Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Defense of the Debutante

In which One is Wooed, Pursued and Finally Won by Another

GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

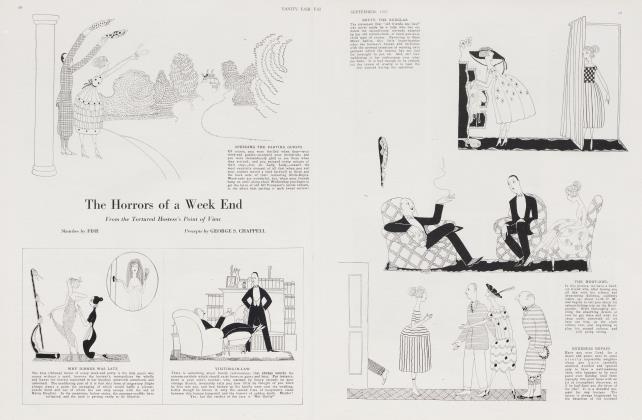

AMONG the imposing clan of beings known as the matrons of society, by far the most popular indoor sport of the day is that of slamming the younger generation. The debutante is their special prey. My word! how she is raked over the coals. In any gathering of two or three ladies of uppermiddle age, all ancient topics go by the board in favour of criticism of the debutante and all her works.

This is very distressful to one who admits a decided penchant for the 1921 model. She is a form of mental and physical exercise, violent perhaps, but far more enlivening than pulling literary chest-weights with dull high-brows who can hardly lift their own chins. Often I am tempted to step forward and say, "Far be it from me to stand silently by, while a woman's fair name is at stake." It is a good line. Unfortunately matrons are impervious to emotional appeal. Their mental motors are dead. Their answer would be wall-eyed disdain. Consequently I frequently do 'stand by', raging furiously, my blood at the boiling point.

So great became my worry over this question that, after much thought and with great hesitation, I decided to take it up with the great Professor Freud himself, the fountainhead of wisdom in all such matters. Addressing him at his famous laboratory in Vienna, I despatched a long letter and anxiously awaited results. Imagine my delight at receiving a comprehensive reply sent economically by night-cable. Freely translated from the original Swiss, it reads as follows:

"Referring to matter of present-day peeve of leading lorgnettes toward younger generation, reaction is world-wide. Condition due entirely to resentment of older ladies at existence of pleasures denied their own experience. This mental attitude known technically as 'sensory disappointment' or, more accurately, 'introverted complex of thwarted desire', results in extreme severity and exaggerated functioning of critical faculty. Wish you were with us.

"Siegmund."

How marvellously this fits in with my own experience can only be illustrated by the relation of an incident in which this entire matter was brought very graphically to my attention.

As I have said, this unwarranted attitude of the chaperone-class frequently raised my temperature to a most alarming extent. It was while in this irate frame of mind that I recently ran across Herbert Nimms, who used to try to teach me Fourth-Farm Latin at school. His efforts in this direction were so entirely unsuccessful that he later abandoned the classics and is now a member of the faculty at "Windover", the fashionable girls' school, where he teaches a little psychology, looks pleasant and gives kind advice to sub-debs.

The occasion of our meeting was a large dinner dance, and I was, as I have said, at the boiling point, the immediate cause being the volleys of criticism which were being hurled at a particularly lissome young lady who, ever and anon, flitted into the field of vision. To me she was a dream of beauty. Her dress was a poem—a short poem, to be sure, but still a poem. Laughter bubbled from her lips, gaiety shone from her eyes and radiant youth gleamed from her flashing arms, curving neck and roseate lips. But what a barrage was laid down when she came within the zone of fire of that masked battery of matrons. "Who is she?" they demanded harshly. "Did you ever see such a dress?" "There ought to be a law against such dancing!"

Raging furiously, I wandered toward the punch-bowl, where I met Nimms.

The Conference

AS OUR hands met and his eyes flashed welcome, the realization swept over me that here was the man who, above all others, could calm my chaotic mind.

