Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFirst flight

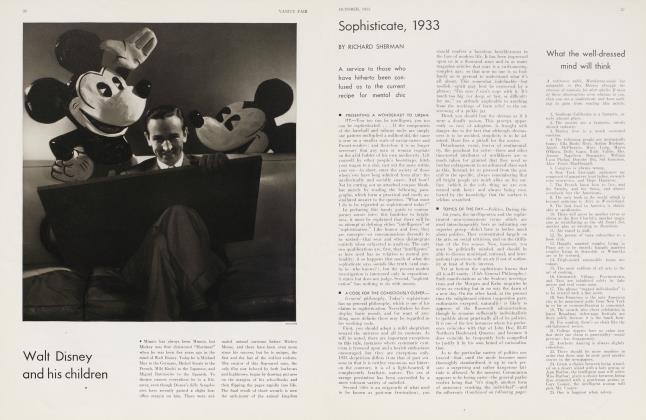

RICHARD SHERMAN

She had been walking all afternoon, walking for blocks and blocks very rapidly alone, and it was almost dark when she came home. Sister was lying down— she always rested for an hour before she gave a big dinner, and then drank a glass of hot milk before her bath—and Bill was in the library reading the paper with a mounded pile of cigarette stubs on the table beside him. He was dressed already, a chubby, ruddy man whose shiny shirt-front bulged and whose collar cut into the folds of his neck.

"Hello, kid," he said.-

"Hello." -.

"Been out? Bridge?—"

"No," she said. "Just walking. It's wonderful—warm, and sort of misty, like spring."

"It is spring, almost," he answered. "Better get dressed. Your sister wants you to look pretty, you know." Sister was God to Bill: she'd been making him jump through hoops, and making him like it, ever since their marriage.

"Bill—" and then she stopped. She didn't want to talk to him about it. He couldn't help her, oidy Sister could do that. Sister was her flesh and blood, Sister would know what she should do.

"What's on your mind, kid?" he asked. He wasn't as stupid as most people thought. She did wish, though, that he wouldn't always call her "kid." After all, she was seventeen.

"Oh—nothing."

"Hate to go back to school? Is that it?" "No."

He made a gesture toward his wallet pocket. "If you're broke, you know. . . ." but she shook her head. "No, thanks." He and Sister gave her everything. When Mother died they had taken her in. they were sending her to Miss Porter's, they had parties for her when she came home for week-ends like this one. They were wonderful to her. But. . . .

"Well." She turned to go. "I guess I'll get ready."

"Sure," he said, and then added, as she was at the door, "Martha says someone's been calling you; wouldn't leave his name. It's probably one of your boy friends."

She didn't even look back at him, but only said, "Yes, 1 know" and left the room.

He shouldn't have called. She had said she'd let him know sometime this evening; he wasn't to call her.

There was a light under Sister's door, and she knocked: Sister insisted that they always knock—"It gives each o^ us some sense of privacy and independence, don't you think?"

"Come."

The room was full of Sister's particular kind of beauty—a feminine disarray of flowers and tissue paper and mules and silk underthings, and that strange perfume heavy in the warm air. Sister was sitting in a boudoir chair, drinking her milk, while Gretchen did her feet.

"Hello, darling," she said, closing the magazine that lay in her lap. "You'd better be getting dressed, hadn't you?"

She sat down on a chaise-longue and watched Gretchen deftly manipulate the red-tipped toes.

"Sister, remember that man we met at the Bronsons' about a month ago?"

"What man, sweet?" Sister lighted a cigarette and blew a cloud of smoke into her empty glass. "Young Johnny Leavitt?"

"No, the one—the one who used to be married to Flora Angel."

"Oh, Ralph Angel. Yes, of course. I'd met him once before someplace. At some night club. He dances there, I believe. At the, the—"

"The Club Dore."

"Oh, and you saw him again when the Elliots took you there? How nice, He's fascinating, they say; a combination of gangster and gigolo. Flora was crazy about him, only of course she was a fool to marry him.—Gretchen, please!" She jerked her foot away. "That's enough anyway, Gretchen. Get my bath ready, will you? And remember, not too hot."

Gretchen scrambled awkwardly from the floor, gathering the little instruments into a handkerchief. She marched stolidly toward the connecting bath, and in a moment there was a sound of rushing water. Sister had risen and was peering anxiously into her dressing-table mirror.

"I look a fright," she said. "My tan's all gone, every bit of it. What's the use of going south every winter if you can't keep a tan anyway?" She stood erect again, and stretched her long slim arms straight above her head, and yawned. "I'm dead." she said, "and with twenty coming for dinner. Oh, well. . . ."

"Sister, that man, the one I was talking about, that Ralph Angel—"

"Gretchen!—Excuse me, darling." The bathroom door opened. "Gretchen, where's my nail buffer?"

"In the drawer, Mrs. Colt." Gretchen retreated, leaving them alone. Sister's back was bent over the dressing table. "There's no order around here," she said. "Confusion, everything's confusion. What were you saying, dear? Really, I think you'd better be getting dressed. They'll all be late, of course, but still we can't run any risks."

"Sister, when a man is older than you are—

Sister turned swiftly. "Darling]" she said. "You haven't gone and fallen in love with anyone, have you?"

"I don't know. I want to know what it's like, being in love. Ralph Angel—"

"Ralph Angel?" Sister began to laugh, relievedly. "Oh, I thought you were serious. I thought you'd really met someone." She put on her worried face again, looking at herself in the mirror and talking over her shoulder. "You're such a child." And she sighed.

"I'm seventeen. Eighteen, really—next month."

The bathroom door opened, and Gretchen's head appeared against a background of steam. Sister looked at the clock. "Heavens," she said, "it's nearly seven."With one swift movement she slipped out of her negligee and into a towel robe. Then she turned. "I don't mean to sound rude, darling," she said, "but you're so young and so-—so.silly. Now run along like a nice girl and get dressed. You're much too young to be thinking about men. Especially,"—she laughed again—"Ralph Angel. Here." She put forth her cheek to be kissed: it was cool and soft. "Now hurry, dear. You know Bill doesn't like you to be late." Then she shut the bathroom door behind her, closing it noiselessly and efficiently.

The room was very still, but there was a pulse of the city outside and a pulse at the base of her throat. . . .

Well, perhaps she shouldn't have expected anything else. After all, Sister couldn't understand everything, and she was busy, and she had her own troubles. But—but she shouldn't have called her just a child; because she didn't feel like a child any more. He realized that. He was the only one of them all who understood that she was—was different now.

Gretchen came through the other door. "There's a call for you. Miss," she said. "Will you take it here?"

The faint roar of the shower started then, and that meant another three minutes till Sister came back.

"Yes, thanks."

She waited until Gretchen disappeared before lifting up the instrument.

"Hello," she said, and stood rigid waiting for that voice which, when it came, shot through her entire body.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now