Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMy severe attack of whimsy

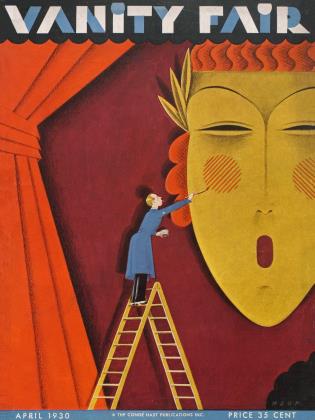

ROGER DU BÉARN

Wherein it is shown that too much fancy, like a little wisdom, is a dangerous thing

■ "Crumbs," said I, "toast-crumbs, cannot

be swept out of a bed. You must burn the bed."

"Ah?" said she.

"Yes," said I.

"Oh!" said she.

...and so on, for at least thirteen paragraphs, equally long, which constitute Chapter I. It must be laid (and laid on thick) in Sussex or Surrey or Surrogate (the famous court of fashion). It is there, in fact, and I am a languid blond youth who drawls pleasantly in faultless flannels. These must be worn carelessly, so carelessly that one is in perpetual danger of arrest for indecent exposure, and the audience in perpetual hopes of the same eventuality. The chief reason I am not taken in by the constable, however, is that I never leave Shoddymanse Old Park, or whatever the delicious rambling Tudor countryhouse is called.

The girl is named Edith and must be a tall blonde, unless she happens to be a small brunette. A large brunette, or for that matter, a small blonde, can never be whimsical. We two young people, naturally, are in love, but carelessly, whimsically, like our clothes. That is to say, we never get beyond holding hands and chaffing. We chaff each other blue in the face and pink in the gills, trying to do it and look indifferent at the same time. It is not so easy as it looks. For one thing, we are on the rack thinking up ungrammatical replies to each other's unfinished sentences. For another, we must suspend our audience for the length of a "thin volume" that "never fails to be charming, whimsical, and $1.50 net."

■ So we go on something like this. (We are

now in the midst of Chapter Fourteen, but the order of chapters is as arbitrary as that of the sentences.)

"Oh, as for that," says Edith.

"Yes?"

"Why, ever since . . . I've felt . . ." She pushes the invisible world over the side of the small punt. (You see, we are on the Brwhshll, that charming, whimsical little stream which crosses Shoddymanse Old Park along an avenue of willows.) I continue digging the river-bed with a long pole, then,

"Felt . . . semi-detached?" I venture, not knowing in the least how she feels.

"Hmmm. . . . That's it," she replies, looking up into my face, perhaps to get a hint of what we are talking about.

"If one only knew . . (This is safe ground.)

"The cause?"

"The reason!"

"Perhaps I can . . ."

"You might . . ." (She looks coy—or is it my move?) "but you won't . .

"May I ask?"

"Why? Naturally . . . why, er—because

now really you're a great deal too whims—"

Her narrow escape from an intelligible reply rocks the boat perilously. "I may be two whims, or even three," I reply a little lamely, "but I hate a ducking . . . flannels shrink so . . ." And I bring the punt under a willow, while you go on to Chapter Seven.

After two or three thin-volumes at one-fifty net, you, Dear Reader, are no longer confused. You expect certain things, and get them, or know the reason why. You get innumerable picnic-parties and boating-parties, and garden-parties, and house-parties, and hunting-parties, and barn-parties, and cricketparties, and masquerade-parties. It makes little difference what the setting, you get your legal dosage of whims.

The course of true whimsy does not always run smooth.

■ The suspense in our affections is as .trying to us as it may be titillating to you. It is true we are helped out by Edith's father, an old fool who happens to be the Prime Minister, but even so, there is a limit to human stupidity. I cannot conscientiously say Edith's father is the limit.

At any rate, he is good enough to refuse his consent to our marriage, which ought to last about ten chapters—the refusal, I mean. To clinch it, in the middle of Chapter Fifty-Two, Edith, pointing in my general direction, says:

"Papa, please buy the brute for me."

"He ... he doesn't growl properly," answers the old gentleman. Whereupon I proceed to crawl on all fours and vindicate myself.

"I didn't mean quite that," says the Prime Minister. "You growl very nicely, Roger, very nicely indeed. The truth is, when I spoke in the House last week about reducing the Navy's gross tonnage, a member of the Opposition buttonholed me, "Speaking of gross tonnage," he said, "I should like to marry your daughter."

"Well?" asks Edith breathlessly.

"Well, I didn't quite see what he was driving at just then, and I'm afraid I pledged the Government would take all measures necessary to insure the execution of his statesmanlike suggestion."

"That was rather stupid," I break in, with immense relief, and to put the old man at his ease.

"Ah, but the worst of it is, Roger, I don't half remember the fellow's name!"

