Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Plea for the Bucolic Life

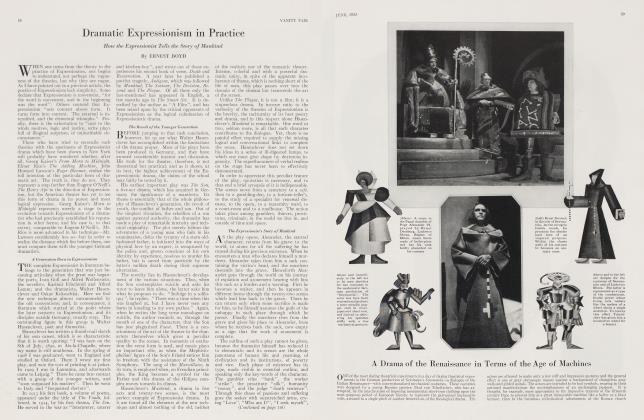

An Italian Philosopher Finds, in the Country, a Refuge from Democracy and War

ETTORE MARRONI

THE enjoyment of country life is often a discovery of advancing years, when we are past that state of dementia which is called youth. At the time when I myself was suffering from that mental malady, the country seemed to me the senseless home of raw quinces and of cherries hung inaccessibly on the tree. Now I am filled with pity for you dwellers in the city, who spend your days gazing into shop-windows at materials made of paper—since the war all materials are made of paper—and, in the evenings, when at the theater, feigning interest in those doings of others which are called comedies.

Here, in the country, I live among marvelous things! I am not speaking of the sky and the sea, whose ballets of clouds and waves remind the inconsistent of scenes of romance. I speak of the divine earth and her treasures; of certain silvery cabbages which gleam in the sun; of certain new leaves of plants which smile through their wrinkles like faces of new-born babes; of the chromatic harmonies, worthy of some old Chinese masterpiece, hovering over the gourds—red and yellow, or orange and green; of the lovely lupins cut from almost inpalpable velvet with the finest edge of white; I speak of the lizards who listen to my whistling with a pose of the head so charmingly distinguished that, in my time, among ladies of what was called good society, it was already rare.

What an artist is the Eternal Father! How rightly are we taught that His acts must not be judged. The great artists must be taken as they are—and such as this they are. . . .

AMONUMENTAL SOW lies sunk in the silver and crystal sand, with her eight sucklings, shell-colored, encircling the maternal croup. Another, tiny like the adventurer climbing up among the hundred gigantic divinities, each one two-headed and four-armed, in some Indian temple, scrambles rudely about the hill-range of teats hunting for a nipple. Upon this gray and pink allegory of beatitude in innocence beam sun, sea and motherhood. Apparently my sympathy penetrates the armor of lard which encases this honest happiness, for the little half-shut eye seems to blink upon my human conscience with an elusive smile of pity.

WHAT was it that old Marianna was telling about yesterday, as she noisily sipped her coffee?

. . . "Those eight creatures sleep in a dark hole on the fourth floor, Opposite the stairs, but the door does not shut. Their mother, tired of beatings, has run away; the father works all day in the factory and doesn't come home at night. I can't sleep for thinking of Rosinella, the eldest, who is already fourteen, and of that door that can't be shut." . . .

THIS year the vineyard was pruned by the wife of Salvatore, who, made foolish by malaria in the Albanian campaign, has become henceforth a useless mouth on the farm. The insoluble domestic problems weigh this poor women down, despite the fact that she works fourteen hours a day and steals more than could a whole family of monkeys. But Salvatore, feeling himself an "unknown soldier", puts a righteous pride in forgetting to manure the lettuces and in allowing the medlars to rot upon the branch. I had been very careful not to disturb the pride he has in his sacrifice by telling him that Italy had thought well to abandon this Albania whose conquest had been bought by the loss of his mind—(how many other fathers of families, most of them also from this countryside, paid the same hideous toll)—but suddenly this very morning he spoke to me of it with placidity:

"Signorino, the government has left Albania and there will be no more dull-witted soldiers like me." Obviously he felt himself distinguished and privileged.

The old servants in the house knew the grandfather of Salvatore; he also was an unknown soldier, a fighter in '66, but he escaped intact from the glory of arms. Every Sunday he would pin on his medal to go to mass, and, with certain repetitions of phrases, always the same (for repetitions, as you may see in Homer, give force to the epos bellico) he would relate how it was he had fought against the French.

"Against the Austrians, you mean." .

