Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

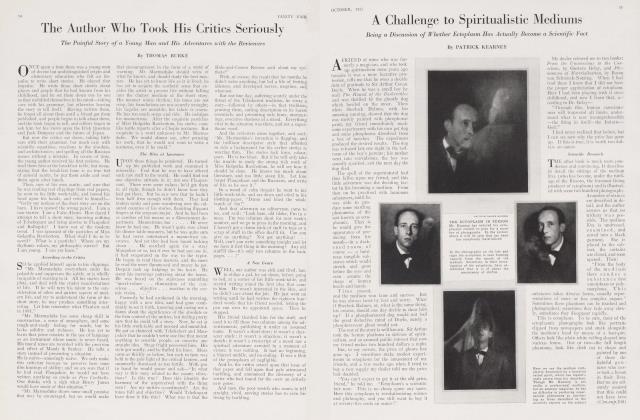

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Author Who Took His Critics Seriously

The Painful Story of a Young Man and His Adventures with the Reviewers

THOMAS BURKE

ONCE upon a time there was a young man of decent but undistinguished origin and elementary education who felt an impulse to write short stories. He obeyed that impulse. He wrote those short stories about places and people that he had known from his childhood, and he set them down one by one as they unfolded themselves in his mind—taking care with his grammar, but otherwise leaving the story to tell itself. Having written them, he forgot all about them until a friend got them published, and people began to talk about them, and the book began to sell, and editors began to ask him for his views upon the Irish Question and Jack Dempsey and the future of Japan.

But now the critics sat down, taking little care with their grammar, but much care with scientific equations, reactions to the absolute, and architectonics; and spelling all the Russian names without a mistake. In course of time, the young author received his first reviews. He read them first at the breakfast table, but recognizing that the breakfast hour is no true test of general sanity, he put them aside and read them again after lunch.

Then, sure of his own sanity, and sure that he was reading real clippings from real papers, he went to his little work-table, and bowed his head upon his hands, and cried to himself— "Verily my notions of the short story are on the bum. I have opened the wrong parcel. I am a non-starter. I am a False Alarm. How dared I attempt to tell a short story, knowing nothing of Tchekopant and being unwise to Flaupokov and Rollogski? I knew not of the modern trend. I was ignorant of the pastiches of Miss Golgotha Rawbottom. What shall I do to be saved? What is a pastiche? Where are my rhythmic values, my philosophic curves? But I am young. I can yet learn."

According to the Critics

SO he applied himself again to his clippings. "Mr. Marmaduke everywhere emits the palpable and suppresses the subtle, or is wholly incapable of reacting to it. All his stories have plots, and deal with the cruder manifestations of life. If he will turn his talent to the consideration of other and quieter aspects of modern life, and try to understand the form of the short story, he may produce something interesting. Let him remember what Flaubert said in 1881."

"Mr. Marmaduke has some cheap skill in construction, a sense of atmosphere, and some rough-and-ready feeling for words, but he lacks solidity and richness. He has yet to learn that prose consists in the use of language as an instrument whose music is never heard. His moral tones are recorded with the precision and effect of Moody & Sankey. He tells a story instead of presenting a situation. He is naive—amusingly naive. We only make this criticism because we perceive here some dim hintings of ability; and we are sure that if he had read Flaupokov, he would not have written anything so crude as Five Cocktails. One thinks with a sigh what Henry James would have made of that situation."

"Mr. Marmaduke shows some small promise that may be encouraged, but we would make that encouragement in the form of a word of warning. Mr. Marmaduke should write of what he knows, and should study the best masters. He has yet to know life as it is lived; he has yet to acquire the aesthetic sense that enables the artist to present life without falling into the clumsy medium of the short story. His manner wants rhythm; his tones are not crisp; his foundations are not securely wrought; his facades are unstable; his fabric is coarse. He has too much surge and tide. He indulges his mannerisms. After the exquisite pastiches of Miss Golgotha Rawbottom, his stories come like battle reports after a Chopin nocturne. But exquisite is a word unknown to Mr. Marmaduke. We would almost say, after perusing his work, that he would not want to write a nocturne, even if he could."