The Member of the Opposition is a wellkept, beef-red fellow of fifty who, we have decided, at any moment, will come to claim his promised bride. The affair, in its innocent whimsical way, assumes imperial proportions. If the poor girl refuses him, the Government will be ousted, papa will be one of the unemployed, and I shall have to advertise for another heiress. . . . Whimsy, as Edith once beautifully said, is but the film of romance over the badly-brushed teeth of tragedy.

And yet, there is worse. That is when Edith and I quarrel. We occasionally play cricket, just the two of us, as you know, having borrowed a wicket from the railway-station and a bowler from the footman; or we disconnectedly discourse with the gardener about his golden laudanum in bloom; then it is that we disagree. Edith does something that isn't cricket, and I pick a flower when she insists that they -ought to be pulled. We are too lazy to be anything but good-natured, and we try to make-up, but since we can't kiss, our efforts end in failure.

"Perhaps you'll find me less nerve-wracking, now," she begins, none too hopefully.

"I trust so. But I'm not making any promises: my nerves are so independent."

"Well, it's nice of you to admit it. It takes all the ugliness out of their behavior."

"I'm really sorry. I know I sound formal, but I am,—I mean, formal—no! Sorry,—I meant sorry, not formal. Anyway, it isn't nerves."

"No?"

"No. It's just that—oh! you had better go into the house quickly, or I shall say something I mean and insult you, all in one breath."

"I won't mind, so long as you don't ask me why."

"Oh, but I will. Because you'll look puzzled, and I shall say, 'Why?' and you'll say, 'Why, what?' and I shall reply, 'Never mind' or 'Dammitall!', perhaps both."

"That would be lovely."

■ "Yes, with the family trooping out to look for the corpse."

"What corpse?"

"There you go! Your corpse. Can't you think that far ahead? It's only going to be a few minutes . . ."

"If you don't mind, Roger, I'll go in and call for the police."

"Not now, they're probably busy."

"This is important, though."

"I attach not the slightest significance to the incident, and you may quote me as saying so."

"Rather difficult, when I'm a corpse."

"Anything is possible, and with you, I should say, likely."

"Are you trying to quarrel, Roger?"

"It's hard enough without your assistance. Why do you think it?"

Continued on page 90

(Continued from page 59)

"Why do you pick on a friend?" (She calls it freend, after A. A. Milne.)

"Do be reasonable. I can't quarrel with a stranger, can I?"

"Why not?"

"I wouldn't know enough about him to make him angry."

"About whom?"

"The mysterious stranger, of course!"

"Who is he?"

"How should I know, if he's a stranger! . .

It is obvious that, without disparaging each other's company, Edith and I are in a vicious circle. The only thing that will preserve a semblance of whimsical amity until the happy confusion at the end, is to keep away from each other. Reconciliation must ensue from the intercession of the Member of the Opposition, whose secretary reminds him that he already has a wife in the colonies, and therefore, had better not repeat a costly mistake. That is the way Edith and I might be enabled to resume our chaffing.

There is luckily one other alternative to our complete estrangement. That alternative is to invoke the butler.

Edith interviews him in his pantry, the only place where he is allowed to talk like Sir James Barrie, that is to say, a good deal of Sentimental Tommy-rot. Then I wander in casually and he lectures me like Bernard Shaw on the necessity of knowing the Workmen's Compensation Act before getting married. He does more: he reads it to me. Finally, I awake out of a deep sleep.... It seems I have been ill.

Sympathy, grogs, good humor, pillows, and opinions regarding where I had caught my bad cold had enveloped me for a week. About Sunday just as I was getting more audible and could sit up to gorge on untoward delicacies and abuse everybody, I received a book. It was called, I believe, "As We Were Saying", or perhaps "When You So Rudely Interrupted Me", I can't remember which, because you see, it was one of those charming, pointless, hazy pieces that remain so charming, pointless, and . . . hazy.

I made the mistake, however, of asking for more, and my dear Edith with touching but misplaced devotion procured them for me. With my money she swelled the already bloated fortunes of A. A. Milne, Christopher Morley, Max Beerbohm, J. M. Barrie, A. P. Herbert, and a host of others, equally familiar, not only with Wonderland, but, with "Alice in Wonderland" also.

I fed, I battened on these, even though most of them I had read before. I swallowed indiscriminately both Twaddle-Dum and Twaddle-Dee. I began to lose the power of speaking in full sentences. I developed a passion for monosyllables. My Oh's and Ah's became charged with whimsicality, if not with meaning. Indeed, I am not cured of my attack of whimsy even now. I am still abed. "Roger," says Edith, "don't you want to get up while I shake the crumbs out of the bed?"

"Crumbs," I reply, "bed-crumbs, cannot be shaken out of a bed. You must burn the bed."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now