Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowfatal ladies

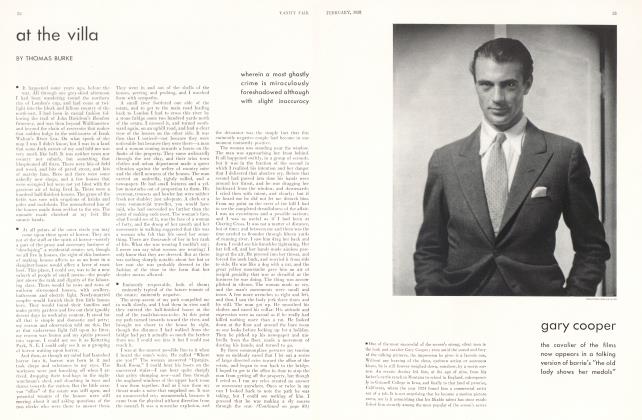

ALDOUS HUXLEY

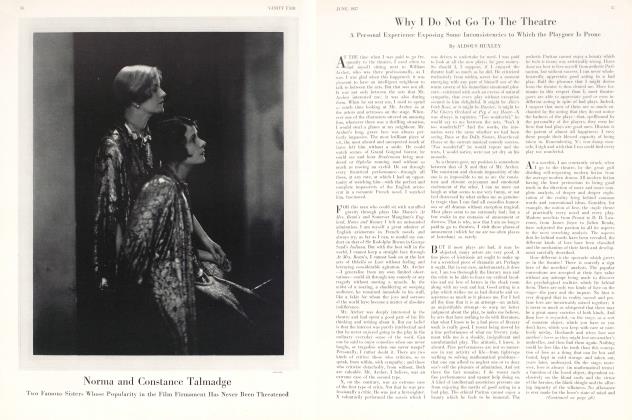

intoning a peculiarly 1930 jeremiad against several varieties of vampire-modern style

Fiction is full of vampires. They flit balefully through the pages of countless novels and their thirsty mouths smile, in gigantic close-ups, from the screens of a million picture palaces. They suck the blood of the aged rich, they lead even the pure-hearted young hero astray, they inflict untold suffering on the blue-eyed heroine, on Mother, on silver-haired Granny. In a word, they are thoroughly Bad Women and the creators of fiction lose no opportunity of making their badness manifest.

In their moral fervour, however, the creators of fiction generally sacrifice artistic verisimilitude and truth to life. For they so blacken the characters of their villainesses and vampires that it is impossible to feel anything for these dangerous creatures but an intense repulsion. But it is not, after all, by repelling people that one can become a successful vampire. A vampire must be attractive. Indeed, the vampire may be defined as an excessively attractive woman who uses her attractiveness to achieve her own ends. Attractiveness is the capital with which she sets up her industry, is the engine with which she makes the wheels go round. We find, therefore, in real life, that the great and successful vampires are the most enchanting creatures. The sinister villainesses of the novel and the film seldom go far in their career. They may catch a few boys, a few perverse or imbecile seniors; but they seldom rise to that exalted sphere where the great historic vampires have their home. Look at a portrait, for example, of Lola Montez. The face is the sweetest, the most enchantingly ingenuous, the most deliciously high spirited that can be imagined. Ninon de Lenclos was wholly adorable. Nell Gwyn was a pet. Personal experience confirms the verdict of history. Of all the large-scale and successful vampires I have ever known most have been irresistibly charming. The obviously sinister Bad Woman of fiction and the films is a type I have only come across in the ranks of the second-rate vampires. Their sinisterness makes them unsuccessful.

The goal of the vampire—like that of every other human being—is self-assertion; self-assertion either by the direct exercise of power over a lover, or in the enjoyment of pleasure and the indulgence in excitements, or else, indirectly, by the amassing of money and its use or display. Many vampires are not mercenary, either because they have no need of money or because they are not avaricious by nature. These assert themselves (as of course do the mercenary ones also) in the first two ways, by using their charm to make slaves and victims and by compelling their slaves and victims to provide them with an uninterrupted succession of stimulating emotions.

For adventuresses of this kind I have always had, I confess, a certain weakness; and if it were not for the fact that I have a still greater weakness for reading and writing books, for family life in the country and meditations about the cosmos, I might very easily have become one of their victims. For if there are natural vampires, there are also natural vampirees, and to this class a part of my being undoubtedly belongs. I love the good old-fashioned adventuress, not only for her own enchanting self, but also because she is so magnificently in the tradition (the great tradition of Helen and Cleopatra, of Diane de Poitiers and Lady Hamilton), so encrusted with historical associations, so classical. She is like holly and plum pudding, or the Parthenon by moonlight, or Tut-ank-Amen's mummy, or jokes about mothers-in-law—hallowed. In her presence I feel, among other emotions, what Wordsworth describes as "natural piety." She makes me want to lay a wreath on her, as though she were Shakespeare's tomb or the brass plate where Nelson fell.