The Bliss of Ignorance

UPON these things he pondered. He turned up his published work and examined it miserably. Fool that he was to have offered such raw stuff to the world. He could find not one objective attitude in it; not one Flaupassant. There were some values; he'd got them in all right, though he didn't know how they had got there. But he saw now that he hadn't been half firm enough with them. They had broken ranks and gone wandering over the coloured counties of his stories, flaunting flippant fingers at the sergeant-major. And he had been as careless of his means as a Government department. Mannerisms, too....He never knew he had one. He wasn't quite sure about his dinner table manners, but he was quite sure he had never entertained a mannerism unawares. And yet they had been found lurking about . . . He searched again for a stray Maupokov or so, but if ever he had put one in, it had evaporated on the way to the typist. He began to read these masters, and the more he read the more flummoxed and muzzy he got. Despair took up lodgings in his heart. He spent his mornings pottering about the house. He was heard on the staircases mumbling "mood-values . . . elimination of the conscious . . . objective . . . reaction to the cosmic vision. . . ."

Formerly he had awakened in the morning, happy with a new idea, and had gone confidently to set it forth, knowing and caring not a damn about the significance of the absolute or the firm control of the unities, but feeling pretty sure that he could tell a story. Now, he sat at his little work-table and mooned and mumbled. He got so cluttered with Tchekebert and Maupakov that he couldn't write one line that meant anything to sensible people, or conceive one straight idea. Stage fright possessed him. His style got woolly, and he fluffed his lines. Ideas came as thickly as before, but each in turn was held to the pale light of the critical lantern, and summarily dismissed as too fertile. With pen in hand he would pause and ask—"In what way is this story related to the cosmic vibrations? Is this true? Does this identify the harmony of the unperceived with the thing seen? Are my unities co-ordinated? Are the tones full and objective? Would Tchekopant have done it like this? What was it that the Hole-and-Corner Review said about my epithets?"

With, of course, the result that for months he didn't write anything, but led a life of fretting idleness, and developed nerves, megrims, and what-not.

But one fine day, suffering acutely under the threat of the Tchekovert tradition, he wrote a story—followed by others—in that tradition, pruning them, cutting description-to its barest essentials, and presenting only hints, murmurings, evocative shadows of a mood. Everything vital to the situation was there, and not a superfluous word.

And the reviewers arose together, and said: "Mr. Marmaduke's invention is flagging, and the brilliant descriptive style that afforded so rich a background for his earlier stories is wearing thin. The stories lack force, colour, pace. He is too blase. But if he will only take the trouble to study the strong rich work of Miss Golgotha Rawbottom, he will see how it should be done. He knows too much about literature, and too little about life. Let him forget Flaupokant and the Russians, and write of life as he sees it."

In a mood of calm despair he went to his little work-table, and sat down and cried to his blotting-paper, "Damn and blast the whole bunch of 'em!"

And that afternoon an editor-man came to tea, and said: "Look here, old bloke, I'm in a mess. I'm two columns short for next week's number, and we go to press in the morning, and I haven't got a damn stick of stuff in type or a scrap of stuff in the office that'll fit. Can you give us anything? Not got anything? . . . Well, can't you write something tonight and let me have it first thing in the morning? Any old stuff'll do—it's only two columns in the back pages. . . ."

A New Genre

WELL, our author was sick and tired, but, to oblige a pal, he sat down, before going to bed, at a corner of his little work-table, and started writing round the first idea that came to him. He wasn't interested in the idea, and he didn't care about the job. He just went on writing until he had written the eighteen hundred words that his friend needed, letting the pen run over its appointed space. Then he stopped.

His friend thanked him for the stuff, and used it to fill those two columns among the advertisements, publishing it under an assumed name. It wasn't a short story; it wasn't a character study; it wasn't a situation; it wasn't a sketch; it wasn't a transcript of a mood nor a spiritual adventure arrested in a moment of vision; it was nothing. It had no beginning, a blurred middle, and no ending. It was a blob of the protoplasm of negligible.

And lo, the critics seized upon, that issue of that paper and fell upon that pale attenuated burbling, and announced the discovery of a writer who had found for the conte an entirely new genre.

And now, the poor wretch who wants to tell straight, vivid, moving stories has to earn his living by burbling.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now