Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Comic Spirit in Modern Art

JEAN COCTEAU

A Note on the Profound Realism of Exaggeration and Caricature

FROM the sea-side, where I have come for a rest Igor Stravinsky's last adventure presents itself with a simplicity and relief which makes it easily comprehensible at once.

The critics and the Parisian public, having grown accustomed to VOiseau de Feu, received Petruchka very badly when it first appeared; then, when they had got accustomed to Petruchka, they hissed Le Sacre du Printemps. To-day, accustomed to Le Sacre, they are sulky about Mavra.

Stravinsky has indeed, a well planted mind. I mean by that, well planted as well brushed hair is well planted—with just the right amount of hair on each side of the part. There is no disorder in this Slavic genius. He sounds his organs, takes care of his muscles and never loses his head. He knows that an artist who spends his whole life in the same costume ceases to interest us. Consequently he transforms himself, changes his skin and emerges new in the sun, unrecognizable by those who judge a work of art by its outside.

After L'Oiseau de Feu, in which one felt the influences of Rimsky and Wagner, came the mysterious, picturesque, highly coloured, profoundly disturbing Petruchka. After Petruchka came Le Sacre du Printemps, which shot up in the orchestra before our very eyes like a tree in one of those moving picture films that shows plants growing at such a terrific rate. Le Sacre is harsh, sad, stark, stubborn, like the beginning of the ages. But just as Bayreuth established a sort of extra-musical religious atmosphere, which brought to earth the reign of the paste-board sublime, just so does Le Sacre by its grandeur and its power bring a sort of simplicity among the initiated—quite different from the other, to be sure, but also dangerous for young musicians. However, a work like Le Sacre, a really monster work, is always dangerous. Dangerous for others and dangerous for the author. A disorderly genius, with a badly planted intelligence, happening to give birth to such a work, would be likely to stop there, to make capital of it his whole life, as if it were a gold mine.

See how Stravinsky escapes from this situation. I have not heard Mavra but I get a very good idea of it from reading the unfavorable criticisms. A composition by Stravinsky never gives the critics what they expect of it. What do they expect? A work which resembles the one before it or perhaps something so vague, so mediocre, that a great man would never be able to produce it. On this occasion, the Noces would perhaps have cajoled them, for the Noces, which precedes Mavra and Renard (another misunderstood and perfect work) is descended in a straight line from Petruchka and Le Sacre. But choral difficulties have transposed the chronological order of productions, and we shall hear the Noces later.

Our brave post-impressionists, who have already been disturbed by Le Sacre in the midst of their sonorous little musicale, on this occasion virtuously refused to allow themselves to be led into a resort of ill-fame, that is to say, into our camp. Think of it! Stravinsky bringing the homage of his supreme contribution to the endeavors of Satie and our young musicians. Stravinsky the traitor. Stravinsky the deserter. It would never occur to any of them to think: Stravinsky the Fountain of Jouvence. For no one ever gives the masters credit. It would be simple to say to one's self, "He is stronger than I. His instinct is surer.

He must be right. It would be wise to follow him!" No. Everybody thinks, "he is mistaken and I—clever fellow—am the only person who knows it." This downpour of drivel, of lava and ashes, is, however, a good thing for a work. Thus the critics think to destroy it but they only cover it up, they protect it and preserve it, and a long time afterwards an excavation brings the marble to light, intact.

Overleaping the Fashion

THIS is precisely what has happened to me with my last book of poems: Vocabulaire. With each of my books I move, I change my skin. In this case, I wanted to express myself with a strict avoidance of "modernism" and all its grimaces, which the naifs take for novelty. Now that our younger generation is walking in the foot-prints of writers who have been misunderstood and rejected in their period (Rimbaud, Lautreamont, Mallarme), it is only natural that novelty should be misunderstood and rejected by young men who believe that they are making innovations when they are only conserving old anarchies.

In Vocabulaire, I have tried to avoid the fancy and the obscure. I simply draw. That is what the younger generation and the critics do not understand. They can see nothing but a retreat in this boldness which overleaps the fashion.

So I come to the title of this article: The Comic Spirit in Modern Art.

