Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Cardiff giant

EDMUND PEARSON

One day in October, 1869. five men were digging on u farm, in the village of Cardiff, south of Syracuse. N. Y. The owner of the farm was an inoffensive man of thirty-five, called "Stubb" Newell. He had engaged the other four to help dig a well, although be had a well, and the spot chosen for the new one was not promising. At the depth of five feet, one of the shovels struck something hard, which proved to be a gigantic stone foot. The digger shouted: "Jerusalem! it's a big Injun!" They all set to work, and in an hour bad uncovered the stone figure of a naked man, ten feet tall.

In a few hours, thousands of neighbours bad come to see the prodigy. Within a day or two. Newell, who went about things with silent efficiency, put a tent over the pit, and was admitting sight-seers at half a dollar each. Tile proceeds were about $100 an hour; the Newells felt they had a gold mine. When a lady, who had driven out from Syracuse to see the marvel, applied to Mrs. Newell to cook her a dinner, at a juice, that newly-rich matron said that she didn't "do such things now."

In three or four days the metropolitan newspapers were printing columns about "The Petrified Man and "The Onondaga Giant." naming him for the county in which he had been exhumed. The title under which he finally got into the encyclopedias was "The Cardiff Giant." A great controversy broke out as to whether he was a petrified Indian chief, of unusually noble proportions; or a pre-historic statue of mystic significance. Stubb Newell offered no opinion, but continued to stand and take in half-dollars—two hundred of them every sixty minutes.

Awful solemnity surrounded the Giant. His appearance was portentous; some of the clergy hastened to endorse him as of sacred importance, confirming something or other in Holy Writ; while the profane multitude looked upon him with extreme reverence, since he bad such tremendous commercial value. Inside a week, Newell had refused an offer of 810.000; and sold a three-quarters interest for $37,500. He kept a one-fourth interest. One of the syndicate of five which bought a controlling interest was David H. Hannum, a horse-trader and hanker, who once seemed to have been immortalized in American fiction as the original of David Harum.

Pictures of the Giant are unsatisfactory, and usually incorrect. Of all those who saw him, while he rested in his early bed, the most intelligent observer was President White of Cornell. His carriage joined the procession which blocked the country roads in every direction, all going to the farm. The scene, in the subdued light of the tent, he says, was uncanny. The visitors took an almost religious attitude; people hardly dared speak above a whisper. The gigantic naked figure was apparently made of gray limestone, though its colour suggested long burial. It lay on its back, its legs drawn u as in agony. There were minute punctures on the surface of the body, like pores of the skin; while on the back were grooves such as might he made by streams of water. It had no great artistic merit, and could not have been carved by a sculptor of genius, yet it vaguely recalled certain noted statues, as, for instance, Michel angelo's Night and Morning.

There were some oddities about the Giant. He could not he a statue or an idol, men said, because of his recumbent position, like someone who had "lain down and died". Pounding on him. some experimenters thought he sounded hollow. And there were the pores in his "skin".

But he could not be a man, because lie was devoid of any traces of hair. One old farmer said that unless they showed him some of the coffin, lie would refuse to accept the Giant as a "putrified man".

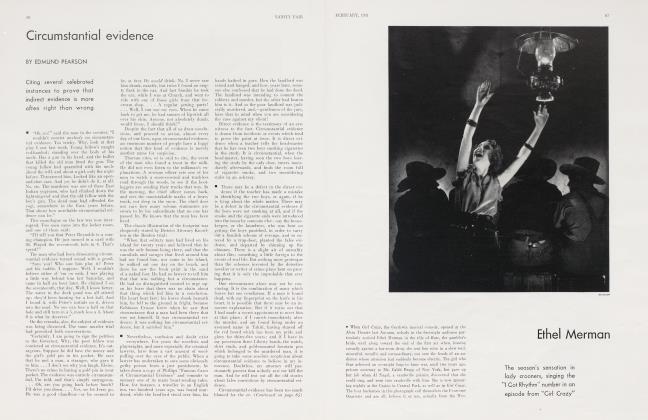

Mark Twain, at a later date, wrote a tale about him; it is called A Ghost Story, and relates an encounter with the Giant's spectre. The picture with it seems to reproduce the bland, rather sleepy expression of the enormous features. If lie was a prehistoric statue, the ancient sculptor had foreseen, with remarkable clairvoyance, the qualms of the I860 s as to the nude in art, since the Giant had adopted the modest gesture of the Medici Venus.

Soon lie started on his travels. He weighed about 3000 pounds and was rather brittle, hut a showman was engaged as manager, and the Giant was put on exhibition in Syracuse, and hooked for Albany, New York. New Haven and Boston. Great grief how the money rolled in! An offer of $15,000 for a one-eighth interest was refused and the investment was said to he paying the equivalent of 7% on $3.000.000. They had to run special trains into Syracuse. Barnum tried to buy the Giant for his New York museum, and failing to do so, made an imitation giant, which did fairly well, to the great rage of the promoters of the original.

