Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe care and feeding of murderers

EDMUND PEARSON

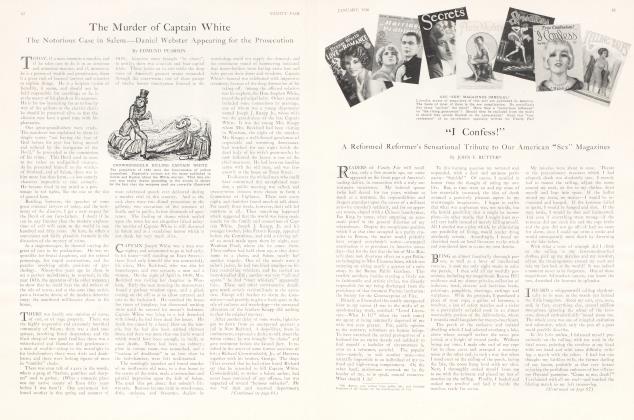

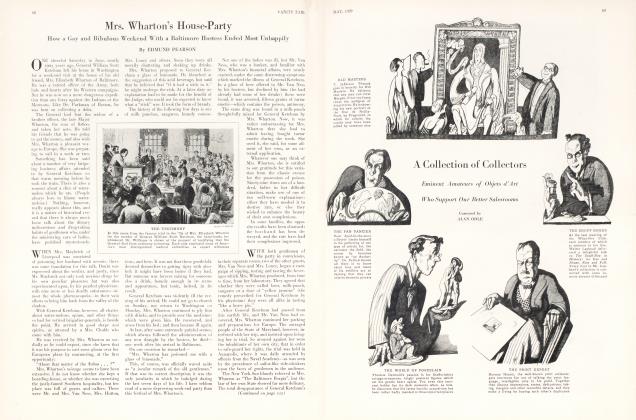

The illustration on this page sets a new record in American chuckle-headedness. To all who ask for one reason why America has ten times her fair share of violent crime —murder and robbery under arms—the answer is:

"Look here, upon this picture. . .

The faces of this delightful trio are receding from public memory. A few weeks ago they were on all moving-picture screens. They are not, as you might suppose, just two old college pals and their sweetie. The one in shirt-sleeves is John Dillinger—at the moment this photograph was taken, a prisoner of the law' in Indiana for robbing banks and committing an indefinite number of murders. He and his gang had left at least four dead bodies behind them; the bodies of men who had foolishly tried to protect the property which Mr. Dillinger was carrying away.

The person in the centre is Lawyer Estill, one of Indiana's county prosecutors. He represents the People; is the guardian of law and order. At the moment he stood here, with arms lovingly entwined with Murderer Dillinger's, it was his imminent duty to prosecute the outlaw and demand the death penalty. But—it's always fair weather, when good fellow's get together, and there was no personal animosity in Prosecutor Estill's heart. Rather, the motto of many others toward our bandits and murderers: give the boy a break!

The lady is Sheriff Lillian Holley, custodian of the jail. She had come into this office for a reason which seems good to many American electorates: her husband had held it before her. Although Dillinger was a notorious jail-breaker, boasting of his intention to escape, he was given privileges. He roamed about the prison and amused himself with pocket knives and razor blades. He was visited by his moll, who talked with him by secret signals. When he whittled out a mock pistol, held up twenty or thirty men, herded them into cells, and drove away in the sheriff's car, he took with him one or two machine guns and another murderer, named Youngblood.

The subsequent shooting of Youngblood cost at least one officer his life. How many more people will be murdered as a result of the camaraderie indicated in this picture, it is too early to guess, but I trust that the ghosts of the dead will give Prosecutor Estill and Sheriff Lillian a restless night or two, and an occasional bad dream.

Creatures like Dillinger are as much out of place among human beings as rattlesnakes in a nursery. The casual, light-hearted manner toward them is not confined to Indiana, nor to slightly shallow persons like Sheriff Lillian. We can invent endless excuses for murder. A number of our alienists and psychologists hold that the murderer who commits his crime with extreme ferocity should tenderly be preserved, so that he may be exhibited to other psychologists, as orchids are shown in a conservatory.

But, it is argued, on the other hand, that if the murderer butchers his victim politely, and with regard to etiquette, he should certainly be saved from the rude hands of the executioner.

For example, a man named Bull was lately under the death sentence in Massachusetts. Senator Copeland, chairman of a special committee investigating crime, and his chief agent, Colonel Franklin S. Hutchinson, were both interested in the fate of Bull.

