Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe French Occupation of New York

Sacha Guitry and His Compatriots Are Beginning to Make Broadway Resemble the Ruhr Valley

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

THOSE of us who, from time to time, graciously share our wisdom with the lords of the American theater, appear to be just wasting our time. We no sooner make it quite clear that it is virtually impossible to lift a play from one language to another and that it is especially difficult to transport one from Paris to New York without spilling, than they retort incorrigibly by devoting one Spring week to three productions from overseas and all three from Paris. During this week in which the French quota of dramatic immigration was exceeded, a week already sufficiently marked in the calendar by the most depressing day of the year (March 15th), Broadway looked for all the world like the Ruhr Valley.

Of the three, only two, to his probable annoyance, were by Sacha Guitry. The other, which should have been called Adrienne Can Be Had was known as Pour Avoir Adrienne in Paris, where it was written and acted by Sarah Bernhardt's grandson. But the younger Guitry scored two out of a possible three.

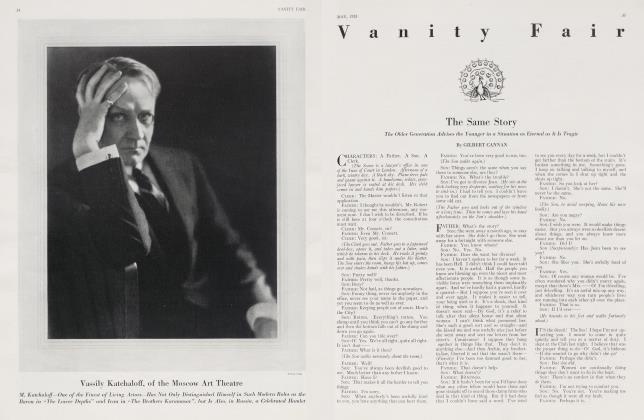

He is a tall, soft, stoutish comedian, with a disposition to sentimental tears constantly corrected by a buoyant wit. For all that he was born in Russia when the folks were on tour, he is the most Parisian of them all. You would not be far astray if you thought of him as the George M. Cohan of Paris, a wise, zestful child of the French theater who can write plays as fast as his pretty wife and his magnificent father can act them, comedies as redolent of the boulevards as Cohan's are of Broadway, sprightly pieces which are fish as far out of water in America as would be Sept Clefs pour Baldpate if you were to encounter that farce in the handsome theater which stands at the curve of the rue Edouard VII in Paris.

The Interpreters' Corps

OF the two recent Guitry productions in New York, the less characteristic and the more translatable and interesting was his Pasteur, a dramatic biography written by the younger Guitry during the war as a play which, in its glorification of the great French scientist, would soothe those compatriots still ruffled by the annoying German boasts about their scientists and which, also, would provide a role not at odds with the advancing years and expanding bulk of the great Lucien Guitry. In New York the role was assumed by Henry Miller, who had it in him to suggest that here on the Empire's stage was just such a great man as Louis Pasteur must have been. The shift to English was managed by the best of our Interpreters' Corps, Arthur Hornblow, Jr., and it was not his fault if, like most historical plays, this one betrayed at times a certain artless self-consciousness. You know the kind. They begin with two negligible characters—a valet, perhaps, and a chambermaid—conversing as follows:

"Well, if it isn't 1870, the year of the Fran co-Prussian War!"

"True, true. How unfortunate if this purposeless slaughter should interrupt the work of that great scientist, who is forty-three years old and is even now at work in his laboratory, undiscouraged by the petty enmities of the academicians and determined to save humanity with his serum cure for rabies. Strange is it not, that we should have been speaking of him for here he comes now."

Pasteur does not belong in quite this clumsy category, but there are touches of this sort of dialogue in all its earlier scenes. The translation is flawless, for, unlike so many of the men engaged for this work along Broadway, the younger Hornblow not only knows the French language (which is a help, of course) but is also reasonably familiar with English. But there are scripts of Guitry's which even he would find elusive. There is, for instance, this Une petite main qui se place which David Belasco has bought for use when he gets around to it. Not only is its very title untranslatable but there are whole scenes which, done into English, would take on a coarsegrained vulgarity which is somehow not in them in the French text as spoken by French players before a Parisian audience.

Consider for the moment the scene where the wounded professorial cuckold (played by the younger Guitry himself) is glowing with recovered pride in the discovery that at least the pretty housemaid loves him. She is serving him his breakfast and though they are going to fly together that night, she is still the humble handmaiden shifting from foot to foot in his benign but magnificent presence. Across his chocolate pot he puts her through an examination. Where does she come from? From the country? How charming? The country is so nice. And what does she like? Eating? Yes, eating is fun. And wine? And music? Yes, music is nice if it's not too near. And she likes to walk? And to dance? And to-He begins to choke and grow flustered. Was she—but, then, of course not—she couldn't be—he makes a dozen running at that question before he asks it. Was she a virgin? "But yes", she answers and then at the look of astonishment on his face, she hastens to add: "Oughtn't I to be?" At such trustful innocence he is completely overcome. Fie really has to get up and wipe his glasses and pat her confiding hands. "My poor dear child", he murmurs in a fatherly way. "Of course, of course. What must you think of me? Besides", he adds cheerfully. "We can fix that."

