Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Truth About Dining Out

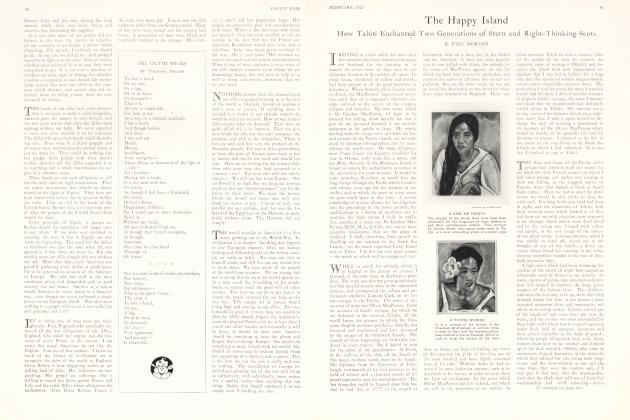

GEOFFREY KERR

With Some Hints on How to Avoid it and a Recital of Its Principal Horrors

MANY of the more dismal features of present day life are due directly to the march of science. If sleeping cars had never been constructed, we should not have to sleep on them; if motor cars had not been invented, we should never have to park them. Our forebears were not awakened by telephones and steam riveters.

In respect to social obligations, however, we have really changed but little. Even the cabaret is not a strictly modern curse, while the Evil which we propose to examine in this article had its origin in the Garden of Eden. For Adam and Eve were unquestionably the first diners out, just as Eve was unquestionably the first lady whb tried to reduce by putting herself on a fruit diet.

Dining out in olden times is supposed to have been rather fun. But such a belief argues a great lack of imagination. The "tired business man" is not a modern product; how much more tired he must have been in palaeolithic times, when his business was slaying large wild beasts with a blunt stone axe. The business man of today who returns from Wall Street after hours of wrestling with bulls and bears to find that he must instantly change his clothes, leave his comfortable apartment and dine with some people whom he greatly dislikes, is naturally annoyed; but his annoyance can be as nothing to the fury of a stone-age gentleman, actually bringing his bear home with him, only to be told that he must change his skin, leave his comfortable cave and go off to share a neighbour's boar. However, our stone-age friend had one advantage over our contemporary: he could use the implement that slew the bear as an effective counter-argument on his wife.

DINING out was probably at its worst during just those periods when it is supposed to have been most amusing. It is doubtful if the Roman hostesses enjoyed themselves so very much. The modern housekeeper, complaining to her husband about the man he has invited for dinner, would cease her complaints if she paused to reflect that, living in ancient Rome, he might have brought home Lucullus.

A word as to the banquets of the early Italian Renaissance. The Borgias were obviously not ideal hosts. And the man who shrinks today, under the ordeal of an official dinner with the president of his corporation, should comfort himself with the thought that the wine, at least, will not have been intentionally poisoned.

Dining out today is as huge a dud as ever, though there are, of course, occasions when it may be almost pleasant. Thus, you may be in love with your hostess, or you may be very hungry. One man who really enjoyed dining out did so by the simple process of starving himself for twenty-four hours beforehand. When he took his place at table, with the other victims at the sacrifice, he was unconscious of anything but that he was at last to find himself face to face with food. He therefore had a pretty good time; but he was little help to his fellow-guests—and less than none to his hostess. Such self control would have been better devoted to a rigid determination never to dine out at all.

It is not proposed here to discuss the public banquet or the large dinner party; the mere thought of either of these revels fills the normal mind with too much dismay. The simple fact is that any meal away from home is liable to be unpleasant—from the rubber sandwich one chews on for hours under the impression that one is having a "quick lunch" to the "pot luck" dinner which you get when an invitation to "drop in for a cocktail" has been vastly overstayed. "Pot luck" is usually no luck.

The normal invitation to dinner is hurled over the telephone at some hour, like nine o'clock in the morning, when to deny your presence would be ridiculous. You are therefore forced to conduct the conversation in person and a refusal becomes difficult, if the inviter knows how far ahead your faculty for inventing "dates" is likely to carry you. However, it is not impossible, except to invitations of the "any-Thwsday-this-year" order. Such invitations as these can only be avoided by secret emigration.

It is unwise to try to make up excuses on the spur of the moment; the spur is too sharp —and the hour too early—for really inspired invention. The best plan is to keep a "disengagement-book". This resembles an ordinary engagement-book, except that, early in the year an afternoon is spent in filling its pages with imaginary engagements—lunches, teas, cocktail parties, dinners, theatre parties and suppers. Armed with such a book, you can continue to refuse any invitation ad infinitum; and if your would-be hostess, when you arc refusing to engage yourself for three months ahead, doubts your sincerity and asks for details, these can be forthcoming in such instant abundance that she must be completely convinced both of your truth and of your popularity. Indeed, she is likely to be so excited by what she thinks is the latter that she will redouble her efforts to secure you and you may have to spend whole days at the telephone, reading out extracts from the book to her. Like all good ideas, this one should be worked with moderation.

