Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

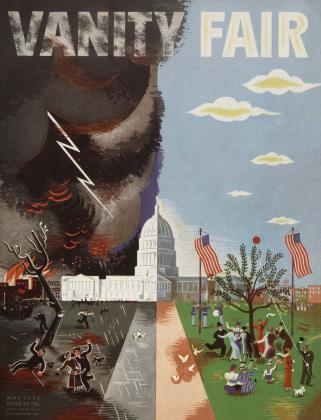

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFrom right to left through Redeemer-land

WILLIAM HARLAN HALE

A look into our parliament of planners, from the mild proposers of reform to the thunderous voices of revolt

ALL GOOD THINGS ARE THREE.—Clinical observers have recognized three stages in the disease of the national patient. The first period of the depression lasted from the October, 1929, market crash to the temporary rise of business early in 1930; the second lasted through the long unbroken decline of 1930 to haul up in the sudden upswing of the Hoover moratorium in June, 1931; the third lasted through the international money crises, the riots and hunger marches, and culminated in the fold-up of the American banking system, at the absolute zero of the economic chart. And these three periods have found their voice in three periods of progressive social and economic thinking.

The leading doctors and redeemers have ranged from moderate to revolutionary in their diagnoses and in the cures they propose; so that, as we scan the photographs on these two pages from left to right, the leaders range from Right to Left. The President of the General Electric Company is at one extreme of the line-up; the head of the Communist Party of America is at the other.

In the first period we heard the excuse, "insufficient consumption"; the idea was to make light of the crash, wish stocks hack up to the balmy levels, and to hold that our "rugged individualism" would he adequate to meet all problems. As nothing could stop us from sliding into our second stage, the patient had to call in specialists, and we grew nervous. Our economic free-for-all was badly hogged; hut at the same time the longdespised Russian system was making a success of its Five-Year Plan. We suddenly felt the crying need for regulation of production and restoration of buying power. In a burst of mental revolution we hit on the idea of Planning. But we planned on paper; soon the country wearied of the sport. The third disease period brought defeatism and hysteria with it. Squatter camps, nomad youths, barter groups, signified a return to primitive life; college men, without hope of jobs, rushed into the strengthening Communist ranks; "rugged individuals" sent out their S.O.S., and the Republicans were forced to dabble with Socialism. Economists and planners were scattered in confusion. March 4th the curtain was rung down, with a crash.

MEN ON THE LIBERAL BENCH.—Today, in the period of mental suspension following the end of an old order and the rounding-out of Mr. Roosevelt's highly-powered New Deal program, there have survived a small hut emphatic group of men who are leading the various planning and left-wing movements. Their work seems to have made a lasting impression on the American mind.

Gerard Swope (the first in our group of pictures) is one of those liberal industrialists who think also of the welfare of their employees and of the wider responsibilities of business life. His work at the head of the General Electric led him to his famed Industrial Plan for the entire country, which proposes a union of government and industry—the very opposite of the old doctrine of "keeping government out of business." It looks to the formation of national cartels or associations within the various trades and industries, which would work to limit competition, control production, protect investors, and give the workingman extensive insurance benefits. The whole structure would he controlled directly by the government, acting through the Federal Trade Commission or some newlycreated bureau. In other words, the idea is: extend to the nation at large the efficiency of technique which we now find only in single industries.

Walter Lippmann (our No. 2) is a liberal of similar degree. Although a general thinker rather than an exact planner, he has. through his daily editorials, built up what approaches a full philosophy of government. Emphatic on the reform of banking and legislative processes, he is making himself now felt primarily as an advocate of an American dictatorship, of a high degree of centralized authority. This rather gets him away from liberalism, but Mr. Lippmann's mental agility is great.

Charles A. Beard, historian, comes out of the progressive movement of the elder Roosevelt period; he is now a planner par excellence. Like Swope, he insists on cooperative action; but he looks forward to great "syndicates" to carry out large-scale farming, marketing, and exporting—all to the end of eliminating middle-men and the speculator's game. These syndicates are servants of a National Economic Council and a Planning Board whose purpose is to survey our productive needs, coordinate our national work, and insure a higher standard of living for everyone. Just how these gigantic ventures are to be ushered into existence, Dr. Beard does not reveal.

ENVOYS TO A NEW SOCIETY.—With Oswald Garrison Villard (No. 4), publisher of The Nation, we move leftward to the Socialist benches. The man is so identified with his magazine and the figures of his group that his own personal doctrines are hard to identify. But beside being a passionate free-trader, internationalist, and opponent of the suppressions that American liberty has given us, he follows the Socialist "Tax the Rich ' policy, and is a leading inflationist. His magazine calls for a general 50% devaluation of the world's currencies as one solution to the crisis.

Stuart Chase and George Soule, authors of distinguished books which lay out the blueprints of a planned society, are both leaders of the non-political school sometimes named "parlor-pink." Both call for a radical redistribution of income, for a dependable and widely diffused purchasing power as the basis for a new prosperity. With the hope of ending turbulent competition, unemployment, and "business cycles," they propose National Boards of experts who are to plan all major production. There must be rigid control of capital investment, and effective curb on profit-taking. The consumer must be protected (note Mr. Chase's work in founding Consumers' Research I ; the working class must be given a New Deal that is more than a half-way measure. Scholars and authors rather than propagandists, both Chase and Soule avoid any radical party activities, and shy from the idea of actual revolution.

