Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Novelist's Laboratory

Further Inquiries by the Viennese Philosopher Into the Inner Realities of Ideas and Things

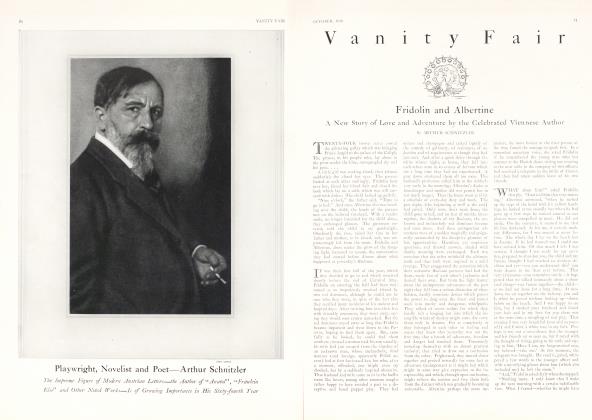

ARTHUR SCHNITZLER

§1

THE Anatomy of Conscience:—Far beneath every action, and never quite comprehensible, there lies something which we dare call guilt. And far above, invisible to our mortal eye, is something which we dare call retribution. Yet the fact that both guilt and retribution do exist is attested by something which is inborn in us and beats unceasingly in time with our hearts—the conscience.

§2

The Genii of Good and Evil:—The purifying power of the truth is so great that the mere struggle to attain it gives rise to a better atmosphere. The destructive power of the lie is so sinister that the mere tendency towards it darkens the sky.

§3

The Dominance of the Negative Sign:—A mixture of uprightness and deceit will produce only deceit, of strength and weakness only weakness, of kindness and malice only malice. For the negative sign alone is decisive; and the difference between algebra and psychology consists in the fact that in the latter two negatives never make a positive.

§4

Three Motives:—Do we ever really want to discover the truth?—No: to prove ourselves right.

To give good advice?—No: to show ourselves the cleverer.

To help people?—No: to redeem ourselves.

§5

A Definition of "Bourgeois :—The bourgeois (or rather, the absurd creature whom modern writers choose to call by that name, and who is also to be found among the proletariat and the nobility) is not characterized by any positive or negative qualities of a special sort, but rather by the fact that the "bourgeois" manages to be as proud of his shortcomings and his vices as of his assets and his virtues. He is always thoroughly at peace with himself, whether he is playing the hypocrite or carrying things to excess.

§6

On Knowing When Not To Think:—It is not the stupid who constitute the worst menace to the welfare of humanity, but the large class of shrewd people who, without actually lying or deceiving, have the happy faculty of permitting lapses in thought when there is some advantage or convenience to be gained by not thinking, much as one switches off a light when he wishes to darken a room.

§7

Infidelity to Self:—Many a person who has abandoned a friend or a mistress, or shirked some obligation, seeks justification in the thought that he is being faithful to himself— a subterfuge which is usually nothing more than a convenient and cowardly kind of selfdeception. For how few of us are well enough acquainted with the laws of our own development to say that such infidelity to a person or a cause will not also entail the gravest injustice to ourselves?

§8

The Geometrical Progression of Hate:—There are few people who, when they have treated a person shabbily, fail to avenge themselves on their victim by another offence, compensating for this second by a third, and so on. Whereby you may imagine how much spite must accumulate in a man who hates you and has not yet found his first opportunity to do you a bad turn.

§9

Some Convenient Exits:—There are many ways of shirking responsibility. There are escape by death, escape by sickness, and finally escape by stupidity. The last is the least dangerous and the most convenient, for even clever people will not as a rule find it so remote as they would prefer to imagine.

§10

The Sliding Scale of Subtlety:—To judge simple people, we need know only the most obvious facts of their existence, their actions and experiences. With persons who are somewhat more highly organized, we must also have a knowledge of their possibilities. But in the case of very complex characters, the possibilities are so manifold, yes, so endless, that action takes on a new significance, for it remains in the end the one possibility which was chosen from among an infinite number.

§11

An Excess of Understanding:—May heaven protect us from too much "understanding". It deprives our anger of its strength, our hatred of its dignity, our vengeance of its satisfaction, and our reminiscences of their delight.

§12

Whether to Adjust One's Life or One's Principles:—There are people who tend to shape their lives in accordance with definite principles—and others who prefer to adjust their principles to the contingencies of their own particular fate. In both cases, all that is involved is an effort to make life as comfortable as possible; while the important thing is to face each new experience without prejudices or assumptions, even at the risk of continual mistakes.

§13

On the Profundity of the Slow-Witted:—Just as there are people who can think more quickly than others, so there are people who will feel, and must feel, more quickly and intensely than others. Such persons will naturally seem more like egoists than those whose emotional life proceeds at a more sluggish pace—just as swifter thinkers are sometimes taken to be superficial, and slow ones to be profound, often without good cause.

§14

Virtue by Proxy:—There are people who are the repositories of all possible virtues with the one reservation that they exemplify all these virtues at the expense of others: they are prodigal of other men's purses, courageous where other men are in danger, and wise with other men's minds.