But, emphatically, the old man would asseverate: "No, against the French". No authority could ever make him change his opinion. His whole family, which had come in those days from Sicily, could attest it; the war of sixty-six had been fought against the French, those of the Vespro.

The socialists are wrong indeed when they accuse democracy, like a wicked step-mother, of excluding the proletariat from the benefits of education. I have spoken of the European war with many men of property, many professors, lawyers, students, deputies, senators—gentlemen all, or sons of gentlemen. They had every one of them felt the war in just Salvatore's way and thought about it with the exact wisdom of the old man. It seems to me that the motherland nurtures her children in a same civil consciousness, without any class distinctions whatever.

THE yard where the geese are kept, I find, affords edifying lessons of which I am much in need.

A hundred geese, two hundred, more than two hundred—but so united! All bend to the right when one bends to the right, and then all together to the left, and again to the right— and not through coercion, nor at a command, like slaves, but by the spontaneous synchronism of a free people. In this inspired discipline, the scattered herd attains sublimity, and brings to mind the picture of waves destroying quays and houses, stronger than the thought which had constructed them. With nothing, with a breath, rhythming a single qua qua ra, tirelessly cackled, behold how they create for themselves a conviction, a faith, a common soul. For now they are no longer a hundred, two hundred, over two hundred beasts, but a single beast, a people—one in beak, in feathers, in noise, in terror, in fury; a sonorous banner whose glorious waving of white and yellow puts to shame the motionless green silence of the meadow.

The lateral look, peremptory, capitoline, of the redeemed palmipeds in their collective intrepidity, a look of firm principles, of strong principles, thrusts upon me the lesson in democracy of which I stood in need. Suddenly I interrupt with the cry:

"Down with militarism! Long live democracy!"

"Qua qua ra! qua qua ra!" At the triumphal shout, the new-born sparrows shut their gaping beaks and crouch down hastily into the nest.

"Hurrah for poor President Wilson! Hurrah for the League of Nations!"

"Qua qua ra! qua qua ra! qua qua ra!" And the bees swarm and the ants scurry about, seemingly unashamed of their mute utilitarian communities deaf to the clamor of the ideal. As if distilling honey and building cities sufficed to make a nation! The breath of God is required, and how can there be breath without a voice? We want to hear your qua qua ra, O bees and ants!

This morning I caught myself sniffing greedily the stink of the stable-litter. Was this a symptom of degeneration? No, it happened that last night some impulse out of the blue led me to read again a chapter or two of Gabriele D'Annunzio's Piacere.

I HAVE learned to know, one by one, the trees of the orchard, and now we are great friends. As I pass under the branch, so bowed with its burden that it grazes my head, I lift it with careful gentleness as if I were replacing in the cradle the pendant arm of a sleeping babe. Can you remember without pleasure our wranglings of last spring, when we could not yet tell whether the trees were almonds, peaches or apricots; and, when we learned that these leafy masses, in which the setting sun entangles its rays, were quinces, what a touching gratitude we felt, as if we were to be fed with acorns?

How late we learned this easy science so full of joys! Always late, in this life, yet always at the right moment. And now, as the cool evening descends, flooding the earth with suave delight, let us listen together in silence for the heavy thud on the grass of the ripe peach as it falls from the bough.

As we return, let us bear to the right and so avoid passing near the old cherry tree that is to be cut down tomorrow because it no longer bears fruit. Against the death of a tree I revolt as I do against whatever takes cognizance only of brute economical reason or of this stupid physical life. That which does not really live, but merely vegetates beyond the confines of good and evil, why should it die? Take from the concept of death the principle of liberation and redemption, and nothing remains but the image of matter in putrefaction. The plant perishes, man alone dies. Only to the bearer of the world's sorrow and pain, only to man, belongs what the great Italian poet, Leopardi, exquisitely called "the pleasantness of death"!

WITH its contorted trunk, crooked tendrils, parched and fissured bark, the vine, writhing, unable to stand without support, seems an agitated, possessed being among these calm trees that only the wind can move. Through its fervent fibers, it draws intoxication from water and sunshine, to transmit it, distilled in wine, to those poor natures who cannot find intoxication for themselves. Abstemious drunkard, the vine is my sister. What happiness to see theel I must sing The vineyards, and salute the fig-trees grown,

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued from page 74)

Not even as a child did I feel any terror of death, but I shrink with horror from a cemetery. Again a community, a city, a country, a republic! Again my equal who is yet so unequal! Again the neighbor who is so far removed from me! To serve others, to die for others—yes, I can understand that, but why a common sepulchre? There was a time when I, too, would have with enthusiasm offered my life to my country, but I was living then in foreign lands. It is not the worms which give me a shudder; it is knowing that there, below, is the permanent seat of public opinion, synthesized from all the dead ideas buried with all those dead men.

