Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBut we never win the Davis Cup

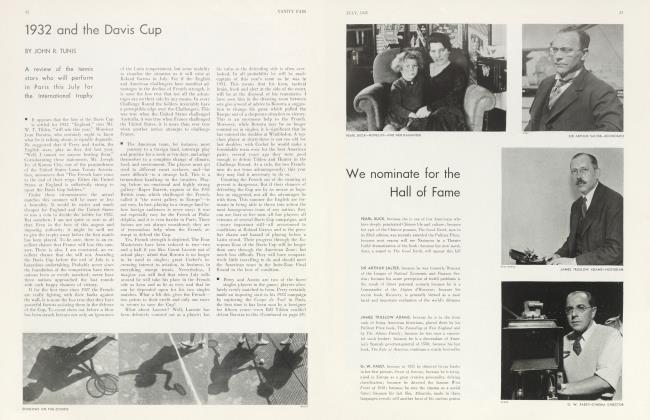

JOHN R. TUNIS

American tennis teams, with their high-pressure training and elaborate supervision, lose to the easy-going French

We gather our best tennis players together. We choose a team, train them carefully, coach them assiduously, pick a responsible leader and send them abroad under his direction. There we sweep the field at Wimbledon, and reach the Challenge Round in Paris in a burst of glory. But we never win the Davis Cup!

Why? Because the French have a stronger team. That ought to be the answer, but it is not an answer that will satisfy anyone who has seen a Challenge Round since 1928. For the fact is that the French haven't a stronger team; nor have they had one since the retirement of René Lacoste.

There was a period when the defending side with Cochet, Lacoste and Borotra was definitely stronger than the challenging Americans. That was in 1928; on our own team were Tilden, Hunter and Hennessey, the first past his peak, the other two just short of international class. Then Lacoste dropped out of the game. Since then the French, weakened by the loss of their finest singles specialist, have been inferior each year to the challenging nation. Moreover they have been growing progressively weaker, whereas we have been getting stronger, each summer throwing fine young players into the field: Lott, Allison and Van Ryn in 1930, Wood, the champion of Wimbledon in 1931. Vines, the best singles player in the world in 1932. Last summer, with five years added to their ages, the same team that won the Cup in 1927—minus their best man, Lacoste—was good enough to hold it!

Put it another way. Tennis is a game of youth, a game in which speed, footwork, quick reflexes and condition count more than in almost any other sport. Last July at Roland Garros Field, the average age of the American team was 23. The average age of the French was 34. The defending side gave away a handicap of 11 years per man. Yet France still holds the Davis Cup.

The reason why the French, with a vastly inferior team, have been victorious, why at present, with only two veterans on the eve of retiring, they have an excellent chance of doing so again, are, briefly, two. Rather do they come under two headings. First, the Davis Cup Regulations which give advantages to the defending nation with no changes of diet, climate, ball, and court surface to overcome. Second. American leadership, under which may be included the training and handling of our team in Europe, and the disposition of our players in the Challenge Round.

The first problem is something over which we have no control, although there is now an agitation in France to have the regulations changed so that the holder of the Davis Cup plays through the event like other nations. This is today the only great tennis competition anywhere in the world in which the winner of the previous year stands out. France sits back while other nations kill each other off in a terrific struggle for the right to be challenger. When the last round arrives the challenging team is invariably tired and jaded; the French are always comparatively fresh.

The yearly campaign for the Davis Cup is too long and too strenuous. In 1903 there were two nations competing: the United States and England. This summer there are thirty-four a record number. If the list has grown, the quality of the entrants has risen also. Ten years ago there were only two nations with players of real class: this country and Australia. England was in a slump. France had yet to surge to the front. With the spread of the game, however, has come an amazing increase in playing skill among various countries; today there are at least four nations with almost equal chances of victory and three or four but little behind. Between France, England, Australia and the United States, there is not a great deal to choose. Japan, Germany and South Africa have less balanced but powerful teams, while Italy or Czechoslovakia playing on their own courts might defeat any of the above named three. Besides this strenuous campaign which starts the first week of May and ends the first week of August, there is the exhausting fortnight late in June of the Wimbledon Championships in London. Seldom have the Americans done themselves justice when they plaved in Paris two weeks after this tournament, yet although Mr. Samuel Hardy, the captain of the 1931 team, on his return recommended that our players be not sent to England, they were there last June and are likely to be there this year. The call of the gate is strong.

