Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEnglish Dialect and American Ears

Pointing Out the Apparent Inability of the Average Man to See or Hear Accurately

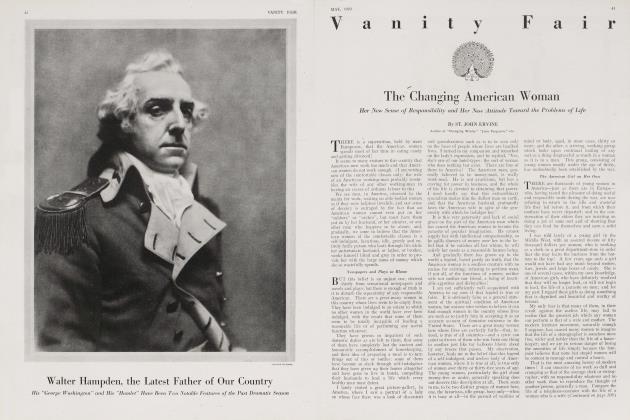

ST. JOHN ERVINE

WHEN I was in Chicago two years ago, I read in one of the newspapers of that city an account of a jewel theft which reflected very gravely on the efficiency of the reporter who wrote it. A young Englishman, belonging to the aristocracy, had married an American girl, and while they were on their honeymoon, thieves stole some of her jewels. A reporter hurried from Chicago to get a "story" out of the affair. He interviewed the young husband, who was reported to have said something like this: "Haw, haw, yaas, by Jove! Isn't it awf'lly jolly rotten, what? They stole the bally jewels, haw, haw! ..." I cannot remember the exact words put into this young man's mouth by the reporter, but they were not less foolish than those I have set out. If I had been editor of the newspaper in which the report appeared, I should have sacked that reporter without pity. He was a boob of the most booby character: a prominent member of what Mr. H. L. Mencken calls the boobosie. Only a complete idiot could have reported such an incredible speech! Only an ignorant or a malicious editor could have believed that such a speech could have been uttered by any intelligent human being!

The reporter had either decided before the interview that all Englishmen of aristocratic birth speak like congenital idiots, and therefore could not listen accurately to what was being said to him, or he was too lazy or incompetent to do his work properly, and trusted to conventional caricature to cover up his own deficiencies. Whatever was the cause of this childish report, he ought to have been sacked from his job. He was unfit to be a reporter. He might have earned an honest living as a hawker or in some other occupation which makes no demand upon the intelligence.

"Full Up and Fed Up"

THIS incident was recalled to my memory recently while reading an interesting sociological book, entitled Full Up and Fed Up, by Mr. Whiting Williams. Mr. Williams is a young and earnest and, I may add, good-looking, American who has a passion for enquiring into the discontents of working-men. He came to England in June, 1920, and returned to America in September of the same year. In the space of three months, he lived as a workman in various parts of England, Wales and Scotland. He worked with coal-miners in South Wales and with steel-smelters in Yorkshire. He worked as a casual labourer at the docks in London. He tried to get work in Glasgow. He lived in doss-houses and cheap hotels and in the homes of working-people and was almost devoured by flees in some of the dirtier doss-houses. His book is remarkably interestng, but not profoundly so, for Mr. Williams could hardly hope to give more than a superficial impression of working-class life in England after so brief and varied an experience of it. Moreover, Mr. Williams is tempermentally disabled from offering trustworthy judgments on sociological problems because he has a picturesque habit of expecting the worst to happen. It is, for example, quite clear that in July, 1920, Mr. Williams was convinced of the imminence of a revolution in England. He went about listening to disgruntled colliers in the Rhondda Valley and could hardly contain his excitement at the thought that he might be present at the beginning of the revolution. He almost saw King George's head struck off!. . . And all because of hot words from Welsh miners, culminating in an abortive strike. Mr. Williams hardly makes sufficient allowance in his book for the fact that the people in Great Britain say a great deal more than they do in the way of subversion. Heaven knows, industrial conditions in this isla-nd are bad enough to justify the gravest disorder, but revolution is a business into which Englishmen only go under extreme provocation. They are never nearer to it than when they say least about it. In any event, the revolution which so excited Mr. Williams' hopes has not yet come off and seems to have been overlooked.

What interests me about Full Up and Fed Up and recalls the Chicago reporter to my memory is the fact that Mr. Williams reproduces the conversations he had with workmen in England and Scotland and Wales in dialect. He gets much closer to the common speech than the Chicago reporter did to the aristocratic, but even so, he remains a long way from faithful reporting, and I cannot help thinking that he, too, has brought to the business of reporting a made-up mind rather than an acute ear. I imagine that most Americans form their impressions about English dialect from reading Dickens and do not check these impressions with the facts of contemporary life.

The Common Speech

THEY persistently overlook the great changes in social conditions in England since the days when The Pickwick Papers were written, and they come to England in the unshakeable belief that the less educated inhabitants of the country still use the speech of Sam Weller. They forget that we have had more than fifty years of compulsory education in England since Dickens wrote. They forget that the tendency to crowd into towns has completely altered the social groupings since he died. Dickens' novels are not untrue in spirit because they are no longer true in certain details. It is the indolent visitor, who will not take the trouble to check fiction with fact, who is at fault in this respect. Mr. Williams reports an English workman as speaking in these terms:

"If Hi wuz you, Hi'd walk right in ter the fountain-'ead o' these steel works 'ere, and sye, 'Hi wants ter see the manager!'—just like thot. With wot ye've done in Hamerica, ye'll get on fine 'ere."

