Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAnother Ether Wonder

Reporting Further Progress Made by Maurice Martenot Toward Creating Music From Space

ERNEST NEWMAN

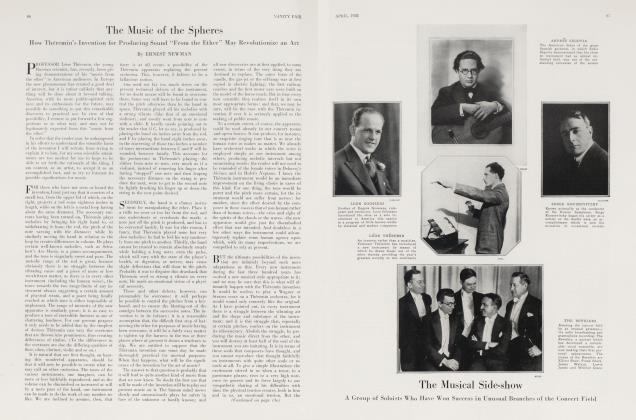

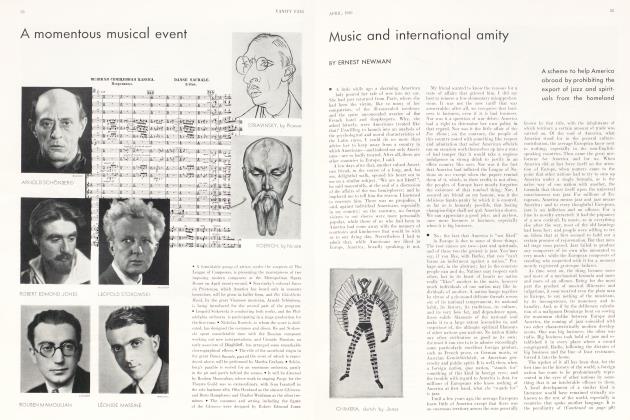

AS Tannhduser said to Elisabeth, "Ein Wunder war's, ein unbegreiflich hohes Wunder." So we said also after witnessing the demonstration in London a few evenings ago of the latest marvel in the way of "music from the ether." Readers of Vanity Fair may remember an article of mine a few months ago, in which I gave an account of the Theremin method of making music by agitating ether waves with the hand, and speculated on the possibilities of the new invention for music as an art. We had hardly ceased talking about M. Theremin when M. Maurice Martenot came along with a still better apparatus.

M. Theremin is a brilliant young scientist who does not claim, I think, to be a musician. M. Martenot is a musician as well as a scientist. He is a young man of thirty-two, who studied in Paris under Andre Gedalge. He always had a bent towards science, and during the war he became a wireless operator. After the war he set to work to turn his experience of wireless to practical musical use, evidently on virtually the same lines as M. Theremin. He is anxious, however, to have it made clear that he owes nothing to his gifted predecessor, who merely happened to be the first to make their common discoveries public; M. Martenot's own apparatus was patented by him as long ago as 1922. He is now, I believe, a professor of music at the Nancy Conservatoire.

What we see on the platform is two wooden boxes that might, so far as external appearances go, be any wireless set. Underneath them are accumulators. As in the case of the Theremin apparatus, I will refrain from attempting to explain the whole rationale of the affair, my knowledge of wireless as a science being merely rudimentary. The scientific reader will be able to surmise for himself the main principles of the apparatus, while the non-scientist would not be much wiser for such explanation as I might give him. In any case, I am concerned here with the affair solely as a musician.

M THEREMIN produced tones of various pitches by bringing one hand nearer to or removing it further from the magic box, while similar movements with the other hand, made in the neighbourhood of a metal coil, produced variations of loudness or softness. M. Martenot alters the frequency of the vibrations by means of a metal wire projecting from one of the boxes; and the instrument is played by approaching or quitting this wire with the hand, on one finger of which is a celluloid thimble connected with the desk; there is further a wooden lever that opens and then shuts off the tone.

In one respect I found the second apparatus, or at any rate the demonstration of it, less interesting than the first. M. Theremin produced a great variety of tone-colours; he not only imitated quite well certain instruments and human voices but gave us hints of all sorts of new instrumental and quasi-vocal timbres that could be drawn from the ether by varying the mutual arrangement of the vibrations. M. Martenot gave us practically nothing of this kind. We may assume, however, that this was only because of the limitations of time imposed on him by the fact that he was one of a number of music hall "turns."

The most immediately striking feature of the Martenot apparatus is the excellent definition of its pitches. It may be recalled that I pointed out a serious defect in this respect in the Theremin system: the pitch being varied by the approach or withdrawal of the hand, it stands to reason that in the process of motion from the point in the air that will produce, let us say, C, to the point that will produce the G above, we hear, more or less faintly, all the intermediate tones. This had two drawbacks. So far as one could gather, the necessity of feeling about cautiously for the correct position of the hand restricted M. Theremin to slow melodies, while between the notes, especially the widelyseparated ones, there was a little upward scoop or downward glide that in the end became rather trying to the musical ear. M. Martenot has something like a keyboard, with a graduated scale, and a pointer indicating the position of the note. The player can actually see, as on the piano, the note to be struck, as it were, though 1 understand that after a little practice this visual aid can be dispensed with, as the pianist dispenses with the sight of the keyboard.