A football season lasts two months and rarely includes more than eight games, in none of which do all the players stay through the entire contest. The Davis Cup season takes three months, and, with Wimbledon included our team is asked to compete in twenty to thirty matches within a space of twelve weeks. When you consider the nervous exhaustion of a five-set Davis Cup contest, and that some of the team may have to play three such matches on successive days, you can readily understand why they often reach the Challenge Round physically and mentally below par.

If the length, the severity of the campaign, and the natural disadvantages of playing away from home are the principal reasons for our failure to win the Davis Cup. American leadership has not always been so intelligent as it might have been. Our captains are well chosen, invariably former players, always charming men who make a great personal sacrifice of time and money to go abroad with the team. Captaining a Davis Cup team is lots of work and painfully little fun. But the fact is that every summer the same mistakes are made, every summer the same result: we fail to capitalize on the strength at our command and are outwitted by the enemy forces.

If an older captain is a necessity for a Davis Cup team, and I have yet to be convinced that he is, his function ought to be to supervise the living and training of the men in a sane manner. Yet while the French, a week before the Challenge Round, go out to Versailles where they rest quietly, coming into town only for a few hours' practice each afternoon, the Americans usually elect to live at a Grand Palace Hotel in the heart of the city. You can understand why the French come onto court keen and fit and we do not.

If this is not plain, let me describe the different training methods pursued. Directly after the punishing fortnight at Wimbledon one would imagine the Americans would limit their actual practice to just enough tennis to keep them in good physical condition. Not at all. They go after each other, hammer and tongs, hour after hour, day after day. Martin Plaa. the professional who coaches the French, was watching Allison play a singles match against Vines on the center court in Paris one afternoon last summer.

"Practice. Bon Dieu . . . that's not practice. Allison playing Vines ... a type he has played fifty, a hundred times . . . whose game lie knows perfectly. Ah, non, c'est un entraînement complètement idiot. Now there . . . that's what I call practice. . . ." And he pointed to where the canny Lacoste was feeding lobs to Borotra and Borotra was smashing, smashing, smashing from all parts of the court. This continued for ten minutes, then for twenty minutes the Basque would hit a deep forehand drive to the corners and rush the net. Do you wonder Vines lost when they met three days afterward? The French always practice this way, so have all the great players of former times that I have ever seen; Suzanne Lenglen, Tony Wilding, Bill Tilden. for example. One reason why we have a number of first class players but no Tony Wildings or Bill Tildens in American tennis today is on account of the manner in which they practice.

The captains ought to direct the practice wisely. The captains ought to make sure the players do not get stale. But they seldom do. Instead they approve of the typical American training system, you know the recipe: plenty of hard physieal work, concentrate-upon-the-game sorl of thing, a method that may be well adapted to football but is not suited to a sport of a vastly different nature. The preparation of the American Davis Cup teams in Paris has always seemed to me singularly devoid of intelligence.

Continued on page 58

Continued from page 49

There is far too much directing, and there are far too many officials in lawn tennis everywhere. In this connection an amusing incident happened during the Challenge Round in Paris last summer. The previous year there had been a plague of resquilleurs: gate crashers is the word, I suppose. There were the cousins of Borotra, the uncles of Cochet, the lad with the dozen boxes of new balls he had to deposit with the umpire, and which when so deposited turned out to be empty. Many and subtle were the tricks used to get past the guardians at the gate. So the order went forth to watch zealously for the French prototype of One-Eyed Connolly, and admit no one without a ticket. Just before the VinesBorotra match, an impressive individual, hatless, coatless, arrived at the main entrance and shook the guard by the arm.

"Attention! Watch every ticket. Scrutinize every pasteboard. Be merciless. Allow no one in without their ticket. And in case of trouble, remember, call me." Then, squaring his shoulders, he walked rapidly past into the stadium. As the gatekeeper said afterwards: "Monsieur, there were so many officials, I did not know. ... I thought one more or less . . ."

