Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Lady Horse-Thief

The Case of Miss Perkins, Victim of an Ungovernable Attachment to the Equine Species

EDMUND PEARSON

THE strange career of Miss Josephine Amelia Perkins, and her propensity for stealing horses, is explained by an incident of her youth. The only daughter of a gentleman in Devonshire, she was sent, when a young girl, to attend a riding school. Thus, her father was really to blame for all that followed, since Miss Josephine soon excelled every other pupil in the art of horsemanship, and what was of more fatal importance, she acquired what she later called "my present extravagant fondness for those noble animals."

There you have it. She could not help herself. If she so much as looked at a horse, especially a very good horse, she simply had to jump on him and ride away. Sometimes she had to look around for a saddle,—and, of course, for a sidesaddle, since, thank Heaven, she understood propriety. Once, she had to hunt for nearly twentyfour hours, but she found the right saddle, and then came back, by night, and got the horse.

A parallel character in literature is Mr. Toad, in The Wind in the Willows. He had a passion for motor-cars, and when he saw a fine one, standing in an inn-yard, wondered if it started easily. In another moment he was at the wheel, and in another, humming down the highway. But with no notion of stealing a car, mind you.

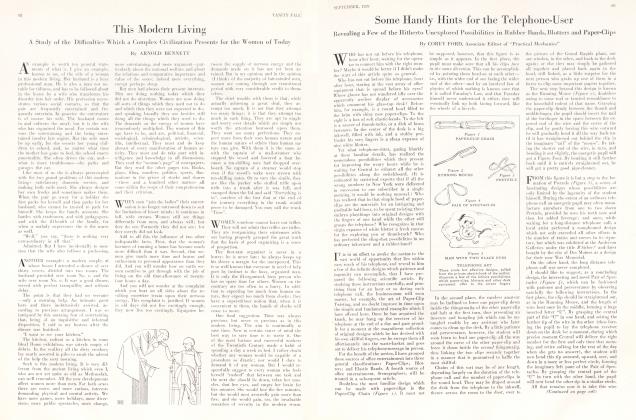

The clumsy criminologists of Miss Perkins' day did not understand that she had what is now known as the Centaur fixation, the equus complex. It makes you steal horses,—but only horses. A cow was perfectly safe with Josephine Perkins. The sheriffs and judges who were forever persecuting her do not seem to have noticed that significant fact. She analyzed her own psychic peculiarities with discernment, when she wrote:

"Ever since I discovered my natural and ungovernable attachment to animals of the horse kind, I never have been without my fears that the attachment would ultimately prove my overthrow."

IT cannot be too emphatically stated that horse-stealing was her only weakness. Aside from a few instances of burglary and sneak-thievery, one or two swindling episodes, and a long campaign of artistic falsehood and imposture (entered into for a very definite object, however) the character of Miss Perkins was, virtually, spotless.

At the age of seventeen, and while living with her father in Devonshire, she had the misfortune to meet a young man "of genteel appearance," who was a purser in the Navy. His courtship was not approved by her father, and an elopement was planned. Josephine was to possess herself of one of her father's fleetest and best horses; ride to Portsmouth; and join her lover on his ship, as it sailed for the North American Station. She was to go aboard "disguised as a male," and as a volunteer seaman.

It involved riding 117 miles in less than twenty-four hours, but to one of the Perkinses of Devonshire there was nothing in the thought to cause an instant's hesitation. She was pursued by her father and uncle, but they rode in vain. She had known which horse to select from her father's stable. At Portsmouth, however, grief awaited: her lover's ship had already sailed. She could not go back, and as resolution was never wanting to her character, she sold the horse, and embarked on another ship for St. John's, intending to proceed to Quebec.

The perils of the deep encompassed her about; the ship was wrecked and had to be abandoned, and at last Miss Perkins found herself in Wilmington, North Carolina. She was nearly destitute, and in great despair for a few days. Then, near the village of Washington, in the same state, she happened upon a fine horse, in a pasture. She marked down his stable, and at night rode him away. She did not know the country, however, and the horse knew it too well; he took her in a circle, and at morning brought her back to Washington, and face to face with the owner. She convinced the magistrate, in this case, that the ride was taken merely "to gratify a whimsical notion"—so her discharge was immediate.

