Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowStandardized Golf

How American Methods Have Been Applied to the Game With Several Beneficial Results

BERNARD DARWIN

EVERY month a welcome postman brings to my door several golfing magazines from America. I read them all religiously —from cover to cover—and I am not sure that I do not find the advertisements more seductive and fascinating than anything else. There is for example the gentleman who implies that I am miserably out of date in playing with old-fashioned white golf balls; I ought to be playing with his "oriole-orange" ball or alternately with his "canary-yellow." He gives me a poetical account of it, brilliantly flashing signals to me from far away down the fairway, and tells me that on such a ball as that I should never have any difficulty in keeping my wandering eye. Then there is another gentleman who would like to imprison me in something like a small sheep-pen, so that my body could not lurch this way and that and I should stand still as a rock and swing beautifully. There is yet another who would fasten my two elbows together by a strap so that they would no longer—as I am painfully well aware they do now—stick out at all sorts of prohibitive angles. It is only the fact that I am constitutionally lazy, and that I live three thousand miles away, that has prevented me from sending these ingenious gentlemen varying numbers of dollars with a view to my golfing rebirth.

There is, however, one series of advertisements that "intrigue" me more than any of these. These are the announcements that I have been wasting my time for years (they politely refrain from mentioning that it is over forty years) in learning to swing different sorts of clubs in different ways: what I want is a set of their "matched" clubs and particularly their matched irons, and there are pictures of these sets of clubs, leaning shiny and beautiful against a wall and looking as like one another as so many heavenly twins. I am assured that I am as extinct as the dodo when I exclaim that I am playing my mashie divinely but cannot hit a ball with my midiron. If these two were properly matched it would be impossible for one or other of them thus to turn traitor.

THE people who tell me this are quite diabolically alluring; what is more I have a horrid suspicion that they are right and that I ought to throw away some treasured old friend that is inclined to disagree with the other old friend, the accumulations of years, living in my bag. The more one can simplify or standardize one's game at golf the better— though perhaps also the more dull—it must be and this is one way of doing it.

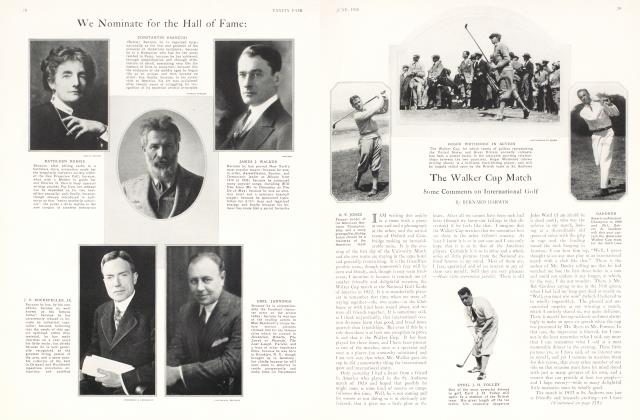

I have often thought this, idly and vaguely, when reading those advertisements, and now I have had it rubbed into me by a very interesting article in one of the Magazines on "British and American methods." I was, moreover, in a suitably humble frame for reading it, because the Magazine arrived almost simultaneously with the news of our utterly crushing defeat in the Walker Cup. About that there is nothing to say but this, that we were beaten by a far better team and that if we had had on our side some players who were unable to make the journey, the margin of defeat might very likely have been diminished, but there could not possibly have been any difference in the total result. I entirely agree with the author of that article, written before the Walker Cup match, that the standard of American Golf is altogether higher than ours, and I am humbly interested in his reasons why this is so.

Several of the reasons, though true, are not new, and I will not go into them here. Of such is the fact that as regards the British professional he has to spend a great deal of his time in club-making or teaching or looking after the green instead of in improving his game; and as regards the amateur that he has not sufficient "desire to perfect himself", that he does not work hard enough at practising and that he often grows slack in thinking only of the match, whereas his American brother is spurred on by the perpetual itch to do a better score.

THAT which was more novel and therefore more interesting was the author's insistence on a radical difference between the two countries in the matter of iron clubs. In effect he said this, that the best American players and teachers have simplified the game, that they have one "standard" swing which is fundamentally the same for all strokes; that on the other hand the British complicate the game and make a very unnecessary mystery of it by laying down that wooden and iron clubs are fundamentally different and that it is almost criminal to play them in the same way. He quotes in support passages from Braid, Duncan, and Harry Vardon, emphasising this supposed difference between wood and iron. He does not quote but I will present him with a saying of a very famous iron player, Mr. Laidlay, which I used to have drummed into my ears when I was younger "The moment you begin to swing an iron you go wrong." He is perfectly right in holding that there has been this difference in teaching, and with all the results of recent Championship and Walker Cup Matches to help him, he has certainly very good grounds for holding that the American view is right and the British is not.