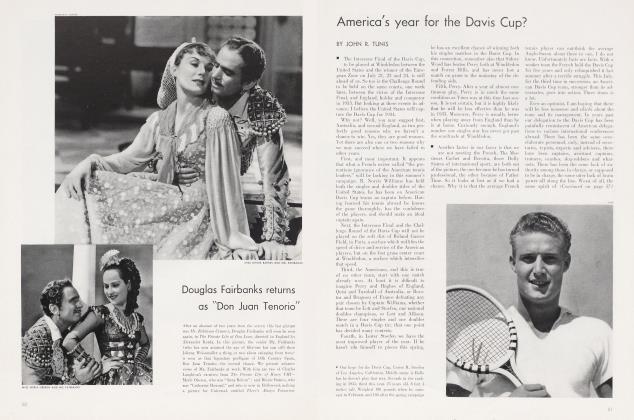

Is an older, non-playing captain necessary or useful to a Davis Cup team? I am not so sure. It is noticeable that while the French have a non-playing captain, it is the men on the field who decide the most important questions of strategy. Suppose Mr. Knox, the president of the United States Lawn Tennis Association, said to Wilmer Allison:

"Here, Wilmer, take your gang over there and bring home that Davis Cup. You'll have a manager to attend to all details, hut on the court you're captain. What you say, goes."

Suppose he did! And suppose Allison was made captain. Maybe it wouldn't work out. We might lose. But just where have we got in the past five years with older and more experienced gentlemen showing the boys how it should be done? I mentioned, as one factor in our failures abroad, the disposition of our team in the Challenge Round. Second guessing is not difficult; but if Hunter had been used instead of Lott in 1929, if Allison had replaced Wood against England in 1931, if Lott had teamed with Van Ryn, and Allison been given a rest on the second day in 1932, the Davis Cup would now be ours. It has yet to be proved to my satisfaction that in these as in other matters the elder men are more capable than their juniors.

This said, these facts noted, haven't we really lost because we couldn't win? Isn't it true that the French galleries are really badly behaved? Aren't their linesmen simply awful? Didn't someone change the texture of the court at the last minute on the final afternoon of 1932? Weren't we, in short, more or less done out of the Davis Cup? To all these questions except the third, the answer is no. It is true that on that fatal Sunday the court was so soaked that a cessation of hostilities was in the mind of the American captain. Whether purposely done or not, this drenching of the court reacted chiefly upon Borotra, a Frenchman. He suffered most of all.

Sporting chauvinism is a curious thing. Last September Henri Cochet returned to Paris after the American championships declaring that the decisions were heartbreaking. If you were at Forest Hills last fall you know this to he absurd. There were some bad decisions in Paris during the Challenge Round in 1932. There always are. But only one was really vital, the service ball of Borotra's which was called good at match point, a decision considered incorrect by many Frenchmen. Yet the finest comment on this incident was made by the person most concerned: Wilmer Allison. Discussing it in the quiet calm of the lounge of the Olympic several days later, he said, thinking of those three match points Borotra had saved before that contested decision: "Well, I had my chance and couldn't take it."

But that French crowd? Aren't they a pretty bad lot? No better, as a rule, and no worse than an American gallery. For at Roland Garros Field fully half the stadium is filled with foreigners. The most prejudiced, chauvinistic, unsportsmanlike crowd I have ever seen in considerable experience 3vas not in Europe but in the City of Brotherly Love when Cochet was playing Johnston in the Challenge Round of 1927 at Germantown. In my opinion, French galleries compare favorably with those in this country. Nowhere did Bill Tilden ever get such a reception as from the ranks of Tuscany in those cheap standing places at Roland Garros.

Naturally, it is more difficult to play abroad than at home. We must be prepared to have the breaks go against us. We must accept both a court and hall unsuited to American speed of drive and service. But inefficient leadership is a handicap we need not support. Our team should come to the Challenge Round fit and keen, not jaded and overtrained.

Vines is a great player. But events of the winter proved he is not invincible, even if he is the best singles star of the world today. Allison is hardly likely to be better than in 1932. With Van Ryn, his team has lost in homogeneity. Cochet on the other hand will almost certainly he in better form than in 1932. For this reason the battle, if we get to the Challenge Round, which is by no means assured, will he desperately close. Physical and mental fitness in all probability can turn the scales between two evenly balanced teams.

I started to write on the reasons why we lost the Davis Cup. You may retort that we haven't lost it yet. True. But although we shall receive a handicap of fifteen years per man this summer, neither have we won it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now