THUNDER ON THE LEFT—With Howard Scott (No. 7), technocratic wizard of world fame in December and oblivion in January, we mount to the radical benches of our planning parliament. Believing that the basis of physical wealth is energy, Mr. Scott holds that the only men fit to rule us are the handlers of energy—engineers. Last winter he showered upon America barrages of statistics to prove that our uncontrolled production must lead to more and more unemployment, and that our investment must lead to a greater and greater accumulation of debt, with collapse inevitable. In his more imaginative moments he proposed a national currency based on energy-units rather than gold-units; he guaranteed, under his system, a $20,000 a year income for one and all, plus unlimited leisure. Unfortunately many of his figures were found to be badly off, and his terms bungled. The editorial writers, aching to get rid of a complex of ideas that was too much for them, wiped the floor with Mr. Scott. The movement died like Tom Thumb golf and Humanism, and the jig-saw puzzle came in. But Mr. Scott is only one of a chain of critics that began with the great Thorstein Veblen; and his ideas are here to stay.

Less known in this country than his other planning colleagues, Major C. H. Douglas (No. 8) nevertheless represents an important body of radical thought. A British engineer, inventor, and director of the Royal Aircraft Works during the war, he has aroused the Empire as well as many Americans by his "Social Credit" plan. He protests against the old business man's doctrine of "Produce more and consume less"; what he looks for is an increase in consumption, unaccompanied by the usual increase in prices. A vastly heightened national buying power is needed. Major Douglas solves the problem by a universal money grant (which is more like Scott's guaranteed income than like President Hoover's painful "dole"). Where does this money come from? Well, it is all rather complicated. Major Douglas argues that our accumulated past achievements together with our immense potential power of producing goods have built up a giant reserve of national wealth, which can be converted into "real credit". Given a new society in which the banker and broker have been eliminated, each citizen could thus obtain, beside his earned income, a share of the "National Dividend." Despite the great complexities of his theory, Major Douglas has an army of followers: he counts 100.000 disciples in Australia (where some of his ideas are in practice), IM. P.'s of Social Credit persuasion in Canada, and a growing audience in Ireland.

With William Z. Foster, our final figure, we reach the Extreme Left—the "Mountain" of this reforming tribunal. Mr. Foster is a planner only insofar as he is head of the Communist Party of America. There are four Communist Parties on our democratic shores, but the other three are factions that have broken away, through arguments over theory, from the mother group. Moscow recognizes only Mr. Foster and his vanguard. This small group looks down upon the great number of intellectuals who have swarmed over to Communism and have practically monopolized its publicity. It tries to avoid the company of most of the young poets and ci-devant aesthetes who are now writing "proletarian" novels and criticism. But despite this dislike of intellectualism, the party itself has gone intellectual in that it is always throwing members out over minor disputes in doctrine, and branding them as "traitors" and "counter-revolutionaries". The party is more intent on purging its membership and avoiding compromises than it is on achieving any notable gains in voting influence. In the last election, at a time when 12,000.000 unemployed walked the streets, it polled a scant 100.000 votes—thus revealing that it had made no impact upon the American mass mind. Despite the leadership of Mr. Foster, who is an old labor union man of known ability, the party remains a focus for nonlaboring people: notably writers and the Platos of Union Square.

THE TECHNIQUE OF FAILURE.—What has been achieved? No Plan is in effect; no State Socialism has arrived among us; no "National Dividend" is about to be sent to our homes, on checks signed by the Treasurer of the United States. The brainy gentlemen have talked and gotten no results. What is the trouble?

The trouble is that none of these planners know or care anything about politics. 1 hey are so intent on working out utopias that they do not stop to show us a way to effect one single improvement. They are unable to form a Third Party movement, because some vote the Democratic ticket, some the Socialist ticket, some the Communist, and some are altogether at sea. Only the frankly revolutionary leaders have what is called "political leverage"; but their stress on a class war has found singularly little meaning for this country. The rest—the Beards and Villards and Chases—seem doomed to remain intelligent "progressives", eminently readable, but without concrete effect. They are the doctors of our nation, to be called in when the organism goes wrong; but they do not seem to be the builders of the nation.

IN THE BEGINNING WAS THE WORD.—But now you come on an old problem of history. Which comes first in the annals of man: the deed or the idea? Was a Renaissance possible without the long period of critical preparation by poets and thinkers and artists? Was a French Revolution possible without a century of Voltaires and Diderots who cleared the air? Didn't the new religion of Equality do more to start our own Revolution than the Stamp Tax, and didn't old Professor Marx, thinking thoughts in obscure German libraries, do more to launch Communism than the Czar's fusiliers?

Even if the progressives and planners of our present years have not whipped up a tide of popular fervor, are they doomed to failure? Their body of thought, and their ideal of community and cooperation, have seeped deeper into the mind of the nation than we may imagine. As the Hoovers and Mellons and Owen Youngs have undergone their sad deflation in the eyes of our people, a new ideal has come among us. A period of mental preparation has begun.

And, like all democracies, we move forward hesitantly, by compromise. What then is President Roosevelt's New Deal but a very modified approach to the New Deal of the radicals? His ideas of national banking control, public enterprise, and federal support of the people's buying power,—who prepared America for these, if not the planners and professors, in their ineffectiveness?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now