Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDisappearing Localisms

FRANK MOORE COLBY

The Trouble with the Aristocratic Circles in American Novels is that They are Devoid of Aristocrats

THE familiar way people are using the term "Main Street" usually for purposes of abuse, but at any rate as definite characterisation, adds a convenience to the language. Everybody understands what is meant by the Main Street sort of thing, even if he has not read the book, and it comes at a time when such symbols are much needed, for the confusion of characters following fusion of race and class in this country is fast taking all sense or point out of once useful localisms. I suppose every one has noticed the fading or lost significance for literary, facetious, or vituperative purposes of such terms as Boston man, Chicago, Kalamazoo, Oshkosh, very Western, New York smart set, backwoods, Red Gulch, Plunket Hollow, Knickerbocker. Boston man, for example, though the term still lingers as a curse, obviously applies no longer to Boston, the Boston man in this sense of the word being at the present time probably in Omaha, in some literary club. And what definite notion could possibly be called to any one's mind by the expression a "thorough New Yorker"? It seems probable that every famous local type is now found in some other quite distant locality.

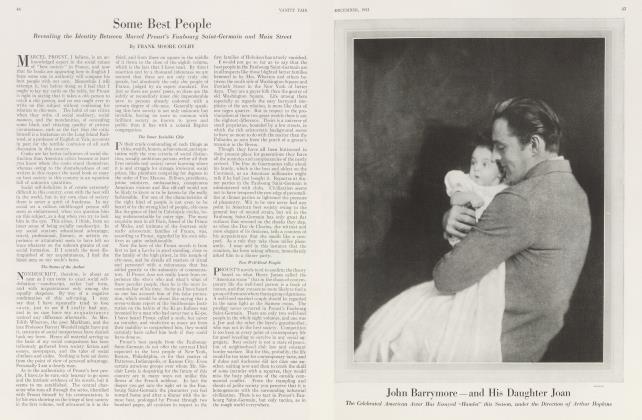

As to aristocratic or fashionable local terms I suppose our case is hopeless, terms, that is to say, like Belgravia, Mayfair, Faubourg Saint Germain, and many others, which whatever may have happened to the quarters themselves are still employed definitely in the very latest books—Belgravia having recently been found by Mr. Harold Begbie to be just as it was when Mr. James Yellowplush saw it, and the denizens of the Faubourg Saint Germain standing out quite as distinctly after the last analysis of M. Marcel Proust as the Hopi Indians after thorough anthropological reports under the auspices of the .Smithsonian Institution. The idea of social miscellany is now, of course, inseparable from all the New York streets and quarters that once served this purpose in the American novel.

Aristocratic New York

TAKE, for example, the canaille of artists, writers, actors, clerks, Grand Central Station rag tag and bobtail called to mind by such terms as Washington Square, Gramercy Park, Murray Hill, etc., or imagine a young man giving a Fifth Avenue address in the old complacent manner, when the chances are ten to one that it will brand him as a Lithuanian garment cutter or the father of eight Italian children or some creature with hardly a footing even in this hemisphere, to say nothing of a social standing in the town.

To be sure New York suffers from a double evanescence in the matter, for not only do the quarters change beyond all social recognition, but the novels about them are of a kind that pass almost instantly out of mind, Van Bibber characters disappearing from the memory faster even than Van Bibber houses vanish from the street. New York fashionable quarters have always been torn down in fact before they were built in literature, and it is only by the unaided powers of your own mind that you can attach an aristocratic interest to them, or indeed any interest at all. Some say the shape of the island is to blame for the instability of the New York social term, but it is no more to blame than the shape of its fiction. If Washington Square does not linger in story and song it is certainly the fault of the story and the song, for a novelist might have invented the right sort of people, even if the right sort of people could not be found. It is not the fault of geography, if every local term supposed to be associated with the gentry is merely associated with ennui.

No quarter of any city, even of Paris or London, would long remain idealistically aristocratic if left to people like the late Richard Harding Davis or Robert W. Chambers. Nor would it fare better if the hard', cold gaze of Mrs. Edith Wharton, in the Age of Innocence, were turned on it, ruthlessly determined that nobody who lived in it should seem a bit more interesting than he probably was. Snobbery in New York has had no literary confirmation, and from the contemplation of its best society in the books, envy and a sense of exclusion never arise, except perhaps in the bosom of some colored man. Snobbish readers remain uninformed as to what to be snobbish about.