I WAS still conscious of a slight scoop here and there, but it was really very slight indeed, and when it occurred it was probably due to a trifling lapse in technique. M. Martenot played a descending chromatic scale of seven octaves, and the intonation of each semi-tone was beautifully clean. The scale could be theoretically extended ad infinitum in either direction, but in the depths it finally passed, for reasons with which the student of acoustics will be familiar, from the domain of musical tone into that of mere noise, while at the other end the tones would of course go, long before the resources of the apparatus reached their limit, beyond the capacity of the human ear to fix them. M. Martenot certainly proved to us that his instrument is well on the way to being a practical musical proposition: he played a number of pieces on it with not only perfect purity of tone but remarkable technical freedom, producing quite easily such effects as staccato, sudden sharp accents, mordents and other grace notes, trills of the Ukmost, rapidity and delicacy, and brilliant coloratura. If now and then a note was not dead in tune, that was obviously only the accident of the moment. I was not completely convinced that an absolutely steady long slow legato is possible, but in general the sostenuto was remarkably good. M. Martenot could also play much faster than M. Theremin could.

We must make allowance for the fact that the apparatus is still hardly out of its infancy; when this is done, we are bound to recognize that here is something that, with a little further improvement, will be fit for musicmaking on an ambitious scale. The great thing now is to have experiments of a bigger and more exacting kind made with it than presumably have been attempted so far.

In my previous article I pointed out that the progress of music has always been casually bound up with the invention of new instruments or the improvement of old ones, and that one of the reasons for music having become wedged in its present cul-de-sac may be that for the moment we have come to a standstill in this respect. If that be so, the possibilities opened up to music by this tapping of the ether are infinite. With a number of new timbres in which to think, composers would develop new methods of thinking, as they have done in analogous circumstances in the past. But I would emphasize the warning I gave before,—that as quickly as possible composers must get away from the inevitable first mistake of thinking in the new medium precisely as they are used to doing in the old. It may almost be laid down that the first thing to do is to discover not what the etherapparatus can do but what it can not do; and this can be learned only by large-scale experiments by, and before expert musicians. It would be extremely instructive, for example, if, as a beginning, we could hear a string quartet played on four of the Martenot instruments: while some of the effects would be very beautiful, it would at once become evident how much the essence of the music depended on the nature of the strings. When M. Martenot played his descending sevenoctave scale it was instructive to note how the timbre altered as the tone deepened; at times the modification rather resembled that undergone by the flute tone as it descends in the register, but at other times the timbrechanges were purely personal, so to speak, to the ether apparatus. A movement from a string quartet would on the one hand give us the original with a new and intriguing beauty of tone, and on the other hand would show us at a hundred unexpected points the unconscious control of the composer's thinking by the peculiar nature of the strings.

WE must first of all, if the Martenot apparatus is to come to anything, find out not so much its capacities as its limitations. It is hardly a paradox to say that the language of music and the thought of the composer depend less upon what the instrument can do than upon what it cannot do, or only nerves itself to an approximate doing of it under a certain protest; the composer, unable to carry the position by a frontal attack, finds a way round that in the end leads to a greater victory. Some of the best music has been written not only for the instrument but against it. Take the characteristic Chopin idiom, for example. Had the human being had three or four hands, and each hand seven or eight fingers, we should never have had Chopin's music as we now know it. With, say, two left hands and fourteen fingers, bass chords of many notes, with the notes widely spaced, would be quite easy; and piano composers would have written their music with basses of that kind, and with melodies and rhythms that were the natural counterparts of them. But as Chopin had only one left hand, and only five fingers on it, he had to find other means of getting an approximately equivalent effect to that of rich chords widely spaced. This he did by means of the pedal and the arpeggio; he took the disabilities of the instrument (in this case not the piano alone but the piano plus the human hand) and turned them to advantage: and of course the nature of the medium in which he was thus compelled to work had a reflex action on the nature of his thinking. The piano made Chopin as truly as Chopin, in a sense, made the modern piano and its music.

Continued on page 98

Continued from page 67

It is the very smoothness of the ether-wave tone, the feeling it gives that for this instrument difficulties do not exist, the absence of that impression of warfare between the will of man and the will of the instrument on the one hand, and on the other hand between the rival egoisms of air and wood and metal and reed and catgut and so on, ... it is this that makes me suspicious that the peculiar virtue of the new instrument may at first prove more of a liability than an asset. But perhaps only at first. That subtle change in the nature of the timbre to which I have referred in describing M. Martenot's downward scale may have potentialities of its own for the composer of the future; and when he is confronted with a complex of these changes in the process of writing for a combination of the new instruments, some of them with souls of their own that have to be studied and humoured, he may find himself up against a hundred new difficulties the struggle with which will make him thoroughly happy. Alternatively, the smoothness may be ineradicable from the ethertone. In that case also we may get a new music; the very unearthliness, or super-earthliness, of these lovely timbres may call out a spirituality of thought that has hitherto not found expression in music for mere lack of the tones through which it could express itself.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now