Little peach-tree with pink cheeks, all branches and blossoms, whom in my heart I hear wailing with restless longing for fruit-bearing, thou shalt yet make honey of my acerbity, for it is at thy roots that I shall lie. And if such capricious burial be forbidden by the law, we shall bow to the majesty of the law, rendering unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, slipping into the hands of the magistrate of the democracy the justly adequate amount.

My First Forest

VINE and orchard, sinking afternoon sun, my life's maturity—the three notes sound in perfect harmony, but the key is minor.

In contrast I remember my tumultuous joy at the first sight of a forest. I was more deeply thrilled than by any other revelation of my youth. They could not keep me from getting lost; I fed myself on strawberries and water from the brook: I was Robinson Crusoe, Rinaldo whose horse had escaped, Siegfried in colloquy with the birds, everything which in spirit and in truth I was, I shall be or am—and always I was the only citizen, the whole state, and for that half day no longer an anarchist. On the contrary, I found it natural to shiver and be afraid—feeling among the dark branches' the dark humidity of night.

But after I was recaptured by the people from the inn—the adventure did not take place in the virgin forests of the Amazon, but in a piney ravine of the Apennines—lo! it was all a dream, as it has ever been, from Diogenes to Rousseau, when a man, disgusted by history, tries to return to nature—for what can nature be to him but history in conflict with itself? But what does that matter? This flight from the world creates other worlds, this day-dreaming shatters many things of solid foundations and we laugh today at the sight of the Maurras, the Daudets, followed by the usual Italian myrmidons of the French kitchen, endeavoring to drive out of life the great JeanJacques Rousseau. _ Since romanticism bequeathed to Liberty the forest, the glacier, the Alp, the abyss, darkly and vertiginously silent and tragic, only fools can think to find her still in the crowd or on the piazza. It is perhaps for this reason that I am so bad an Italian; Italy has very many piazzas, and hardly a forest left.

I heard yesterday some people who were returning from that part of the Tyrol which used to be called the Alto Adige praising the stupendous forests of the region, conserved by a forestry legislation which was the best in the world. So the larches and fir-trees of the Tyrol are still standing! I feel as if I had had news of a friend long-lost and mourned for dead.

The herds of cattle, despoilers of the Apennines, have given us at least curds of goats' milk, and sheep's cheese which stings and explodes in the mouth—whereas the rational thinning of forests in industrial countries produces only paper for newspapers. They destroy the trees, those living marvels, the joy of the earth, that the misery and spiritual servitude of the multitude may be fed upon commonplaces: a function for which at one time sufficed a few thousand preaching friars scattered over Europe; now we employ for the purpose parasites by the hundred thousand. Buddha, Jesus, Socrates, never wrote a single line, and were satisfied with a dozen hearers. Readers by the millions crowd around the crime— booth of the Northcliffes, those dealers in stupidity and iniquity. A German pessimist well said that the calamities of his people were an expiation of the guilt of having invented the printing-press.

Aristophanes on Peace ALL you who are sick of war and long for peace—I tell you, you do not know yourselves. Peace means to you a greater income, a higher salary, a more exalted circle, more vanity, more popularity, more luxury, in fine, more effort. You are men of the city. All our contemporaries are city people.

Dispenser of the Gods' sun-mellowed clusters,

With what words shall we greet thee? A>id from where

Procure ten thousand amphorae to give thee A filling welcome? Empty is the cellar. Pomona, we salute thee! And thee, Galloria!

How sweet thy face, how ravishing the fragrance

Of calm and myrrh which steals into my heart.

And this,

Of fruit-hung trees, together with the sound Of Bacchic feast, of comedies, of songs By Sophocles, of singing flute and thrush. . . Of ivy, of the olive-press, of tiny Soft-bleating lambs, of the breasts of girls Scampering through the fields, of fantasies Wine-given, urns o'er-turned,

And of so many other lovely things.