We will suppose that the wretched invitee, lacking such an accessory as a disengagementbook, or knowing no better, has got enmeshed and has engaged himself to dine with Mr. and Mrs. Eaton on Thursday week. He spends much of the interim in trying to think of a good excuse for getting out of it. This is a sheer waste of time, for there is no such thing. No reason for refusing a dinner invitation, once accepted, carries the slightest conviction unless it is accompanied by the announcement of one's demise.

ON THE Thursday in question our Mr. Smith awakens with the thought, "Oh, God, I'm dining with those people tonight!" Three other people wake with the same thought, "Oh, God, I'm dining with those people tonight!" while Mr. and Mrs. Eaton wake with the thought, "Oh, God, those people are dining with us tonight!"

Making a careful note of the address, Mr. Smith finishes dressing and goes out to find a taxi. At some point during the drive of doom he begins to say to himself, "Is it 60 East 61 St or is it 61 East 60th? Or is it West 60th?" He returns home to learn the truth of the matter only to find that the piece of paper with the address on it has been in his pocket all the time. This makes him late, by twenty-five minutes.

When he arrives, the party is all assembled, and waiting for him, every face gaunt with boredom. The host'and hostess will cither have served cocktails to kill the time, in which case the three other guests will have what is technically known as a "lead" and the host is liable to punish Mr. Smith for his unpunctuality by not giving him one; or they will have decided to wait till he comes, in which case the three sufferers will look a little extra gaunt through fear that there are to be no cocktails.

There are two kinds of prohibition cocktail—the gin and lemon variety, which tastes like sulphuric acid; and what is supposed to be a dry Martini, which tastes like a concentrated solution of quinine. Either kind should be regarded as purely medicinal and swallowed at one gulp.

(Continued on page 110)

(Continued from page 67)

Mr. Smith bravely disposes of his medicine and then glances at the tall lady by whom he is standing. Her name, as far as he could understand it when the introduction was made, is "Miss Bubble"; and her appearance he instinctively dislikes. He is very tired and longs to sit down, but everyone else is standing; his knees begin to sag slightly, as part of the energy needed for their full support is given to the task of conversing with Miss Bubble. She tells him a vivacious story about nothing at all, and he replies with suitable ejaculations of "Oh!"

The other two guests are apparently called Tootle. They are a married couple with whom Mr. and Mrs. Eaton foolishly dined a week ago, their presence tonight being the awful but inevitable result of that festival. Mr. Tootle starts to tell a golf story and, just as he is about to reach the point, dinner is announced and the sextette passes into the torture chamber.

The menu on these occasions is usually chosen to provide a maximum of trouble with a minimum of nutrition. Thus, Mr. Smith finds that the soup contains vermicelli so long and wiry that when pursued with the spoon it suddenly becomes alive; the butter is so frozen that it is as "spreadable" as marble; the rolls could explode no more violently if they contained dynamite. The soup is followed by an amorphous dish containing a great variety of crabs' tendons. On the inconvenience of this dish it is unnecessary to expatiate, but it has one virtue at least,—conversation, during the eating of it, is rendered impossible.

With the next course talk is resumed and, while Mr. Smith regrets his lack of the surgical skill with which to do justice to a squab, prohibition is authoritatively made responsible for the crime wave and Miss Bubble tries to relate the plot of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Then comes an awful moment when it looks as though Mrs. Tootle is going to describe her last operation. She is, very luckily, interrupted by the arrival of the salad, on which the cook has expended the last ounce of her genius for making things difficult. It consists of several thousand cubes of polychromatic vegetables.

After dinner, Mr. Smith rashly accepts a cigar. It carries out the usual Eaton "dry" principle. In fact, it is so dry that, as he grasps it, the wrapper flies off in all directions. This renders it quite unlightable, which is probably a fortunate circumstance. However, there is one splendid thing about any cigar at any dinner; it is a sign that dinner is over.

After the coffee, which might have been excellent if it had been hot, Mr. Tootle tells several more golf stories describing some of his recent rounds quite minutely; Miss Bubble sensibly refuses an invitation to sing and then the Tootles and the Eatons sit down to play bridge. Mr. Smith and Miss Bubble sit down to watch them. It is a pity that their hatred for one another has by now assumed such gigantic proportions that they can derive no enjoyment from the difference in manners exhibited by each gentleman, according as to whether the lady playing opposite him is his wife—or the other man's.

So, the evening drags on until alcoholic refreshments are brought in. Mr. Smith, if he is wise, will refuse any such refreshment. A careful examination of statistics would probably show us that many marriages, so far from being made in Heaven, have been the direct outcome of a high-ball after a dinner party.

Again, if Mr. Smith takes a drink he is likely, in spite of all that has happened, to be suffused with a feeling of friendliness. Under the influence of that feeling, his better judgment may be so far submerged that he will agree to "go on somewhere" with them.

Or a high-ball may even lead our poor, misguided young friend to enter into some kind of future social contract with Miss Bubble, from whom, after such a beginning, there will be no escape. No! The guest at a New York dinner party will, if he is wise, vanish at the earliest possible moment, drive straight to the nearest Childs' and order a dish of bacon and eggs.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now