Geologists and other learned men arrived early at the Giant's bedside. A local scientist, one Dr. Boynton, was much impressed; his was the first offer, of $10,000. Dr. Hall, the State Geologist, thought that the evidence of long burial was clear; and in a cautious statement declared that the figure deserved "the attention of archaeologists."

According to one theory, the Giant was "the work of early Jesuit fathers"—upon whose hands, apparently, time had hung heavy. Another story had it that he was a statue of St. Paul, by a mad Canadian artist, named Jules Geraud, who had died of sorrow and neglect. The Giant, asserted the New York Herald, within a fortnight of his discovery, was "a stupendous hoax." The Herald, in the same issue, printed the story of the Canadian sculptor. According to others, the Giant was the petrified body of a gigantic Indian prophet. Anybody who sneered about him was rather unpopular in Syracuse, the local boosters naturally regarded doubt as high treason. Certain devout folk regarded him with tenderness, and rebuked all scoffers. Some of them discovered great artistic beauty in the figure. Clergymen impressively quoted Genesis, 6:4, "There were giants in the earth in those days". They seemed to think that this was a knockout blow for sceptics like Bob Ingersoll. Poems were addressed to the image:

"Speak out, O Giant! stiff, and stark, and grim."

Professor 0. C. Marsh of Yale bluntly said that the Giant was of modern origin and an obvious humbug. He pointed out that the substance of the statue was gypsum, which would have dissolved in the wet earth in which it was found, had it long been there. He discovered recent marks of tools upon the surface. Men of a neighbouring village began to remember the mysterious nocturnal visit of a party of men to a wayside tavern, a year earlier. They were conveying an enormous box. said to contain "agricultural machinery", and drawn by a four-horse team. The man in charge was an "infidel", who loved to wrangle about religion, and attack the orthodox beliefs of loafers in bar-rooms. He was soon recognized as a frequent visitor to the farm; and. in fact, proved to he Stubb's brother-in-law. His name was George Hull, a tobacconist. That he came, not from Syracuse, but from Binghamton, is a solace to the Syracusans, even today.

Continued on page 102

Continued from page 64

When it was found that Newell had been sending large stacks of money to Hull, and when distant people in Iowa and Chicago began to remember past events, interest in the Giant was renewed, and gate-money continued to pour in. Mr. Hull did not keep up the deception for long. He had achieved one of his objects, in collecting $60,000 as his share—although he soon lost it in business. He now wished to enjoy another fruit of his enterprise. He nursed a curious desire to revenge himself upon an insignificant Methodist preacher, the Rev. Mr. Turk of Iowa.

With this gentleman, three years earlier, he had engaged in one of his arguments on theology. Mr. Turk was a revivalist, and by virtue of superior wind and louder shouting, had quite discomfited the tobacco dealer. The whole case, for or against Divine Revelation, seemed in the dialectics of these worthies, to hinge upon that text in Genesis, about giants. So Mr. Hull, who combined in his character the elaborate practical joker with the village atheist, had devoted two or three years to this curious riposte.

With incredible labour, and at an expense which included the purchase of an acre of quarry land in Iowa, the great slab, weighing three and a half tons, was hewn from a gypsum-bed near Fort Dodge. It was carried over forty miles of bad road to a railway station, and thence by train to Chicago. Here, in a barn, the "divine artists", a German named Salle and an American named Markham, evolved the Giant. The slab had been shortened, hence the sculptors had to draw up the legs, and give the figure its strange and distorted appearance. They worked long and carefully to make it look antique and worn by water; washed it with various chemicals; and pecked at the entire carcass with leaden hammers faced with needles, so as to produce the "pores".

Mr. Hull had intended to bury the Giant in Salisbury, Connecticut, but fortunately abandoned this plan in favor of his brother-in-law's farm. The name Cardiff, attached to the statue, was always of great value, for its archaic sound, and general flavor of giants.

Hull's confession did not entirely kill the image as an investment, nor by any means confound some of those who liked to believe in its semi-sacred character.

The Petrified Man business was carried on for twenty years. Hull dug up another in Colorado; a man named Ruddock found a small, mean giant in Michigan; and in 1889 the game had reached Australia.

As for the original colossus of Cardiff, his fate was that of many a veteran trouper. If we may believe a stray newspaper clipping, the Giant was attached for debt, and lay for many years, cold and lonesome, in a freight house in Cheyenne. An unknown writer for the Chicago TimesHerald often saw him in his solitary shame. At last he went on the road again. A railway station in Missouri burned down; the poor old Giant was staying there at the time, and when the firemen looked in, he was a complete casualty.

Postscript—This sad ending of the story of the Cardiff Giant is the one which I, an uncompromising realist, naturally prefer. Later information denies his fiery fate, and takes him back to his home at Fort Dodge, near the old gypsum-bed. There he was last seen, slumbering at ease in a public park. This happy ending will be preferred by the producers of moving pictures. Disputes are sure to arise about him, since there were said to be no less than four replicas of the Cardiff figure.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now