the use of a masked second character to indicate the other self of his first character, and the device of a story in the process of being written by the protagonist and closely identified with the latter's immediate overt acts, thoughts, fears and resolves. The first experiment has been familiar to theatregoers for more than a decade, since initially it was employed by Alice Gerstenberg in Overtones', and the second experiment has been even better known to them for an even greater length of time through its use by Wilhelm Von Scholz in the Theatre Guild's production of The Race With the Shadow, to say nothing of various manoeuverings by Molnar, Schnitzler, et al. (Speaking of O'Neill, though it has nothing to do with the present case, it is odd to recall that the selfsame critics who decried him for turning dramatically from atheism to faith in Days Without End praised him enthusiastically for turning from cynicism to sentiment in Ah, Wilderness!)

Consider, secondly, John Howard Lawson, who likes to believe himself such an experimenter as hasn't been heard of in the world since Darius Green fastened a pin-wheel to his proboscis, tied a bedsheet to his tail, and jumped off the barn in the sublime faith that he was a flying machine. Mr. Lawson's most recent great experimentation consisted—in The Pure In Heart— in bringing "a new mood into the realistic theatre", the aforesaid new mood being negotiated by putting some modernistic scenery on a revolving stage, chopping his acts into short scenes, causing off-stage music to be played through certain episodes, and at points in the proceedings introducing a blues singer and six Albertina Rasch dancers. With infinitely greater art and infinitely greater success, and with about twenty times as much originality and inventiveness, any number of musical show producers the world over have been doing exactly the same thing for years—and with very much better basic dramatic stories, to boot.

Consider, finally, Sidney Howard and his much-admired experimental staging technique in the case of Yellow Jack. If, either in the way of setting, lighting, or general staging, this was a new and novel experimental technique, Herr Leopold Jessner will, when and if he hears about it, be the most surprised man in or out of Germany. (Additional reviews by Mr. Nathan will be found on page 72b.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now