Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe New Metropolitan Takes Shape

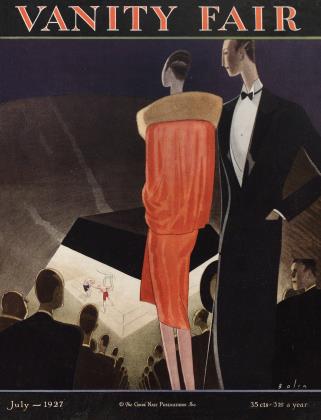

Problems and Opportunities to Test the Architects of New York's Impending Opera House

KENNETH MACGOWAN

THE building of a new opera house is the event of a generation in any European capital. It calls for wise and varied counsel and much public discussion. The site, the style, the seating arrangements, the stage appointments are all matters for very serious consideration in the light of the architectural and theatrical progress of the past years.

New opera houses may seem a little less important in a land where skyscrapers leap cloud-ward over night. Yet a considerable circle of New Yorkers, in addition to the thirty-five parterre boxholders, are interested in what form the New York's new Metropolitan Opera House is likely to take when Mr. Otto H. Kahn and his associates open it to the public in 1929. Seven thousand subscribers are wondering, for one thing, if the traffic situation will be remedied, and a miscellaneous public of fifty or sixty thousand is hoping to have a slightly less awkward view of the stage than they presently enjoy from the side balconies of the old house. A very few may even be discussing the progress in the philosophy of theatre construction that the last quarter century has brought forth and how it may be reflected in the new house.

One thing the public may he sure of —the new Metropolitan will be very different from the old. The "Met"—pet name combining affection and exasperation—was built in 1883. Too much social and aesthetic water has run under the bridges of the East River to leave either its gaudy decoration or its oldfashioned tiers of towering balconies intact. The names of the architects associated in the work on the new opera house should be evidence enough. Benjamin Wistar Morris, designer of the Cunard Building and the additions to the Morgan Library, has given plenty of evidence that he is far from wedded to the age of gilt and red plush. Joseph Urban, architect of theatres in New York and Florida, as well as stage designer, knows at first hand the progress that Europe has made in the construction of its theatres and auditoriums.

The opportunities presented to the architects are extraordinary. The restrictions are few and some of these seem likely to disappear. At first the opera authorities were in favour of the idea of nestling the auditorium and the stage in the lower stories of an apartment house-studio building to tower three or four hundred feet in air. Now general opinion around the Metropolitan banishes the tower on account of the difficulties with the fire regulations. This should be secondly to the advantage of the new building. It can now have an outward form significant of the theatre and of nothing else. The foyers, the auditorium, and the stage house can now give proper outer evidence of their existence.

The plot of ground selected is wholly admirable. On one side is the two-way thoroughfare of Fifty-seventh Street; on the other, east-bound Fifty-sixth. The plot is not on a corner—a disadvantage; but it is thirty to forty percent larger than the old site. Working with this land on these particular streets and even taking into account the zoning restrictions, a building of ten to fifteen stories is possible.

The stage will be on a magnificent scale. There is room on it for an acting space fully double what the opera now has. Instead of a width of about a hundred feet, the stage will have somewhere in the neighbourhood of a hundred and fifty. It can easily be made a hundred feet deep without crowding the auditorium, so long as the rear part of this stage is recessed under a paint .bridge, a storehouse or whatever space for property master and electrician are required. This Hinterbühne of the Germans—a stage as big as our normal Broadway stages hut restricted in height — would thus provide a fine vista for any unusually deep scenes.

The electrical equipment is sure to match the largest stage in America. The mechanical devices dial nun he installed for scene shifting will doubtless be much affected by the nature of the productions now owned by the Metropolitan. The revolving stage is impossible on ibis score. Space is available for sliding stages, though they themselves are expensive. Whatever mechanical equipment is finally provided, the house should have one or more of those movable canvas skies which Max Hasait of the Dresden State Opera House has perfected. These wrinkle less cycloramns run on semi-circular tracks overhead and roll up in less than a minute on gigantic spools at the side of the proscenium. They are indispensable, and the Metropolitan might well utilize the scheme which I saw in plans drawn by Hasait for Reinhardt's Festspielhaus in Salzburg. This called for a nest of three or lour of these cycloramas concentrically arranged and varying in size from half-stage to full-stage depth.