It is such Guitry scenes as this one which are either lost in mid-Atlantic or which, when they emerge bluntly on the American stage, make you wish they had been.

Both Pasteur, which Henry Miller undertook, and The Comedian, which Belasco entrusted to Lionel At will, were written for Lucien Guitry, as able a player as we have ever seen anywhere in the world. The central roles were conditioned by his son's knowledge of the great actor who would play them his intimate knowledge of the rich resources of one who, after all, is in his sixties and who, to put it bluntly, is fat. Lucien Guitry's calves, as they emerge majestically in the silken hose of Le Misanthrope are the largest supporting the drama anywhere in the world. The memory of them embittered our lesser Arnold Daly when several of the reviewers mentioned in passing that he was a trifle bulky for the role of the mad lad in The Tavern. In an article which, oddly enough, was printed in The Bookman Daly exploded. "Are they judging actors by weight, now?" And, giving some crushing figure as Guitry's weight, asked rhetorically if the Parisian critics ever thought it mete to mention it in their comments on his performances. To which question there are several answers, one covering the suspect gentleness of most Parisian critics in general and one speculating idly on what even they would say if the elder Guitry ventured to play Puck or Peter Pan. As a matter of fact, it has been years since he has stepped before his adoring Paris in any role that had not been made to his measure as exactly and considerately as your new Summer flannels, sir, were made for you. When one of these discarded suits was brought over and draped on Lionel Atwill the other day, the fit was not conspicuously close.

Judging By Weight

AS a matter of fact, even in New York, the reviewers are flagrantly silent on the matter of sheer girth. Several of our actress are strong on technique but weak in their resistance to carbohydrates. Just before a New York première, they may take to a diet of prunes but often too late. Yet it. is seldom that the chivalrous scribes will record the anguish of the audience. They may go so far as to suggest that the charms of the star were a trifle mature for the slip of a girl she was supposed to embody, but they seldom let the word "fat" take its legitimate place in dramatic criticism. Not long ago, when the inappropriate bulk of one of our players was but partially concealed by a nicely calculated looseness of costume, we were enlivened by the comment that floated back to us from two writers who were indulging in one of those piercing staccato conversations which people fondly imagine are whispers.

"Humph"! quoth one, "costumes by LaneBryant."

"Lane-Bryant nothing", growled the other. "Costumes by the American Tent and Awning Company."

Continued on page 104

Continued from page 39

Yet of all this decent resentment, not a syllable appeared in their subsequent accounts of the performance.

The above suggestion that Guitry's laughter, when heard at home, seems to have less of a leer in it should not be misread as an intimation that a literal translation of his plays would horrify the American playgoer and bring the New York police a-battering at the theater door. The shifting current of the public taste has run too rapidly to justify any such idea. It is true that the lumbering authorities were heaved into motion this season against Asch's God of Vengeance, a second-rate tragedy from the Yiddish in which an undercurrent flowed from Lesbos. But there are reasons to suspect that the real resentment against that play had its source in other scenes.

Some Shocking Examples

I WAS less shocked at certain of the passages in The God of Vengeance, which was at least elevated by one magnificent performance, than by less conspicuous events in the theater which passed unnoticed and in the face of which a Grand Jury would be helpless.

I was shocked, for instance, at the observance of the thirtieth birthday of the Empire Theater, the house where the fond Charles Frohman brought us Maude Adams each year and every Christmas, with Peter Pan, filled New York with the sound of sleighbells and the music of a thousand nurseries. I was shocked when those in charge of this celebration thought it appropriate that the entertainment should reach its climax in a display of Gilda Gray's talented torso attended by maidens from the Follies clad in the conventional fig leaf. One could not help wondering if the spirit of Charles Frohman visited his beloved playhouse that night and, if so, how long it lingered.

I was shocked when one of our younger actresses, atrociously directed, if at all, in a revival of King Lear achieved the incredible by making Cordelia seem insincere. Shocked, too, when the same revival distinguished itself by allowing the magnificent role of the Fool to be played by an ineligible girl. And shocked into a kind of insensibility when the Equity Players permitted their stage to be used for a morality play by Charles Rann Kennedy in which the role of the eleven-year-old Christ child was fearfully embodied by an exceptionally tall, undernourished young woman with commencement-stage gestures and bobbed hair. Yet they call out the police for The God of Vengeance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now