And a soldier -whom he meets in the train is made to talk in the following fashion:

"Hi never seen a ranker make a good hofficer yet—awnd Hi've 'ad 'em over me a lot— hadjutants and all. In the hexercises and heverywhere it's alius 'Hi've been there meself, boys, and it cawn't be done. Hi'm too wise, boys.' You know 'ow it is. No, sir, never one."

Now, with all respect to Mr. Williams and his admirable book, I declare that never in his life did he hear any Englishman, illiterate or otherwise, talk in that fashion, unless, perhaps, it was a music-hall comedian trying (and failing) to be funny. I have lived in England for twenty-one years and I know the country, north and south, east and west, country and town, far better than Mr. Williams can ever hope to know it. I have lived among workingpeople in London, in provincial towns and in villages, and I have never heard any Englishman speak in that style. I have been in the army, as a private soldier and as an officer, and I tell Mr. Williams that if he imagines he heard a soldier saying "hexercises and heverywhere," then he simply has not got the faculty of hearing. The dropped h is common, but the sounding of it where it ought not to be sounded has almost ceased. I have never heard it sounded in a city, and only on one occasion have I heard it sounded in the country, where an old-fashioned fisherman, with whom I used to go sailing, would sometimes say "haccident" when he meant "accident." This man's younger brother never misplaced the hat all in this way, though he often elided it where it ought to have been sounded. The h is more likely to be dropped than sounded because of the natural laziness of most people over language. As many errors of pronunciation are due to slovenliness and indolence as are due to illiteracy, and it is far easier to omit the h from a word than to sound it. A considerable effort is necessary in order to sound the h in words where there is no such letter, and this fact, apart altogether from the results of compulsory education, makes it unlikely that Mr. Williams heard anyone in England saying "Hi" for "I" and "Hamerica" for "America." Let those who doubt this statement read aloud this sentence from the first of the quotations I have made from Mr. Williams' book:

(Continued on page 100)

(Continued from page 53)

"With wot ye've done in Hamerica, ye'll get on fine 'ere" and then say whether or not my argument seems sound.

The Scotchman as Cockney

MR. Williams' inability to listen accurately is made plain in the chapters on Glasgow in which he makes Scotsmen drop their h's. No Scotsman, born and reared and educated in Scotland, ever dropped an h in his life. The habit of dropping the h is a purely English one. No Irishman or Scotsman shares it in any degree. I have read stories by American authors in which Irishmen figure—Irishmen living in Ireland, mark you, not Irishmen born or reared in Bermondsey or Liverpool —and are made to drop their h's whenever they open their mouths! Mr. Williams not only makes Scotsmen drop their h's, but actually makes them use the Cockney accent. He makes a Glasgow woman say "chawnce" for "chance," and "byby" for "baby," and "sye" for "say," and drop her h's profusely ! He puts this Cockney pronunciation into the mouth of every working-man and woman he encounters throughout the country, whether in Wales, in the north of England or in Scotland, and I have no doubt that if he had gone to Ireland, he would have made the people of Cork and Dublin and Belfast use it, too. No one in England pronounces "baby" as "byby" or "say" as "sye" outside London and the county of Essex. A Scotswoman would probably say "babby" or "babeby" or "wee chile" or "wean" when speaking of her infant, but would never, never say "byby." Mr. Williams evidently got confused with the variety of dialects he heard during his three months' stay in England, and the result of his confusion is a bastard dialect, composed of bits of all of them, but untrue to any one of them. Take, for instance, the word "pound." Mr. Williams invariably makes all his working people pronounce it "poon' " which is how a Scotsman pronounces it. The costermonger in Whitechapel, the smelter in Swansea, the labourer in Middlesbrough, the collier in Barnsley, all of these people, according to Mr. Williams, pronounce the word "pound" exactly as the Scotsman pronounces it! But that is not the fact, anymore than the pronunciation of a manin New Orleans exactly resembles the pronunciation of a man in Boston. The Scots say "poon' " or "poond," the Northern English say "pun'," the Midland and Southern English say "poun' " and the Cockney says "pahn' " or "pahnd."

All of us are inclined to make Mr. Williams' mistake. His attempt to reproduce the dialects of England and Scotland are not any more ludicrous than the attefnpts made by some English writers to reproduce the dialects of America. A popular novel will fix a dialect in the careless mind, and people will continue to believe that men and women speak in that particular fashion long after they have ceased to do so. UntilI went to America, I believed that all negroes spoke like the characters in Uncle Tom's Cabin. Mr. John Drinkwater clearly thought so, too, when he wrote Abraham Lincoln. I expected to hear a negro saying something like "Yaas, massa, dat am so!" when he meant, "Yes, sir, that is so!" I daresay there are many negroes in America who do speak in that way, in fact, Mr. T. S. Stribling's notable story, Birthright, makes this plain. But all negroes do not do so, and perhaps the most correct English I heard during my short visit to the United States two years ago came from the mouth of a red-cap in Boston!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now