It seems to me, in thinking over the subject, that if we are wrong now it does not follow that we always were so. It may be that we were once right, but are now clinging in our conservative manner to an outworn creed. The gutty ball was a very different kind of ball to control, from the modern rubber core. I do not think that anyone however skilful could have successfully controlled the gutty in a wind by using one "standardized" swing with a number of graded clubs. The ball would have soared away to kingdom come. The modern ball, on the other hand, has an astonishing power of burrowing its undeviating way into a head wind or through a side wind. The great players who taught us a fundamental difference of stroke—a hit rather than a swing—with iron clubs, were by upbringing gutty ball players, and for their own time they were right. Circumstances alter cases and it may very well be that with the modern ball one standardized swing can give more successful results or at least equally successful results with much less difficulty. This is a fact which American teachers, untrammelled by any gutty traditions, have grasped and we have not.

There can be no doubt in the world that when iron clubs first came in they did require a very different manner of playing than did wooden ones. Look at some of the delightful old pictures of delightful old gentlemen in red coats and tall hats. They had a whole set of wooden clubs, graceful, fragile, swannecked, springy-shafted, long-headed, and to begin with, just one iron club and that a ponderous stumpy-headed bludgeon chiefly used for hacking the ball out of sandy ruts. Nobody could have swung that one bludgeon as he did his elegant, graduated, baffing spoons. Moreover, for a long time after iron clubs first became popular, they and their wooden brethren were wonderfully different from one another. As the heads of wooden clubs have grown shorter, their lie less flat, and their shafts stiffer, this gulf between wood and iron has grown very much narrower, but the tradition of the gulf being vast has survived.

1WAS interested in talking over this subject the other day with one of the greatest of the now veteran school of professional golfers, Sandy Herd. He was extracting a certain melancholy satisfaction from the American victory in the Walker Cup, by pointing out that it was essentially a victory for the old Scottish School of golf teaching. The elder Scottish players at St. Andrews, who were the Champions when he was just beginning to try his golfing wings, had the secret of hitting the golf ball; they had, he said, beautiful swings (the word swing as opposed to hit to be underlined) and they had beautiful rhythm such as the American golfers have now. Then he went on to discuss the American iron play and the fact that they swing their irons more than we do. A shot played "from here" (he indicated a half shot) was, he said, very difficult to control and keep straight, but if you could swing the club and swing it a little further back you could keep as straight as a line. Sandy Herd has never, like some of our professionals, been a great writer of books on golf. If he had written one I doubt whether he would have said so much in favour of swinging irons—I fancy the old tradition that it was a wicked thing to do would have been too much for him. That however is pure conjecture. It was at any rate very interesting to hear him expressing the view he did to-day.

If we in Britain have, as it appears, clung too faithfully to an old belief in the matter of irons we seem not to have been faithful enough in the matter of wood. As regards wood, it is the American golfer who has stood in the good old ways and made the true swinging of the driver the be-all and end-all, whereas we have gone worshipping strange gods, and have talked of giving the ball a "hit" or a "punch." Some of us have even been so rash and so foolish as to declare that the follow through is old fashioned and has lost its virtue. If we want to improve, to have some chance of making a fight of it in future Walker Cups, it seems that we must go back to old teaching with our wooden clubs and scrap all our old notions about iron ones.

Continued on page 108

Continued from page 100

Meanwhile though Walker Cups do not personally concern me, there is one of those confoundedly seductive advertisements straight in front of my nose, calling and calling me. I try to take my eye off the page but it will catch the words "This means that you can play every shot with exactly the same swing," and the last four words are printed in italics. Shall I be reckless and plunge? I once knew a man who used periodically to conduct what he called "sovereign hunts" through his wardrobe. As a result of searching in all his trouser pockets he could sometimes find several golden pounds that had been nestling there, and behold there was a little unsuspected treasure which he felt perfectly justified in spending. Shall I go and make a search among my old clothes? I might find some buried gold and then I should be able to buy a whole set of graded irons and live happily ever afterwards.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now