Such an enchantment of laughing images, fluttering to salute Peace, which in truth is singing in their hearts! But it is a poem by Aristophanes: that is, two thousand three hundred and forty-one years old. The men who, though dehumanized by ten years of war, publicly applauded in the theater this passionate sighing after the sweetness of life were, they too, votaries of the furies of democracy, that regimen founded upon the public passions and therefore devastator of the State. Then, too, did peace shine forth, a gleam between two ruins, ephemeral as the lovely sound of the verses which announced it, and the thirty years of war were the suicide of Hellas, as the last war was the suicide of Europe.

But yet, though citizens within the walls, those believers in democracy were at the same time landed proprietors or small cultivators in the country. Full of rustic tastes, satiated with quiet, with calm, with oblivion, they came and went in the tiny metropolis (Athens numbered, at the time of Pericles, twenty thousand citizens) surrounded by fields and vineyards; while our country-side is shrill with trains, invaded by newspapers, abandoned by the emigrants—shaken by the roar of the immense cities which spread over it the shadow of their arid mass.

O People, hear! The country-men are seizing Again their tools and to the farm return Leaving their javelins, their spears, and swords.

The land is filled with immemorial peace. The laborer's paean lifts our hearts anew. Day dear to all good folk and ploughmen, hail!

(Continued on page 120)

(Continued from page 116)

Planted in youth, and for so long unseen. Good people, thank the Diva, who has freed us

From dark Chimera's fear, and from the Gorgon.

Then let us hasten home to farm or vineyard

Carrying provisions with us soaked in brine.

Yea, I do long myself, the fighting over,

To labor in the fields, and to turn over With hoe and pitchfork, my beloved land.

Behold, oh my readers, how shallow is your longing for peace confronted by that which animates these men, who care not to ask how the war is ended if it but end, if only they may return to the farm, to the complexity of physical burdens and joys, of spiritual rest, which it represents. Cleon, Lammarchus, Nicias, the leaders of both parties are all alike to them, and they ask only never to hear of them again. Is there, among my readers, a single one deliberately ready to hear nothing more, literally nothing, end as they may, of the international debates, of the revision of the treaties, of Russia or of France, of Foch or of Lenin? If there be one, I offer him these delicious verses:

Think of all the thousand pleasures, Comrades, which to Peace we owe,

All the life of ease and comfort Which she gave us long ago:

Figs and olives, wine and myrtles,

Luscious fruits preserved and dried,

Banks of f ragrant violets, blowing By the crystal fountain's side;

Scenes for which our hearts are yearning, Joys that we have missed so long . . .

—Comrades, here is Peace returning,

Greet her back with dance and song!

Welcome, welcome, beloved! How we rejoice at thy coming.

I was destroyed with thy longing, hot with desire

To return to my fields.

Thou weri always, Eirene, yea always, of all our possessions

Most precious. Thou takest delight in our pastoral life.

In thy reign we enjoyed the delectable gifts that thou bringest

Many and dear and so sweet! To the tillers of earth

Serenity art thou, and bread.

Now will all the tiny shoots,

Sunny vine ami fig-tree sweet,

All the happy flowers and fruits, Laugh for joy thy steps to greet.

The world war will probably prove to be to the national democracies of Europe what the Peloponnesian war was to the citizen democracies of Greece: the end of autonomous power, the absorbtion into the superior Macedonian hegemony represented today by the Anglo-Saxons, who are masters of the seas, the continents and of raw materials. But, in the analogy of the historical situation, what a psychological difference! The Athenians of Aristophanes found refuge like children in the realms of fantasy: they disconnected life, converting it into laughter, games, dreams. Compare the joyfulness and the idyllic frame of mind of Aristophanes with our spasmodic tension in 1915 and in 1920. Yet then, too, the fate of cities and citizens was at stake: they were threatened with the burning of houses and temples—more than this, with slavery of their very persons. And still they laughed. They laughed and dreamed. The dominant note was the longing for solitude in the country and for its informing peace of the senses, precursor of the peace of the spirit; whereas we, who would look upon this quietness as the death of the spirit, and abhor it, cannot possibly bring ourselves to envisage a complete detachment from public events. Would you be willing to plunge into the universe of the barnyard and the fields, and never again to see a newspaper?

If so, then in truth you do want peace, and Aristophanes in his marvelous comedy Peace will lead you to that spot (in Arcady?) where Hermes showed Trygceus the cave in which Peace had been entombed, so that you, too, may free her and enjoy her. But mark this: if even once, on your way, you turn to learn whether Marshal Foch is invading the Ruhr or if a new revolution has broken out in Mexico, that instant's faltering will suffice to keep you forever from entering the sacred shrine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now