Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGolf for Beginners

A Few Hopeful Words of Advice Addressed to the More Aspiring of the Golfers

BERNARD DARWIN

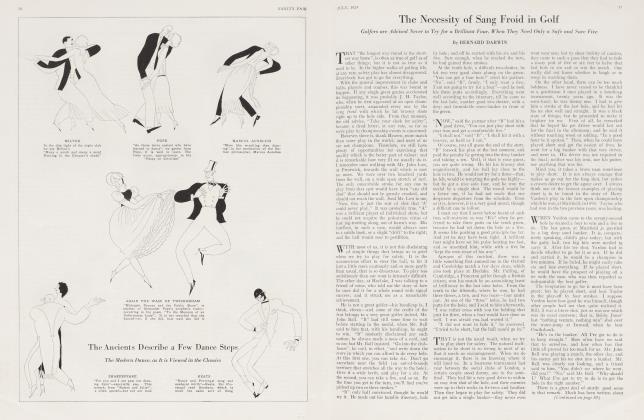

TODAY the term "beginner", as applied to golf players, does not denote a particularly definite class. Indeed I should have thought that there was no such person but for two recent experiences. The first was that of playing behind a gentleman who completely missed the ball three times running and just stirred it at the fourth attempt. He must, I venture to think, have been the genuine article. The second was that I chanced to be in a house with a friend and his wife who had lately, so I heard, "taken up" golf by their two selves. There being nothing to do and his clubs being in the front hall I persuaded him to come out on to the lawn and show me how he played mashie shots. He did so and I am bound to say that I have seldom seen anyone who in a short golfing life had accumulated so many faults. He stood at such a distance from the ball as would have been suitable to a full drive. His left hand was held far under the club with the inevitable result that in the course of the swing his left wrist bent outward in the shape of a bow, as does the wrist of an incompetent lady lawn tennis player dealing with a backhand shot. At the same time he gave a downward tilt of his left shoulder and a jerk of his head in the style employed by Mr. Punch of Punch and Judy when he bangs the policeman with a stick. The result of this was that his right elbow, that most peccant of all golfing members, left his side and flew high into the air. That beginner is not too old. He is strong—keen and has a reasonably good eye. His case is not hopeless and he may yet slough all these faults and hit the ball like a Christian, though scarcely like a champion, but I quote him to show how many faults can be acquired in a short while and how much agony he might have saved himself by beginning under some other eye besides that of his Maker. It is sometimes implied that if we could just play "naturally" we should play properly. Well, here was one who had begun by playing "naturally" and Nature had made a sad mess of the job. Never was I so much impressed by the obvious commonsense of starting in the right way by having lessons.

I USED to have a friend who was intensely interested in the theory of golf and—which is a very different matter—was quite a good golfer. He once told me the story of his one pupil, the perfect beginner. This pupil was little and young and strong: he had never attempted to hit a golf ball in all his life and he put himself unreservedly in my friend's hands. What an opportunity was this for one who loved theories and had in him that latent germ of the pedagogue which lurks in so many of us. Some two or three times a week the pupil was taken to a golf course by the master, like a sheep to the slaughter, and diligently swung and swung his club. A ball he was not even allowed to look at and he was bound by a solemn oath and covenant not so much as to swing the poker or the tongs until the next lesson came round. He was loyal and obedient and came gradually to possess a fine, true, round swing. The weeks had turned into months: still the pupil swung at nothing with perfect docility and at last came the tremendous day when he was to be allowed to swing at a ball. The master teed the ball with anxious fingers, told the pupil as far as possible to disregard it and to swing as he had been taught. Then he awaited the result in trembling hope. The pupil swung easily, smoothly and truly and away sped the ball— as fine a drive as ever was hit.

My story has rather a flat and unsatisfactory ending. The pupil continued to be an excellent driver. He was not so good with his irons, presumably because he studied them under ordinary conditions. "Facts are a great hindrance" one of the most vivid and picturesque of newspaper writers used to remark, and similarly a ball is a great hindrance at golf.

