Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

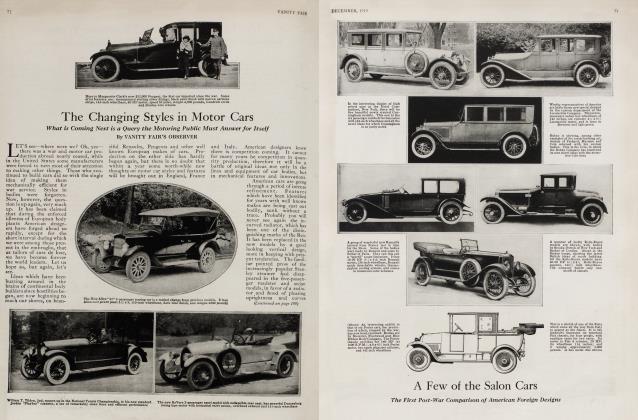

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Vanity Fair Car

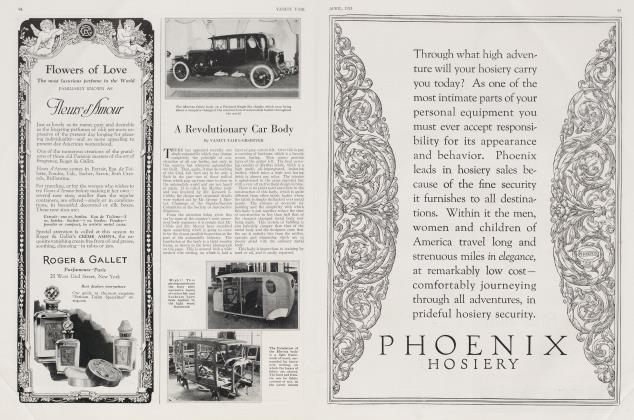

A Special Rolls-Royce Sedan Which Incorporates Many Features We Have Recommended

BY VANITY FAIR'S OBSERVER

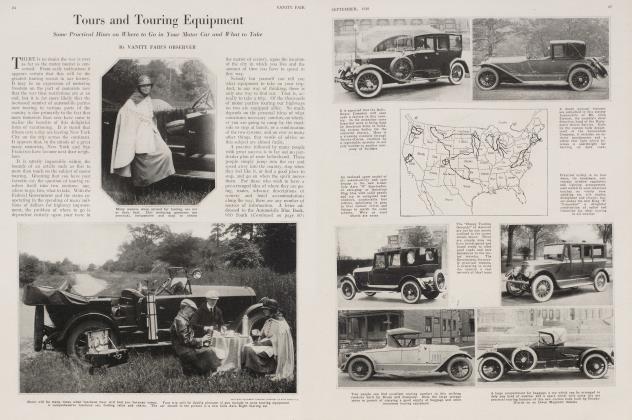

FOR those discriminating motorists who are interested in the finer points of motoring and the small but important signs of progress which elevate some motor cars above the level of the commonplace, a close study of the car described in this article will be well worth while. It is a Vanity Fair car, designed by a well known inventor after a long study of the standard and custom built automobiles of America and Europe and a close perusal of the articles which have appeared in these pages and in which we have recommended certain changes in cars as they exist today.

It is difficult to give this car a name. It is convertible in a few moments from one type to another. In one position it is a striking permanent top touring car. In another it is a cosy, family sedan. In still another position it becomes a more or less formal sedan-limousine, with the driver separated from the passengers by a glass partition. The design of the entire car and its multitude of interesting details is the handiwork of Mr. C. Fuller Stoddard, inventor of the Ampico reproducing piano and the pneumatic mail tubes now used by the New York Post Office. The body work was executed by Locke and Company on the newest American Rolls-Royce chassis. The result is a car of great usefulness, splendid riding qualities and a degree of convenience and comfort which this writer has never before seen embodied in an American machine.

In spite of the originality of some of its features, there is nothing freakish about this car. There are one or two distinguished coach builders who disagree with us on this point. We maintain, however, that this is 1923 and that some of the coach building traditions which have lingered since the early days of horse drawn vehicles simply must be set aside in favor of ideas which are more modem and more in keeping with the speed, power and grace of the up-to-date motor car. In the construction and fittings of this car, Mr. Stoddard has used excellent taste. There is not anvwhere a bizarre note, yet in its main features the machine is as different from the ordinary car as light is from darkness.