"May I have a word with you?" I asked. "I have something on my mind."

His answer was characteristic. "Have you anything on your hip?"

To my affirmative nod he observed calmly, "I can cure you", and silently led the way to the library where, in two comfortable chairs, we proceeded to operate.

"Nimms," I said, after the anaesthetic had begun to perform its blessed office, "you are a psychologist. More than that, you are a teacher of girls. In your hands is entrusted the character of formation of many of our loveliest young women. You see them at close range—you study their minds, you know their habits. Tell me, am I wrong in thinking that they are, in the main, better, brighter, and more beautiful than ever before, or am I to believe these carping criticisms I hear on every hand. These accusations to the effect that they smoke and drink and -"

"They do drink," said Nimms reflectively, harmonizing the thought with appropriate action. "A little—of course it is hard to get. There is a girl from Louisville in the Junior class whose Uncle sends her-," he hesitated, "presents—once in a while."

How well I saw the school-master in him then. They are princes of pussy-footing.

"Be frank," I urged. "I am worried over this matter. I have many young friends who have only lately made their entry into society. We used to say 'made their bow,' but that is not done any more. They merely cock their hats, kick up their heels and say 'Ooh-la-la'!"

"They do kick up," he admitted. "There is a young lady on the basket-ball team who —but go on; I am interrupting you."

"No, no," I protested, somewhat confused. "I am doing all the talking—and I should rather hear you talk. But first let me give you my idea. You know the modern girl. You realize what she is like—a wild, spirited, coltish creature. According to her most savage critics, she i$> everything abominable. According to others—but never mind. Here is the point. Whatever she is, immodest or merely honest, rude or merely frank, wild or merely young, isn't she, after all, what we of this generation have made her? Can't all her vagaries be accounted for in some perfectly normal way? They say she drinks—what can we expect under the present prohibition law? They say she goes joy-riding at two A. M. Who supplies the motors for these young folks? They say she dances like a bacchante. Who first took her to the Greenwich Village Follies? Isn't there a perfectly logical reason for everyone of her qualities?"

"There is," said Nimms decidedly, "but before I reply more fully I must ask one question which you do not have to answer unless you choose."

"Fire away," said I.

"How is your hip?" he inquired. There was still a slight swelling which we relieved before my friend continued our conference.

"I have noted among our girls at Windover many of the tendencies of which you have spoken, and I may say I think we are perfectly in accord in our opinion of them. Some people object to cheek-to-cheek dancing. Personally I have always felt that in dancing, as in many other things, two heads were better than one. As you suggest, many actions which seem extreme are the natural results of a training which starts with the cradle. We teach our children to reverence ancient art, we read them the Ode to a Grecian Urn, we lead them patiently through the Metropolitan Museum and teach them the beauty of the nude, we administer culture via Mordkin and Pavlowa. Should we, then, be surprised that they are imitative? There were two young ladies in the Sophomore class who used to practise classic dancing in the moonlight, against a background of sassafras-trees—I fell off the fireescape."

The Real Reason

"THEN why," I argued stridently, "why in the name of common-sense should our older ladies purse up their lips ? Why do our matrons mew so furiously?"

"Shake not thy gory locks at me," he admonished. "You do wrong to accuse them; you should pity them-"

"Pity them!" I snorted. "I detest them. There is a girl here to-night-"

"You are wrong," he continued. "They should be pitied. Did you ever meet my wife ?"

"My dear Nimms," I cried, "I did not know you were married."

"I am a widower," he said solemnly. "My wife was many years my senior. Last winter, the flu—'de mortuis nil nisi' you remember."