Vastly improved technical equipment of one sort or another may he confidently looked for in the new building. It is the treatment of the auditorium and the seating arrangements that will test the new house and its architects.

The architects have been given two conditions that must determine their treatment of these problems. They must provide room for 5000 spectators instead of 4000 as in the old Metropolitan. And they must arrange for a single row of thirty-five parterre boxes. It is here that real dilfficulties and real opportunities present themselves. And it is here that a little knowledge of t he historic. development of theatre auditoriums and the philosophy behind this becomes necessary.

(Continued on page 88)

(Continued from page 61)

When the ducal palaces of Italy were first turned into theatres in the sixteenth century for the performance of court masques the form of the opera house was established which lasted through four centuries. This, the aristocratic auditorium, was simply a great oblong room with horseshoes of shallow balconies rising tier on tier to the ceiling. The result was a splendid auditorium for the display of court and courtiers in towering boxes. But only those seated on the floor of the auditorium or in the centre portions of the balconies had a clear view of the stage. It is this type of auditorium which was perpetuated in the court theatres and opera houses of aristocratic Europe until German architectural reform came in with the advent of Wagner. The Metropolitan was one of the last important opera houses to he built upon these antiquated lines.

The architect Semper and the producer Wagner provided a new type of theatre in Bayreuth. Their theory was that all the spectators should be seated on a steeply slanting floor in a sort of arena arrangement. Every one should have a clear view over the heads of those in front. There should be no overhanging balconies; for these raised the spectators too far above the proscenium opening to get a good view of all the stage.

It would he an aesthetic crime of the first degree if the new Metropolitan turned out to be nothing but a repetition of the old so far as the arrangement of boxes and balconies goes. It is a little too much to hope for a thoroughly radical and nearly perfect auditorium. But it is easy to see a possible compromise between the aristocratic auditorium of the old court theatres and the democratic auditorium of Semper and Littmann. Retaining the thirty-five parterre boxes and providing five thousand seats make a compromise necessary.

One thing is simple—the orchestra floor. The architects will undoubtedly provide a well-graded parquet seating as many as at present, about twelve hundred. With the placing of the boxes, the compromise begins. By giving the whole house a bold fan-shape, after the Wagner model—perhaps it might better be compared to the hell of a trumpet—the boxes can all be accommodated in a broad half-circle behind and immediately above the orchestra. By substituting this curve for the horseshoe of the old house, the architects can bring the boxes at the rear a dozen feet nearer the stage.

To be sure, the whole,circle of boxes would then face the stage instead of each other, and there may he box holders who imagine that opera is a device for their self-display. But there is considerable evidence that the newer generation of well-to-do America is taking its opera as an aesthetic, as well as a social, experience. The new house is to be built neither for the past nor for the present alone, but for the opera audience of the next three generations, and nothing must stand in the way.

To continue with the seating arrangements that an intelligent compromise will provide, the orchestra circle rises from immediately over the boxes hut will not extend far to right and left. This arrangement, which the German theatre authority, Fuchs, suggested fifteen years ago for the ideal auditorium, would provide a kind of terraced orchestra, with the boxes in the face of the step-up. Above the orchestra circle and still well to the centre and recessed in the rear wall of the main auditorium would come two balconies of sufficient capacity to provide the total number of seats desired.

The advantage of an arrangement of this sort is that even the cheapest of the extra thousand seats are better located as to sight-lines, because they are directly in the centre instead of hanging on the side walls. No one is appreciably farther from the stage than in the old house. If these balconies were brought forward over the orchestra as in the smaller Broadway theatres, their slant would have to be increased past the legal scale, or their capacity reduced below that required by the opera house authorities.

The aesthetic profit in such a compromise is that the auditorium is still left clear as a whole for a unified architectonic treatment perceptible to all the spectators in the main body of the house. What this treatment may be remains for the architects to work out. In similar fashion the exterior and its decorative detail are still in flux. Yet the proportions and the arrangement of the interior must influence and be reflected in the outer building if the exterior is to have an interesting and significant quality. Decoration may be wrapping paper, and the seating arrangement and the stage space are, after all, certainly of paramount importance; but the mass of the exterior may speak of the modern, well-conceived house within, or—worse luck—it may not.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now