Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBunkers for Use and Beauty

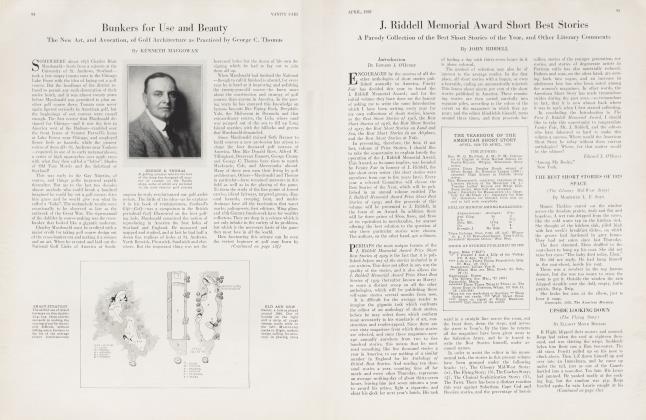

The New Art, and Avocation, of Golf Architecture as Practiced by George C. Thomas

KENNETH MACGOWAN

SOMEWHERE about 1870 Charles Blair Macdonald—fresh from a sojourn at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland— took a few empty tomato cans to the Chicago Lake Front with the idea of laying out a golf course. But the hoodlums of the district refused to permit any such desecration of their native heath, and it was almost twenty years before Macdonald was permitted to plan another golf course there. Tomato cans never again figured seriously in American golf, but the beginnings of our courses were casual enough. The first course that Macdonald designed for Chicago—and it was the first in America west of the Hudson—rambled over the front lawms of Senator Farwell's home at Lake Forest near Chicago, and employed flower beds as hazards, while the pioneer course of them all—St. Andrews near Yonkers —required, in one of its early metamorphoses, a series of high approaches over apple trees with what they then called a "lofter". Shades of Old Tom Morris and the linksland of Scotland!

This was early in the Gay Nineties, of course, and things golfic improved rapidly thereafter. But up to the last two decades almost anybody who could break a hundred imagined he could lay out a golf course. Give him grass and he would give you what he called a "links". The melancholy results were occasionally to be observed as late as the outbreak of the Great War. The sign-manual of the dabbler in course-making was the cross-bunker that looked like a gigantic mole-run.

Charley Macdonald must be credited with a major credit for taking golf course design out of the cross-bunker era and making it a science and an art. When he created and laid out tin' National Golf Links of America at Southampton he truly revolutionized our golf architecture. The birth of the idea—as he explains it in his book of reminiscences, Scotland's Gift—Golf—was a symposium in the British periodical Golf Illustrated on the best golfing hole. Macdonald conceived the notion of reproducing in America the best holes of Scotland and England. He measured and mapped and studied, and at last he had half a dozen fine replicas of holes at St. Andrews, North Berwick, Prestwick, Sandwich and elsewhere. But the important thing was not the borrowed holes but the dozen of his own designing which he had to lay out to join them all up.

When Macdonald had finished the National —though to call it finished is absurd, for every year he is hard at it improving and polishing the twenty-year-old course—he knew more about the construction and strategy of golf courses than anyone in America. In the passing years he has stamped this knowledge on famous lay-outs like Piping Bock, Deepdale, Yale, the Mid-ocean in Bermuda and that extraordinary course, the Lido, where sand was pumped out of the sea to fill up Long Island marshes with the hillocks and greens that Macdonald demanded.

Since Macdonald trained Seth Raynor to build courses a new profession has arisen to shape the four thousand golf courses of America. Men like Donald Ross, Alfred W. Tillinghast, Devereux Emmett, George Crump and George C. Thomas have risen to match Mackenzie, Colt, and Abercromby abroad. Many of these men earn their living by golf architecture. Others—Macdonald and Thomas in particular—have remained amateurs in this field as well as in the playing of the game. To them the study of the fine points of forced carries, island fairways, targeted greens, diagonal hazards, creeping bent, and under-drainage have all the fascination that water marks, palimpsests, first editions, Ming glaze, and i5th Century brush-work have for wealthy collectors. They are deep in a science which is not only infinite in the variety of its problems, but which is the necessary basis of the game they most love in all the world.

