Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAn Enlightening Essay Concerning a Phrase Which Everybody Knows and Nobody Understands

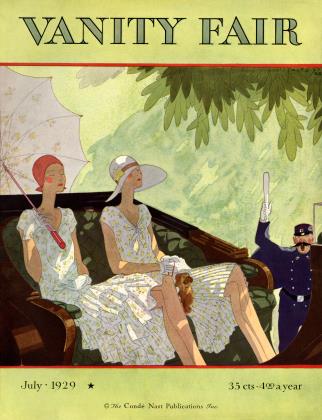

July 1929 D. H. Lawrence View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now