Here again a grave misunderstanding presents itself. There is comedy and comedy. Premeditated comedy and involuntary comedy. In a Chinese play the heroine becomes jealous and her terrible scene with her husband makes her so sick that she vomits. Be sure that the Chinese public does not find this scene funny but weeps over it. If it were played in France, it would disgust people or make them laugh. So it happens that certain abbreviations, certain poetic brutalities, certain powerful reliefs, excite laughter in an audience which is accustomed to the banalities of the contemporary theatre. The laziness of the public has gradually become so great that in order not to shock it, it has become customary to put on the stage real arm chairs, real doors, real costumes and real sentiments without changing their shapes or magnifying them at all, in the interest of the special optical requirement which makes it necessary for the actors to put on make up and raise their voices. So imagine the wild laughter which greets any attempt to treat synthetically a setting or a dialogue.

Now just at present the poetic theatre, far from being poetry of the theatre is simply poetry in the theatre—which amounts to attempting to show a very delicate lace from a great distance and demanding that the eye should perceive its finest threads. In Les Mariés de la Tour Eiffel I wanted to produce poetry of the theatre. That is to say: to image the action and to remove images from the text; to accompany this action— more real than the real (and in this sense unreal)—with the simplest words and with the commonplaces which everybody has in his ears, as everybody has ordinary objects or the Venus de Milo in his eyes.

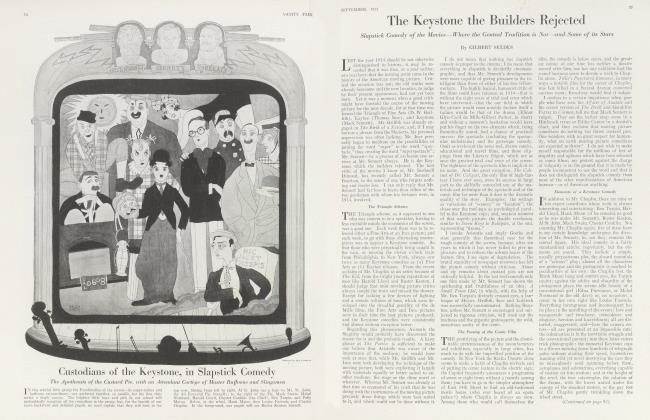

In Vanity Fair, Mr. Edmund Wilson, Jr., in the course of an extremely kind article on my dramatic works described them as being akin in spirit to Anglo-Saxon nonsense. It seems to me that he is mistaken, unless it is nonsense which imbues our smallest acts, the life of every day. The idea of nonsense occurs to him because he finds in my compositions, in which dialogue, choreography, music and settings all work together, an atmosphere of the absurd which is really produced by magnifying reality, by putting it on stilts. This realism—inordinate, selective, disorganized and reorganized, as it is—is for me the only one which counts. It is the realism of Shakespeare, of Moliere. Shall I dare to add that it is the realism of the great, of the tender Charlie Chaplin. (I hope that this phrase may reach him and bring him the homage of our whole generation.)

Taming the Public

FURTHERMORE, I admit that in order that certain innovations may see the light at all, may neither terrify nor ruin the producer, they should be presented in a form which deceives the public, which tames it and makes it absorb the comforting drug, as it were, without knowing it. At the very moment when I am risking my most difficult feat, I am careful to amuse it, to throw it sugar. The same amount of relief which the public is willing to bear in buffoonery (that is, when buffoonery is used as a pretext) they would reject in serious drama. Since there would be no reason for them to laugh, their laughter would disturb the performance, would fatally interfere with it. In Les Maries even more than in Le Boeuf sur le Toit or in Parade, I am -working under cover of this laughter. In the same way, Charlie Chaplin, protected by his comic falls and accepted for their sake by our great public, is able to arouse in a few of his spectators an emotion comparable to that which one gets from Heinrich Heine.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 66)

It will take years and years and many victims to duty before it will be possible to vanquish the contemporary banalities —among others, the theatre of the boulevard, that veritable old photograph album, whose pages the yawning public turn over backward and forward and of which, none the less, it is beginning to tire without being aware of it. For our efforts are not blows in the void. Already there is a theatre taking shape— born of the music hall, the cinema, the circus, and the ballet—which, without filling up for the public the void that they feel about them, does not fail to make them conscious of it by rendering even more insipid than before the taste of the partem et circenses which fifth rate bakers and crapulous producers cook for them and offer them.