But there is another cl ass of adventuress, another species of vampire, for whom my feelings are very different. I refer to those abandoned creatures whom I may be permitted to call vampires of the soul, or spiritual adventuresses. These I detest, these I utterly reprobate. They inspire me with a high moral indignation—perhaps, as is usual with high moral indignations, because I am rather afraid of them. With the old-fashioned adventuress one knows exactly where one stands. There she is—out for power, for money, for a good time, for every form of physical and emotional excitement. It is all entirely aboveboard and obvious. But with the spiritual vampire nothing is obvious; on the contrary everything is most horribly turbid and obscure and slimy. For the horror of the spiritual vampire is that she doesn't want money, or the ordinary excitements, or the commonplace good time. She wants Higher Things; she's out to assert herself on the Higher Planes. The old-fashioned adventuress feels happy if she has large pearls and a large automobile. But the spiritual vamp is only satisfied if she can persuade herself that she has a large soul and a large intellect—not to mention high ideals and a wide culture, and deep thoughts.

The appointed victims of the spiritual adventuresses, their ordained and predestined vampirees, are not the rich in cash, but the rich in mind—or at any rate, those who believe or can be persuaded that they are rich in mind. For in order to get their famous Higher Things, in order to assert themselves on the Higher Plane, they must get hold of a Higher Person, or somebody who passes as a Higher Person. So they attach themselves like leaches to the highest specimen they can find. Contact with the Higher Person makes them feel agreeably high themselves. It enhances their sense of importance, it gives significance to their horrid little personalities, it satisfies their parasitic will-to-power, it permits them to assert their leechlike selves.

Continued on page 98

Continued from page 31

In the past these spiritual vampires would have got their fulfilment from organized religion. They could have fastened themselves on the nearest priest and made him the director of their conscience. (How flattering and gratifying to think that one's conscience is so important that it requires directors like a railway company or a department store!) Or alternatively they could have sucked the spiritual blood of some saint or other invisible Higher Person. But now that organized religion has decayed, most spiritual adventuresses are without those professional victims which a far-seeing and all too charitable Church used to provide for them. They have nobody to attaoh themselves to but a few charlatans and swamis and higher-thoughtmongers and psychoanalysts, or artists. The souls of these last, it seems, are particularly juicy. To the spiritual vampire an artist is almost the choicest of delicacies.

The spiritual vampire is a modern type, whose development, as I have already indicated, was made possible only by the decay of organized religion. The feminist movement has also done much to propagate this baleful creature. For feminism has wearyingly insisted on the importance for women of that Higher Plane, on which the spiritual vampires try to assert themselves, and has disparaged the qualities of charm and allurement which have always given and still give to the dear old-fashioned adventuresses their deserved and, by me at least, ungrudged power. A history of the spiritual vampire, if it were ever written, would be, I am sure, a most instructive and illuminating book. I lack the erudition to undertake the task. It is my impression, however, that the new species only assumed its characteristically modern and menacing form during the Romantic Period of the nineteenth century. It is, I believe, among the lesser contemporaries of George Sand (George herself was not a mere vampire, she was a man-eating lioness) that we shall find the fully developed spiritual adventuress of the type we can observe to-day. Nor must we forget that the contemporary vampire of the soul seems to be undergoing, among the youngest generations, a process of change. Among the extremely young there seems to be a diminishing interest in any of the Higher Things that are in the least objective, that exist apart from the individual soul. High ideals, wide culture, deep thoughts are not nearly so popular among young vampires as they were twenty years ago. The youngest vampires are almost exclusively interested in personalities, in the problems of their private psychologies. Their mothers attached themselves to those Higher Persons who stood for Movements, Causes, Ideals. But Movements have ceased to move; it is to the Higher Person who can talk to her about herself that the youngest spiritual vampire turns. Self-assertion is undisguisedly and directly her aim. Which is regrettable. For if there is anybody more boring than a soulless philistine it is a soulful philistine. A soulful philistine is a person without culture, without external interests, who goes in for having a soul. But if you go in for having nothing but a soul, you run the risk of going mad—mad with self-consciousness and vanity and bewilderment, the hopeless bewilderment that comes to everyone who is utterly without culture and to whom every fact and experience presents itself as isolated and unconnected, a bright point floating about with other points in the midst of unfathomable darkness. I have met—met only to avoid as rapidly and radically as I could—quite a number of these soulful philistines, gone a little queer in the head with poring over the obscurities of their own boring and repulsive personalities; soulful philistines who were also spiritual vampires, hungrily on the lookout for some Higher Person who would talk to them about their souls and so help them to self-assertion. Dreadful creatures, of whom I cannot think without a shudder! Our little vampires of the spirit, our soulful philistines of the youngest and most psychologically minded generations, have still good looks and freshness to palliate their offences. But let them beware before it is too late. The time will come when they will lose those physical excuses for mental perversity, when their bodies will be as unattractive as their minds. And then may heaven help them! For men will not.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now