The Need for Lying

IT is no excuse for New York fiction to say in the stock phrase that fashionable life is "empty," for of what use is a poet or a novelist if not to people the inane? What with tedious melodrama on the one side and sheer photography on the other, New York writers would have created an emptiness, even if there had not been one. So it has come about through the literary destitution of the city that, with the best will in the world, one cannot entertain any agreeable illusion about its better class, never having encountered in any book an exclusive circle that one desired to enter, but only exclusive circles that seemed rather quarantined by the rest of the town than excluding it. New York fiction fails completely to account for the socially ambitious. Any person who desired to enter the upper circle described in Mrs. Wharton's Age of Innocence was not socially ambitious but simply morbid. You might as well call a person a social climber for wishing to enter a state institution for defectives. Not that I doubt Mrs. Wharton's veracity. On the contrary, the difficulty probably arises from her excess of veracity. By mystification and a little lying she might have created a social cachet that would have left room for envy and ambition in outsiders. Paul Bourget would have done so, and even H. G. Wells. Persons of great literary talents in other capitals are adding constantly to the myth that people who ought to be aristocratic really are so. In New York when we turn Robert W. Chambers and the movies on them to that end and then let Mrs. Wharton blast them, naturally there is not much left.

So we have no convenient local symbol of the upper class, and when you think of New York best society you never think of any name of person or place; you think only of an income. Incomes are the only symbols of New York gentilities and social nuances that are generally understood, like the quarters of London and the Faubourg Saint Germain. That a hundred years of novelists, society writers, and reminiscent essayists, often credulous of social distinctions and even adulatory, should have left us nothing but this dry arithmetical methodof classifying the New York better sort is one of the city's tragedies. Unaided by any traditional associations of desirable manners, breeding, point of view, exclusiveness, social charm, and prestige, aristocracy in its most delicate shades is arithmetical. It is not that we wish to take this commercial point of view, but literature has created none better, the term three hundred thousand dollars a year having as much literary value as social descriptions by the late Richard Harding Davis and his successors, and appealing even more strongly to the reader's imagination.

Indeed, it is a wonder that writers on New York have not battered the wider meaning out of every local term, and we ought to be thankful that they have left us the few general symbols that remain, such as Wall Street for sin and shame, Brooklyn for rusticity, Harlem for distance, Bowery for low life. As to high life, jumping about the city like a neuralgic pain, it will have to be left to the local diagnosticians of the moment, and will probably best be indicated in the long run by the names of new hotels, or automobile models.

Nor do Beacon Hill, Back Bay, and other Boston terms serve any better than Washington Square, in spite of their better luck in novelists. For despite all that Mr. Howells has done for them—perhaps on account of it— these symbols indicate a meticulous and fussy people, haunted by thousands of little cares, social, moral, educational, rather than possessed of the large, pig-headed aristocratic assurances—nests of mere academic vermin, never a butterfly. Mr. Howells's Boston aristocracy was the Cambridge set, contributors to the Atlantic Monthly, most of them.

The Spirit of Liberalness

AT any rate, the making of a Howells Boston hero into a contributor to the Atlantic Monthly would be about the best that Boston birth and breeding, as described by that novelist, could have done for him. Like Mrs. Wharton, he would not give his imagination a chance, but let the facts control it. If he had created a gay unscrupulous Beacon Hill seigneur or Back Bay sad dog, his conscience would have troubled him. Perhaps such a thing would have been impossible in Boston. Still I believe several generations of Ouidas might have made something out of the place, or the elder Dumas working with his eyes shut.

Pertinacity quite as much as literary skill is required to fix a localism in the language so that it lasts independently of what happens to the place or the people in it, such as buncombe, billingsgate, first families of Virginia, brummagen, Bayswater, and I hope, Main Street, for obviously nobody cares whether Buncombe County is still patriotic or whether there are any first families in Virginia or if the needless unanimities of Main Street are just as common in the Sixties and Seventies east of Central Park. It is a mistake to discard a local term that has a good start like Greenwich Village, for instance, simply because recent investigations have proved it respectable, or because worse one-act plays are now written at Harvard,' or because the "advanced ideas" are more characteristic of the InterChurch Union for raising Cain, while Greenwich Village was in a fair way to render these useful verbal services, if people had let well enough alone. And now only movie producers can use the term with confidence. Conscience is always bringing facts to light and destroying these useful images, thus arresting the growth of the language.

(Continued on page 98)

(Continued from page 52)

This spirit of literalness might be fatal anywhere. "When one member of a family," says M. Proust in his latest novel, "emigrates into high society—a unique phenomenon, as it seems to him —he descries around him a terra incognita, visible in its slightest shadings to all who inhabit it, but a mere blank to those who do not penetrate it. To Swann's cousins his social connections were completely meaningless. Only one of them, whose family was about on a par with the Rothschilds appreciated that circle and was jealous of him. And at this moment he was by way of being one of the most correct persons socially speaking in all Paris." Yet M. Proust continues to use the expression Faubourg Saint Germain with perfect confidence—for this terra incognita.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now