§15

The Impure Ingredient:—The thoroughly honest man is usually somewhat pedantic, occasionally a bit capricious, and at times even a little malicious, so that one cannot admire his great virtue wholeheartedly. Just as distilled water not only tastes flat but in the long run is not even able to quench the thirst, and does not become completely delectable until it contains several ingredients which are from the chemical standpoint, impurities—so the human character must have something murky mixed with the pure. Some earthy, or even satanic, element must mingle with the heavenly; and similarly that greatest of all virtues, truthfulness, must have its smattering of deceit if the noble quality is not merely to attain an ideal development, but is also to have a fertile effect upon the world.

§16

Guaranteed Until Tested:—There are some persons whom we are inclined to credit with superlative qualities and who never disillusion us so long as we ask nothing of them. Yet they are promptly found wanting as soon as there is some obstacle to be overcome, some duty to be met, some danger to be faced. And they will particularly object to someone who happens, through no ill will but merely by the trend of events, to have put them to the test— quite as if he were the one who bore the real guilt for their inadequacy, since otherwise it would have been noticed by no one, and least of all by themselves.

§17

A Device in Caste Repartee:-If you permit yourself to disparage some class of people, its worst representatives will feel hurt and will try to conceal the fact by accusing you of slandering others whom you had not the slight est intention of attacking.

§18

Original Sin in Ancestors:—It is lucky that our knowledge does not usually extend beyond our parents, or at the most our grandparents. If so much were also known of our more remote forebears, we should not have a single fault nor commit a single disreputable act which we should not attempt to justify as our inherited burden.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 76)

The Three Absolute Virtues:—There are but three absolute virtues: detachment, courage, and the sense of responsibility. Not only do these three in a sense include all the others, but their presence even paralyzes many vices and weaknesses which may happen to form part of the same character.

§19

The Two Kinds of Virtue:—There are relative and absolute virtues. The relatives can be looked upon as the expression of a particular cultural era of mankind, and the absolutes are and will remain a constant at all times and under all circumstances. Relative virtues: piety, physical bravery, chastity. Absolute virtues: love of truth, intellectual courage, and loyalty.

§20

The Fallacies of Remorse and Forgiveness:—Remorse is seldom more than the realization that we obtained something at too high a price. And forgiveness is usually nothing but a fainthearted attempt to restore (even at a sacrifice of justice, honour, and selfrespect) some previous state of affairs which was pleasanter or more beneficial. Thus, remorse and forgiveness merely appear to readjust things—they are either an unconscious self-deception or a deliberate counterfeiting of the emotions.

§21

The Only Development:—Many people believe that they are more developed than they used to be. And of all their qualities, it is their vanity alone to which this illusion really applies.

§22

An Error of Consciousness:—We do not cancel some past stupidity by becoming completely conscious of it. Under some circumstances this can even signify a still greater stupidity.

§23

Intellectual Economy:—When we abandon without false shame some opinion which we have found to be an error, we are using the most wonderful labour-saving device of which the mind is capable—and the one which it least often employs.

§24

The Advantage of Pettiness:—The world is unfortunately so ordered that even the greatest of artists have the full command of their genius only at intervals, whereas the pettiest scoundrels enjoy the complete possession of their wits continually.

§25

A Reasonable Pessimism:—Since mankind as a whole remains a constant, and thus is as questionable at one time as another, just how can we hope for a discriminating posterity when our contemporaries seem so stupid; and

§26 how can we believe in the nobility of the future while the present state of affairs is so unpalatable? The reason lies simply in the fact that malice and sham indignation, those two most basic impulses of human nature, are able to affect contemporaries only. Indeed, there is many an emotion which, when centered upon a living person, would manifest itself as malice or indignation but would be promptly transformed if the person should die, and might even be converted into its opposite. How much cordiality, understanding, and kindness appear suddenly in the hardened and malevolent as soon as there ceases to be the possibility that any other man might enjoy this cordiality and goodness or be able to derive any tangible benefit from it? There is gratification or delight in the thought that someone else is faring badly or has suffered misfortune; there is also the discomfiture or bitterness at the thought that someone is in clover or has met with some experience which he finds pleasant—and such attitudes have much more to do with relationships between individuals, classes and nations than all the friendship, love, gratitude and justice in the world.

§27

Natural Evil in Man:—True detachment, absolute justice, will never be more than an idea. There is a mathematical line, imperceptible to the eye, drawn between severity and gentleness, hate and love, faithfulness and betrayal. But however sure a person may be of his step, he cannot follow this middle course without deviating to one side or the other, and generally to the worse side, since human nature is so made. As a consequence, even when no evil is intended, in his attempt to mete out justice, man decides more often for severity than for gentleness, and is more inclined to repudiate than to sanction—while the renegade represents a much more widely prevalent state of mind than the fanatic.

§28

Asses, Apes and Dogmas:—Not only in religion, but in all other matters, dogma is ready to hand at every moment for the unbeliever. And many a man who derides it one day, is led the next through considerations of politics, advantage, or convenience to champion it as vigorously as though the thought of ridicule and doubt had never occurred to him. And he can rest assured that the pious will always welcome him. even though they have every reason to distrust the genuineness of his conversion.

§29

The Heart of Virtue:—Most good deeds originate in vanity, or in considerations of conscience, or in more or less conscious fears; rarest of all are the good deeds that come straight from the heart. But even these are performed more in our own interest than for the sake of others, since they are nothing but the preliminary payments on an enormous debt which we should never be in a position tc pay off completely.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now