My story may appear more commonplace to American readers than it would to British ones because the American golfing learner is, I think, much more conscientious and patient in wanting to begin by learning the right way and so will submit himself to much more drudgery at the start. Consequently one sees on American courses among the rank and file of players far fewer grotesque and impossible styles than one does here in England. However that may be, if I had a beginner belonging to me I would certainly insist on sending him to a golf school before ever he was allowed to play on a course and I would keep him there as long as possible. I fancy that the mere fact of hitting into a net, which is the dull part of golf schools for the more advanced, is really extremely beneficial, because the learner having the less temptation to look where the ball has gone can concentrate the more on the swing. I know that I can keep my own rebellious body beautifully still when I am only hitting into a net and I imagine this to be a very common human weakness.

IF I had to teach that pupil myself I wonder how and what I should try to teach him. There are those who say that the proper way is to begin with the putt and then work backwards. It seems logical and the most serious objection to it is a practical one, that few beginners are docile enough to submit; they want the thrill of the full drive—I think the putting might come later; it is more of a game within a game; but I should like to try the experiment of starting a beginner on quite short shots. I should try to get it into his head that there is really only one shot in golf. This may not be strictly true but it is much truer than might be supposed from many learned works on golf. I am sure most of us are inclined to think of the golfing stroke as divided up as it were—into too many water-tight compartments. It may be a just criticism of some particular player that he plays his iron clubs too much as if they were wooden ones; it may be true and interesting to note the greater crispness of hitting, the more restrained foot-work, the longer pause at the top and so on, which distinguish the iron play of the champions from their wooden club play. These things are not, I submit, fundamental; they are details, though essential ones when we are talking about the highest class of golf. They do not greatly matter to the beginner. What matters to him most of all is to learn to take his club back in the right way. What that right way is I am not going to try to say but we know it when we see it and it can be learned. Roughly speaking it is the right way for all clubs and if it can once be acquired it is like the art of swimming and cannot be wholly forgotten. I imagine that it is most readily acquired with a fairly short club and in playing a fairly short shot and so I think I would start my pupil, after as much swinging at the empty air as he could reasonably endure, playing quite short shots with, let us say, a mid-iron, then I would gradually make him extend his swing. If he really got ground into him the rudiments of swinging that iron truly, I cannot believe that he would not soon learn to make the necessary adaptations in the case of wooden clubs. The finer shades of distinction could be cultivated later.

In re-reading what I have written I notice that I said "take his club back in the right way." That was wrong of me—I should have said "swing his club back in the right way" and "swing" should have been put in italics. It is to my mind hardly possible to overemphasize the word "swing" and the less we use any other word, no matter what shot we are talking about, the better for us. Compared with such words as "hit" it implies a disregard of the ball and one of the great dangers in golf is that of becoming "ball-shy" and flinching during the stroke.

Some years ago a friend of mine at Hoylake asked the great Mr. John Ball to teach him to play pitches. Mr. Ball set him to work playing at first the very tiniest of shots but, no matter how short the shot, he insisted that the learner's left knee must move. In other words he made his pupil swing, it might be ever so little but still swing, if it were only to loft the ball from one side of a flower-bed to the other. I am sure he was right and so my hypothetical pupil playing his little midiron shots should not just stand still and tap them, if I had sufficient force of character to prevent him.

If his left wrist bent in a bow, as did that of my poor practiser upon the lawn, what should I do to him? When I have tried to teach my own relations, not with any conspicuous success, I have always in that particular case used the analogy of the backhand stroke at lawn tennis. I have bent my own wrist as preposterously as I can and said "Now, would you play a shot at tennis like that?" I have then told them to imagine themselves playing a left-handed backhanded shot and it generally has some effect. I said it to my practiser and he hit a couple of excellent shots with a left wrist that would have done anyone credit and then relapsed and we had to go in to tea. I wonder what his wrist is doing now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now