The False Humour of the New

PEOPLE are deceived by this false humour also when they come for the first time to our poetry or our music. In 1900 Pélléas was comic. Open the dictionary and you will see that Rimbaud is a "fantaisiste". Baudelaire answers this reproach of "fantaisie" very well by saying that all poetry is "poesie fantaisiste" because "fantaisie" is precisely each poet's peculiar way of feeling and seeing things. Every audacity in the arts (and every period has its own— contrary to the opinion of the naïfs who are vastly impressed by our "modernism"—an absolutely meaningless word), every audacity in the arts establishes between itself and the habitual manner of feeling of the time a displacement of equilibrium which excites laughter, exactly as a lady who falls down as she is getting off a street car excites laughter. Now a fall of this kind is not funny in itself. A new combination of rhythms and notes by a musician is for the audience only discord and charivari awakening the old laughter of college days. This false humour makes the critic conclude that the work in question is a humourous work which is a great failure as a piece of humour. "That's not funny," they say. Of course it isn't funny. Because even if it is a question of humour, the humour is only a colour which is spread upon volume. The volume has no part in it. Thus I see Oedipus, Iphigenia or Macbeth in the relief, the volume of certain scenes in Les Maries—where the public can see only nonsense and broad humour.

Why deceive the public? you ask me perhaps. For the sake of politeness and in order to be left in peace. They are amused, they pay for their seats and they applaud—that's the principle thing. It makes it possible for me to work as I please, and, I repeat, to tame them at the same time for more overt feats of audacity. Nothing is more difficult than to make certain people understand that there exists a world between caricature and, for example, the style of a Derain. All the strokes by which this painter asserts himself, corrects the objects he paints in his own image and makes the human face obey his own rhythm, seem caricatural to the public, who have long been accustomed to see figures, objects and landscapes either in the light of mediocre works of art or in the light of fine works of art in which they are impressed only by the mediocre aspect involved in every production.

The painter is a critic of nature. Now the criticism of M. X neither interests nor instructs us. Why should we listen to M. X? The only criticism which has any value is that which is made by an artist whom we love, because it constitutes another means of bringing him into relief to our eyes. The work which is criticized becomes nothing more than a pretext. It is the same as in the case of one of Derain's models. It is not the bottle, the napkin, the Italian lady, the tree which interests us, but the way in which Derain judges them and corrects them. Let us consider them as a foundation, a point of departure, a springboard, which concern us no more than an audience is concerned with what goes on behind the scenes—and so let us forget them. Then, as soon as the picture stands alone, well detached from the ties which bound it to that which first gave rise to it, the rupture between nature and art no longer exists and the desire to laugh ceases.

I have seen people laughing less before the cubist canvasses of Picasso than before the paintings of Derain. In fact the work of Picasso, with all ties apparently cut between its model and itself, reached an altitude which prevented the eye from establishing any connection. The public did not laugh any more than in the presence of a carpet or a stained glass window. And yet what a difference between decorative work and work like this, whose persuasive force comes precisely from the fact that it extends a thousand deep roots down into reality, that it deceives the eye like those optical illusions which produce such striking effects of perspective.

If you should tell the spectator that this combination of strokes and lines represented a piece of still life or a seated woman, you would immediately produce the rupture, the fall and the laughter.

This subject deserves a long study enriched with details and examples. Alas, I must confine myself here to the bare outline permitted by the limits of this article.

For the article or the study alike the conclusion would be the same. In Le Coq et l'Arlequin I wrote: "the laughter of the crowd does not prove that a given work is a masterpiece but a masterpiece always excites the laughter of the crowd." The crowd laughs because it sees art perched suddenly on an altitude which we others see it reach little by little. It is the mechanism of laughter that Bergson describes. The critics are annoyed because their habits are disturbed and the artists because the rulrs have been changed in the game which they know so well how to play . . . and how to cheat in.

This tendency on the part of the public and the critic to see humour where there is none makes them tolerate more indulgently the unaccustomed methods of the new style. In fact, since they are looking only for farce and a way of amusing themselves, they find them in greater abundance among writers or musicians who take only the tics of a new physiognomy and transform its expression into a grimace. Even a fine intelligence like Mr. Mathew Josephson is deceived in this way, and takes the monkey who cuts his own throat for the barber.

Let no one suppose from this article that I am contemptuous of farce. Farce is an excellent genre. In it characters drawn in profile are clearly and sharply presented. But one must not confuse that which is intended to provoke laughter with that which provokes laughter by mistake.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now