How fascinating this science can be even the veriest beginner at golf may learn by reading Robert Hunter's book on golf architecture called The Links. It is written with charm as well as knowledge, and it is easy and ingratiating. Not so easy but far more thorough and more practically useful is the thick volume, Golf Architecture in America, which George C. Thomas has written. Ninety half-tones, four of them in color, and over sixty drawings help to make the text clear and conclusive. No golfer who loves the fine points of the game—whether he can achieve them himself or not—should miss these two hooks, or, for the matter of that, the chapters in Macdonald's which deal with the same topic. They make a day on any golf course so much the richer.

(Continued on page 134)

(Continued from page 94)

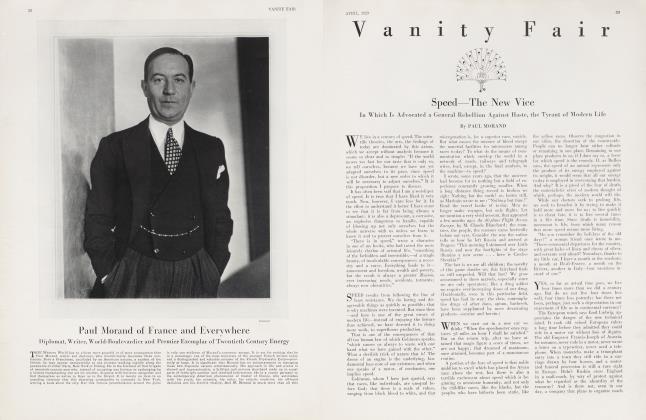

To the average golfer Thomas's book opens amazing vistas, lie stops cursing at the sand trap on the seventh and begins to admire the little roll of ground just short of the green which has been kicking his ball down into this bunker; and next time he plays that hole he takes the trouble to place his approach short of that roll if he can't be sure of getting it over. The golfer stops taking courses for granted and begins to wonder at the ingenuity which has gone into fitting eighteen splendid testing holes into the hundred-odd acres of hill and dale, grass and stubble which nature and the real estate agent rather blindly provided.

Thomas has designed all manner of courses on the Pacific slope—where he now makes his home. They range from the municipal course at Los Angeles to El Caballero, La Cumbre. Ojai, and Bel-Air. He begins his book by picturing the necessary difference between a properly laid out municipal course and the course of an exclusive country club. Difficult traps, short holes, water hazards, deep rough must he avoided on a public course simply because these admirable features will hold up the average player and increase congestion unbearably. From the broad municipal course the complications and refinements of golf architecture mount through the average country club or hotel layout to the ideal championship course like the National or Pine Valley. These complications and refinements make the substance of Thomas's hook.

But first he lays the foundation of nature—the terrain itself. Without proper land the skill of the architect is wasted or only half rewarded. "Nature," says Thomas, "must be big in her mouldings for us to secure the complete exhilaration and joy of golf. The made course cannot compete with the natural one. The truly ideal course must have natural hazards on a large scale for superlative golf. The puny strivings of the architect do not quench our thirst for the ultimate."

And yet how far the architect can improve on nature by the way lie utilizes her! He must be ready to take what she has to give and by the greatest of ingenuity and understanding turn it all to splendid account. One neighbourhood supplies one sort of hazard, another neighbourhood another "Streams and lakes are hazards elsewhere; trees and heavy growth appear in their native districts; rocks cause trouble in other territory; sand dunes are perhaps the ideal hazard, hut all hazards may he used for the same purpose, he they railroad tracks, station masters' house, or "out of hounds."

