Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIrrision

A Sardonic Tale Involving the Capture, and Loss, of a Man's Love

RUPERT HUGHES

REGINA put the poison in his coffee because she could endure his love no longer, his all-enduring patience, his invariable forgiveness in advance, like a paidup indulgence, absolving her of everything.

As if to increase her impatience, her husband raised his coffee to his lips and drank her health, with that infernal and eternal waxeneyed gaze of his, saying:

"They used to toss off a stirrup-cup before they rode away: this is my subway-cup, O best of wives!"

She smiled extravagantly. She could afford a smile, since it would be the last she would ever have to bestow upon him.

Her smile became fixed as she waited for the venom to take effect and make a widow of her.

But he did not start. He did not writhe. He drained his cup, laid his napkin by his plate and rose with the same old refrain:

"The best of friends must part: I'll be home for dinner."

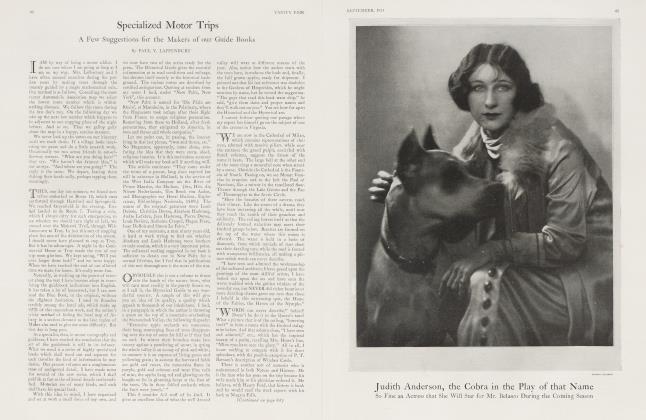

As he advanced to kiss her, she thought of him as a cobra come to stalk her. He did not fall at her feet, nor across her lap. He bent to kiss her. She would as lief a cobra tapped her mouth.

BUT the poison, which he did not taste, blistered henown lips. He did not heed the shudder of pain and dread that ran through her, but crossed the room with a terrifyingly steady step.

He turned and blew her a kiss across his palm, and vanished. She heard the elevator door open and clang behind him.

She ran to the window, her mouth throbbing. She must see him drop. He looked up and waved her another kiss. A taxicab just grazed him, but he did not waver. He hurried down the street, swinging his cane with the cheer of a contented man who leaves his home to win comforts for his loving and beloved wife.

But Regina whirled and ran about the room, her lips scared and swollen. She put oil on them to quench their fever. Her mirror reflected an image of thwarted horror; a mouth bloated and terrifying.

All day she ached, not daring to sec that other man, that nearer man, her lover. She waited for the telephone to announce her husband's death. Messages of all sorts came, but never the one she waited for.

At last her husband's voice came over the wire. He had won a business victory of such importance that he was certain to be rich at last. They could travel the world over together. He would neglect her no more—he who had maddened her by his devotion! He could now give up his business and spend all of his time with her.

"Isn't it wonderful?" he asked.

"Yell, yell! oo-onder-wool!" she mumbled with her monstrous lips.

"I'll be home early, my angel!"

She hung up the receiver on the hook in a violent rage.

When he reached home, she could not hide her wounded lips. He groaned with pity:

"You burned the most beautiful mouth in the world, you poor sweet! How? How?"

If only he would spare her one grain of his insufferable tenderness!

She w'as too busy with her own distress to plot against him further. She wanted her lips to become normal again. Even as they were, they were eager to meet her lover's.

One evening, after dinner, as her husband sank into his chair with that same ancient groan of satisfaction in his home and in her, she w'as swept by another frenzy and stole up behind him with a naked dagger in her hand.

As he leaned forward to reach for his evening paper, she let the dagger drive, plunging the blade at his back.

The steel shaft turned aside from the cloth of his coat. But it glanced into her ow'n side, slashing the silk of her gowm, making a little red gash in the flesh. It had almost reached her heart before she could check it.

Blood showed on her breast as she drooped to the rug.

She barely escaped falling on the knife. She wished she had not escaped it.

Again his sympathy! Again his loving words, his agonies on her account, his incredible tactfulness.

For a long time her marmoreal bosom was a torture to her wfith its scar and its eternal bandages; but her husband never failed to feed her with praise and with pity.

SHE could not tell him how she came by her wound. He never suspected anything like deceit in her explanation that she had stumbled over the train of her evening gown.