(Continued on page 98)

(Continued from page 80)

A clever arrangement of pillars and windows which slide up and down contribute the convertible features which enable the owner to have three separate types of car at his disposal at a moment's notice. The windows themselves are one of the most interesting features of this unusual car. They are low, being only 15 inches in height, yet their bottom line is at such a distance from the floor of the car that the vision they afford is practically perfect from every seat.

We have pointed out time and again in Vanity Fair that the seats of European cars are so built that you sink down into them with utmost comfort, whereas in a majority of American machines the seats are high and badly designed, so that the passengers are placed above the line of comfortable riding. In other words, as countless engineers have pointed out, one great trouble with American cars is that you ride on them rather than in them. This point has been very carefully thought out in Mr. Stoddard's car. A glance at two of the photographs will show that the seats are so deep as to supply perfect ease for the body and yet give the utmost of riding and driving comfort.

While the car was built ostensibly for four passengers, the seats are very wide, so that three persons of ordinary size may occupy them, both front and rear, with perfect comfort. Two small folding seats have been provided in the tonneau for extra guests, and there is a dividing arm rest in the rear seat which folds back into a recess in the upholstery.

When the glass division is drawn up from its nest in back of the front seat, and the car becomes a formal sedan-limousine, communication with the driver is rendered easy by a dictagraph type of automobile telephone. One of the most interesting features of this car is that, in any of its three positions, it bears in appearance no relation to the clumsy, awkward vehicle which usually goes under the name of "convertible".

VANITY FAIR has often protested at the enormous "blind spots" which even the most distinguished coach makers build into their most luxurious cars. There are practically no blind spots in Mr. Stoddard's machine. The slanting front is supported at the corners by two sturdy bronze triangles of his own design which, with the aid of a fifteen inch bronze extension which runs along the roofline toward the rear on each side, is amply strong to hold up the weight of the front part of the roof without impairing the driver's vision. This represents the accomplishment of an idea which might well he considered by most of our best custom body makers.

The windshield, unlike that in many American cars of all classes, is not divided in the middle. The division line is low and does not interfere with the driver's view of the road ahead. The car has a right hand drive, but it is easy to get out through the right hand door. Last week I inspected seven newr $10,000 sedans which have been delivered to the New York branch of a well known factory. They were the work of a famous designer, yet they had faults which even an ordinary motorist might he expected to pick out. One of these lay in the fact that when the door to the driving compartment was open on the driving side, the front seat extended so far forward that there was less than two inches clearance. This means that it is necessary in those cars for the chauffeur to lift his feet up over the front scat before he can sit down behind the wheel. No such piece of had designing exists in Mr. Stoddard's machine. The doors, especially the front doors, are so wide that they offer plenty of room for comfortable ingress and egress.

AT last year's Salon I took pains to sit in a number of the luxurious cars on display and, in many cases, "took pains" is a perfectly correct expression. I remember particularly one $15,000 sedan-limousine with a right hand drive. The door handle was in the normal place, and every time I attempted to turn the steering wheel my elbow struck the door handle, several timesforcing the door tocomeopen and every time doing more or less damage to my elbow. In that car the steering wheel was set so low that only a chauffeur with very thin legs could possibly get in under it. Mr. Stoddard has overcome both of these difficulties. His right hand front door has no handle in the ordinary sense, on the inside. Instead it has, well forward, a conveniently placed little knob which, with a minimum of effort, can he pushed forward, thus releasing the door catch. A very slight pressure of the elbow outward opens the door. His steering wheel is the epitome of comfort, yet there is plenty of room under it and in front of it to supply driving space and convenience for even the Cardiff Giant.

The traveling trunk at the rear is of Mr. Stoddard's design, and its construction cost him $700. It is of aluminum, heavily covered with leather, and contains three specially built suitcases.

The designer wished to carry his tools under the front seat, but he found very little room there for the purpose. This fact, however, did not present an insurmountable obstacle. He constructed, with his own hands, three tool boxes of light hut solid wood, with grooves cut to the exact size and shape of the various tools.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now