"Quite so," I agreed. "Nevertheless," he continued, "I could not help noting the tendencies to which you refer in Mrs. Nimms. She was; in fact, what I should call Type A, Serial Number 1 in the critic-class. She was a large woman, very wealthy by the way"—I pressed his hand silently—"and, when aroused, distinctly devastating. The sight of a debutante roused her to a pitch of excitement which I have only seen equalled by that of a tigress in the Bronx Zoo when the keeper brings a large chunk of raw meat toward the cage. She fairly howled. It was in these moods that I used to study her in the light of modern, scientific psychology. As I considered her past history, her childhood and its environment, I suddenly hit upon the key to her remarkable ferocity. Her father was a smart Baptist who supplied the Bibles that go in hotel bed-rooms. He discovered that about sixty-four percent of the hotel-guests stole the Bibles from the rooms, so that there was a steady demand for his product. In that way, he built up a colossal fortune.

Continued on page 84

Continued from page 58

"But you can imagine my wife's background! It was horrible. Life was just one blue-law after another. Everything was forbidden. Dancing, cardplaying, flirting, speaking at the table —and as for drinking or smoking—ye gods! Well, you can imagine how she felt when she saw the young people of to-day having a good time. Every unfulfilled desire, suppressed wish, playimpulse, pleasure-hungry and thwarted ambition of her girlhood was thus flaunted in her face! It was terrible. Her bitterness was only a pitiful attempt at a rationalization of her own disappointment. So it is with all of them—and there you are, old priceless."

Nimms rose and I followed, a bit unsteadily, for I felt as if dazzled by the bright light of revelation with which his accurate diagnosis had flooded mv mind. As I glanced toward the coterie of chaperones crouching on the sidelines. looking as if thev lived on a diet, of ten-penny nails, my heart softened within me. Just then the lissome dancing lass floated across the floor.

"There she is!" I cried. "That's the girl they were all criticizing!"

Raising his voice slightly, mv friend called: "Mildred."

The star-eyed vision swam toward us. "My daughter—step"—he elucidated.

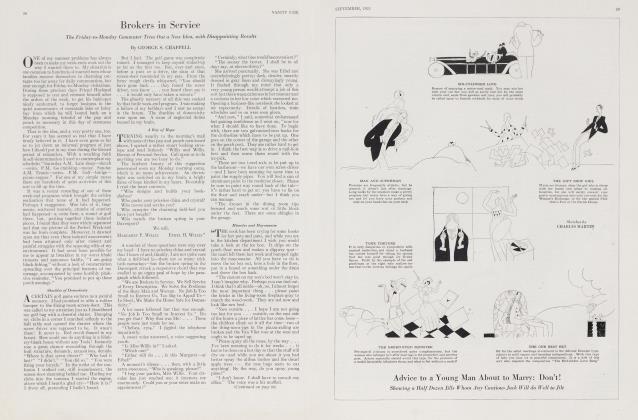

When the presentation took place, I was not looking my best. In fact, I appeared to be giving an imitation of a goggle-eyed perch. Things were coming a bit too fast for me, but I gradually recovered. She was adorable. Her make-up, even at close-range, was absolutely perfect. And as for dancing! For a moment it gave me a cruel sort of pleasure to steer as close as possible to the group of matrons, but their composite expression of severity again melted me to pity and I mercifully led my exquisite partner into the dim recesses of the library. Shall I ever forget the joy of the rest of that evening! How we danced and laughed and chatted, occasionally reporting to good old Nimms, who smiled paternally upon us. All the bitterness had gone from my heart. In its place resigned an allpervading love of mankind,—if Mildred could be so called.

It was naturally a fearful shock when I opened my mail a week later and read the following from Nimms:

"Dear Old Boy, Realizing how thoroughly you appreciate the debutante of to-day, I know you will congratulate me upon my engagement to my stepdaughter Mildred. This sounds a bit queer, I know, but it isn't. In fact, our manage in the past has really been rather more unconventional than it will be in the future. The arrangement will have the practical advantage of keeping the Bible-money in the family. In any case, I want you to be my bestman, a position for which you can easily qualify, as there aren't to be any others."

"The great goof!" I thought as I laid down the note, and then the crushing symbolism of the situation struck me with its full ironic force.

Victorious youth dancing down the path of life and the late Mrs. Nimms revolving rapidly in her earthern cell!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now