As soon as she was well again, they set forth on their travels, the long dreams of his life, the fulfillment of his ideal of complete fidelity to her. Now she had no respite from him. The farther she went from her lover, the more she hated her husband.

One day, in a far city, she stole out and bought a pistol.

She bought it for protection, she said. She meant it. She wras desperately eager for protection from this paragon of perfection.

One day, as he took her in a motor-car for a drive in the country, she expressed a whim to alight, load her pistol and practise with it at a target. Her whims were always his law. Against a rock in a forest he fastened a bit of newspaper. To make sure that the w'eapon was a reliable one, he fired the first shot. He hit the center of the paper, handed the pistol to her and w'ent forward to put paper over the rent which his bullet had made. She seized the chance and, aiming directly at him, pulled the trigger. The bullet glanced from his shoulder, struck a rock, made a ricochet and came back at her. The w'hine of it was like the voice of a fiend.

She flung her head aside in horror as the bullet ripped across her cheek and rent the volute of her ear.

Remembering his experiences as a soldier, he set his thumb on the nearest arterial center to keep the .blood from draining her life away. Holding her so, he lifted her with his free arm, astounding her even in her dismay by his swift strength. He sped with her to the car and managed to start and steer it while he held her body in his right arm and kept his thumb at the base of her throat.

He drove the car at full speed across the hills, down the plunging steeps, up winding heights. Faint as she was, she marveled at his caution and his audacity. He managed, with her body, to steady the wheel a little when he shifted the gears or set the hand-brake.

In the country the task was difficult enough. In the city it was almost impossible, yet he managed it all adroitly.

THERE was something godlike or demoniac in the genius with which he selected the lesser risks. It seemed at times that he must choose between killing her by delay or killing some stupefied child that paused in the road and stared aghast at the speeding motor. But he evaded every danger.

He was afraid of nothing but the loss of her; and this fact amazed her, for he had previously seemed but a weakling, a sort of human limpet. Now she saw him as a warrior compelling Fate. Now that her very life depended on his saving of a few seconds, she saw in him a sort of god-like divinity.

The love for him that had once thrilled her came back on rushing wings. Her husband rose, in her fancy, from the heaped-up fagots of the years like a martyr's Soul ascending from the flames.

He gained the hospital, drew up safely under its portico, checked his car, gathered her in his arms and carried her in.

The attendants at the hospital were not much moved by his distress, but he commanded them as if they were her slaves. He ordered a surgeon and demanded immediate action.

He explained that he had fired his pistol by accident and almost killed his wife.

After a few days, Regina was pronounced out of danger.

And now anything the man did or was. seemed miraculous and precious to her. His devotion seemed to her like the stooping of an angel. A new fire burned in her soul.

But something seemed to have broken in the soul of the man, for now it was his hand that first relaxed when their hands clasped. It was his lips that wearied first of kisses. Unaccountably, he fell asleep as he kept vigil over her. It was now his turn to burn with fever.

And then she grew well. The scar across her check was hardly more than a whiplash that added a fresh interest to her wild beauty. Her ear would never be perfect, but a strand or two of her hair helped to conceal it.

When he took her home from the hospital, he was a desperately sick man. His fever increased. The next morning it was he that was in danger. It was she that lavished tenderness and words of love.

Continued on page 78

Continued, from page 30

He did not put her hands away or distrust her eyes, as well he might, hut he let her fingers fall from his, and his eyelids drooped heavily between her gaze and his.

Her knees were constantly on the floor, in prayers of remorse, prayers which she dared not let him overhear. He fell asleep as she prayed for him and for the salvation of her own abominable soul.

Then there grew up in her heart the fear that it was her love for her husband that was killing him.

Her lover returned to seek her. She would not see him. When he tried to force himself into her presence, she struck him with her hand.

When he had gone, she was seized by a mad fancy that, if she were to call him back and kiss him, she could punish him and save her husband.

But she could not unlove her husband now, though she saw that her love was drowning him slowly. The more she loved him the more he died. What her hate had been unable to achieve, with all its weapons, her love was accomplishing without aid. There was a sardonic note in her punishment.

Yet, fatal as she knew her love had become in its resurrection, she could not cease to cling to him. She could not withhold her lips from his cheek though they seemed to draw the very life-blood from them. His strength seeped out swiftly. Then, as her love intensified into something fierce and strange, and became all fire and passion, she destroyed him utterly.

And so, frenzied, shrieking defiances and appeals at high heaven, holding him more and more straitly to her breast and away from the clutching hands of death, she realized, at last, that she clasped but an empty alembic of clay, white, cold and dead.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now