The arguments used by Colonel Hutchinson, as reported by the Associated Press, constitute a priceless illustration of popular naivete.

Bull, said the Colonel, was a "young intellectual" who used to give "seances" in fashionable New York hotels. (The nature of the seances does not appear.) During the hard times of last summer, Mr. Bull went to Greenfield, Mass., bought a revolver, and held up a filling-station.

"Apparently," said the gallant Colonel, "there was nothing vicious in his conduct while attempting to rob the station."

I wish wTe could have the Colonel's definition of "vicious". The usual procedure in hold-ups is to jam the muzzle of the gun into the victim's stomach, and growl "Stick 'em up!" Bull seems to have been less crude. It must have been gratifying for the owner of the filling-station, to notice that his despoiler did not jostle, nor, in his conversation, split any infinitives.

• What happened next—the Colonel is a bit sketchy here—was that somebody called a policeman, who was promptly shot dead by the "young intellectual". I think I detect in Colonel Hutchinson's narrative that slight distaste for the murdered man, which is customary in those humanitarians whose hearts perpetually bleed for the murderer. But the Colonel ended with the remark:

"I don't think he should be executed for a technical murder, for that is what it was."

In spite of this nice distinction, I learn that the physicians were unable to recall the dead man to life by telling him that he was only technically murdered. It was, however, a great consolation to the family of the slaughtered policeman when they found that their husband and father was only technically dead. He might have been brutally plugged in the guts by a rough gunman, instead of delicately drilled in the abdomen by an intellectual.

Murder has long been one of our major sports. Recently, it has grown into a national industry. There has always been a crime wave breaking over our country, for a hundred years and more. Our foul record for the killing of human beings is an old one. The murders for revenge, the crimes passionnels, have always been committed here, as in other countries. The threat of punishment is everywhere feeble to check murders of this variety. But our evil eminence is for ruthless slayings by robbers and gunmen, and for the sudden emergence of the combined kidnapper and murderer. W'e could wipe out this disgrace in two months—if we really cared to do so. The death penalty—not its mere existence on the statute books, but its use—would discourage the future Dillingers and the organized kidnappers, over-night. Do not believe any "criminologists" or alienists, or distinguished prison-wardens, when they say that the death penalty, where enforced, does not make the potential murderer stop and think. These learned men are talking nonsense: the object lesson of Canada is too clear. Our murderers do not cross our northern border, and they well know why they do not.

(Continued on page 70)

(Continued from page 44)

It should be remembered that in New York State, for example, the death penalty, in a scientific sense, is not being tried. To execute 2% or 3% of the murderers is not a test.

The outbreak of brutal kidnappings during last summer was followed by a few convictions and prison sentences. One kidnapper, McGee, was condemned to death. He expressed astonishment: all that he had done was to capture the daughter of the City Manager of Kansas City; keep her chained to a wall in a filthy cellar which had been used as a hen-roost; and extort $30,000 ransom.

Such an incident is soon forgotten. Nobody will recall it when, presently, McGee will be making his "brave fight for freedom." Then the word will be: give the boy a break!

To cause any horror at all, a murderer has to hack his victim to pieces by slow degrees. Does that startle anyone? The answer comes as I write: a family have been receiving telephone messages from kidnappers who had captured their father. Send the money, said the speaker over the telephone, or we will send him home a fragment at a time. In the end, however, they merely tortured him; beat him up; knocked him on the head, and left his body on a dump. Merely a technical murder. And it attracted enough attention to rate page three of the news.

As soon as McGee was sentenced to death, the newspapers expressed satisfaction, and the Attorney General issued a congratulatory statement. Kidnapping had been "halted." But McGee is still alive, and the kidnappings go on. The successful Bremer job was one which showed how well criminals know that our law is either weak or frivolous. The kidnapping and murder of Brook Hart, in California, was followed by a savage lynching— one of the results of public belief that the law is breaking down.

The causes of all this lie deep in our national character, and they are ineradicable. We can all see—even the "liberal" writers can see—the evil character of the lawyer who devotes himself to teaching millionaires how to cheat justice. But these people admire the lawyers whose life work is to cheat justice by setting murderers at liberty.

Will we make criminal lawyers adopt standards of common decency? Will we prefer an orderly and systematic penology to the sentimentalism of the Dillinger case on one hand, or the lynching mob of San Jose on the other? And is there any hope that we may reduce the number of people who, in one way or another, are making the murderer our best-protected citizen?

The answer is: not a chance.

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now