In South Carolina, her luck was hardly better. Here she turned over a stolen horse to a jockey, who sold him for $57, giving her two-thirds of the proceeds. Miss Perkins was nevertheless captured and brought to trial, but enthusiastically acquitted on the grounds of insanity. She resolved to leave the Carolinas, and go to Kentucky, of which she had heard the most favourable accounts.

The state of Kentucky fascinated her. The countryside, the trees, the flowers were all beyond compare. Especially celestial in the sight of the young lady was the Kentuckians' "noble breed of fleet and well-fed horses." So she settled down, and under the name of Sarah Steward, tried to earn a tame and honest livelihood. But the old equus complex was overpowering our young heroine, and in a very short time she found herself in Court, trying to explain how she became possessed of a horse to which another person had a prior claim—and a claim, as Miss Perkins admits, which was good in the eyes of the law.

She was now actually doomed to spend two years in the prison of Madison County. From this dungeon, in May 1839, she addressed the world, in a manifesto called The Female Prisoner. In it she gives a brief history of her life (she was only twenty-one), but devotes more pages to the description of her repentance; her overwhelming regrets for her great transgressions; and her firm adherence to many excellent principles of morality.

Among other precepts which she seeks to inculcate are that it is better to be poor than to be dishonest; that children should obey their parents; that poverty is no disgrace; that virtue is preferable to riches; and that, generally speaking, young girls should avoid horse-stealing, and resist every temptation in that direction—even if the object of their desire is a Kentucky thoroughbred.

With this sound advice, Miss Josephine Perkins disappears from the sight of the antiquarian for about three years. Then, in 1842, she comes once more before the public, and, harrow and alas, this time in a pamphlet called A Demon in Female Apparel: Josephine Amelia Perkins, the notorious female horse thief; again in prison—and for life.

NOW, her repentance is sincere. She maintains that the early part of her narrative was correct—although her vicissitudes have led her into a slight mistake of memory, for in reviewing her escapade in England it is now Liverpool, rather than Portsmouth, to which she fled to join the amorous purser. Nor was there much to correct in her story of her adventures up to the moment she entered Madison County jail. After that, as she sadly admits, hers was a tale of deception, a pretense of reform for the purpose of hoaxing the good ladies, and others, who visited her in her cell.

The ladies had been profoundly distressed that one so bowed down with shame at her faults, one so plainly conscious of sin, should be left to languish in a prison with common felons. So they circulated a petition, and soon had the joy of effecting the release of Josephine Amelia. That lassie had been free but a few days, when the old urge came upon her, and soon she was off again, on the broad highway, and on the best horse she could find.

Moreover, she strayed into conduct which was, at best, unladylike. By means of an old great-coat, and a fur cap, she concealed her sex and passed as a man. There is no suggestion that she so far forgot herself as to abandon her flowing skirts. She bilked tavern-keepers out of their just charges; she travelled about with a young planter, and although it does not appear that their relations for one moment over-stepped the limits of a frigid chastity, she incited him to fraud and deception. She roamed about the shores of the Ohio River, committing various illegal deeds, and at last expressed her abandonment by firing a pistol at a representative of the law's majesty, who came to apprehend her.

Continued on page 124

(Continued from page 73)

When she was brought to trial, she was charged with stealing $150.00 in bank notes; "making an unlawful and outrageous attempt with a deadly weapon upon the life of the officer"; and with various other thefts and high-handed felonies.

She had—she says so, herself—a "mere form of trial," and the aid of but "very imperfect" counsel. It makes our cheeks redden with shame to think that a woman could he so treated, for it must be apparent to anyone, with the slightest knowledge of modern criminology, that Josephine Amelia Perkins was no criminal. But she was sent to the Penitentiary, during the term of her natural life, and so far as any documentary evidence has come to my notice, there she stayed.

Thus did an innocent and amiable girl suffer for the grievous mistake, the wanton blunder, of her father in sending her to a riding-school, and implanting in her psyche, at a tender age, an overmastering predilection for horse-theft. Understanding, sympathy, an intelligent recognition of her fixation were all denied her, and the law was permitted to take its usual stupid course.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now