(Continued on page 136)

(Continued from page 134)

Once past the terrain, you come upon the problem of sizing the best natural spots for tees and greens and then linking these spots together with fairways that provide not only suitable hazards in slopes and rough as well as artificial traps, but also the variety of length and character which must make up a perfect eighteen holes of play. Some holes will seem ready-made. Nature appears to have had them in mind from the beginning. With all the ingenuity of a crossword-puzzler and a mosaic worker the architect must scheme how to link these natural holes together with others that he can create by minor— or major—operations upon Dame Nature herself. Sometimes he must cut off the top of a hill and move the earth down to fill an awkward little marsh. Sometimes he must build an island green to play to from a bluff. Sometimes by diverting a stream he can provide an excellent hazard just short of a drive-and-pitch hole where the original water would have caught the long drive from the tee.

From tee to green the problems are manifold. Tees must be set and fairways laid out with some thought of the prevailing winds and what they mean to the drive. For one hole, three tees providing the same length of carry may be necessary so that the player shall not be compelled to drive into the low' run of a November morning or a June evening. Not only the first tee and the tenth should be near the club house, but the third and the sixteenth also for the convenience of members who may be delayed and wish to pick up their foursomes fifteen or twenty minutes after the start.

Fairways must be considered not merely as so much good turf broken by natural or artificial hazards, but as planes and slopes which will reward the placement of good shots by a longer run, and which will punish weak or reckless efforts by a kick off-line where the next shot will call for a difficult pitch instead of a run-up. In diagram and text Thomas makes much of the multiple or island fairway, a form that we see too seldom in the east. Here the player is given a choice of objectives. He may carry a hundred yards onto a fairway to the right and then use a midiron for a shot just short of some rough over which he must pitch to the green; or if he can carry a hundred and seventy-five yards to another fairway on the right, he will then be able to reach the green with a spoon thanks to an opening between traps.

In construction of traps and greens a hundred considerations come into play. Size depends on length and character of shot. Surrounding objects may help to orient the play. The trap itself may define the green. The sand bunker may protect the green front casual water, or the fairway may have to be moulded to keep drainage out of the trap. And all the while the architect must be thinking both as artist and as scientist. He is creating beauty as well as utility. "The contours of our tees, of our hazards, of our greens, of our rough and of our fairways should, except when otherwise absolutely -necessary, all melt into the land surrounding them, and should appear as having always been present." Yet behind the smooth harmony of what seems natural must lurk a plan which calls out the brain as well as brawn of the player. "The strategy of the golf course is the soul of the game. The spirit of golf is to dare a hazard, and by negotiating it reap a reward, while he who fears or declines the issue of the carry, has a longer or harder shot for his second, or his second and third on long holes; yet the player who avoids the unwise effort gains advantage over one who tries for more than in him lies, or who fails under the test."

Thomas stresses two points of special interest outside considerations of terrain, strategy, and construction. The first of these is the importance of one-shot holes. Though most lay-outs call for only three or four, Thomas advises at least five. Here one gets a keener interest on the tee-shot than on any other length of hole. "Certainly, a fine test of this type is superior to a poor two-shotter, and, in addition, they usually surpass the two-shotters in character, because ground for them is easily found and they may be made with less trouble and expense." Thomas even urges for congested districts or small private estates the nine-hole course of one-shotters. He ends his book with an admirable sketch-plan for an eighteen-hole course of this sort on a piece of land about three hundred by five hundred yards.

The other point that brings out Thomas's originality and courage is a plan to re-estimate par. He would give putts the value of only half a stroke. This would end the disproportionate value of putting over all other strokes of the game. The man who made two perfect shots to the green and got down in two putts—as allowed by the present par—would defeat the man who made three bad shots to reach the green and then took only one putt. The first would be down in 3, the latter in 3½. Furthermore, Thomas would figure par on short two-shotters as 2½—two regular strokes and one putt—and on short three-shotters as 3½.

It will undoubtedly be many years before any such reform is instituted, but it speaks the scientific mind in Thomas and his close and loving study of the game.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now