Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThree Brilliant Young Novelists

No One of Whom Is Over Twenty-five

JOHN PEALE BISHOP

THE years following the war in America have been remarkable for the rise in popular and critical estimation of a small group of novelists, who represent a revolt against the silliness and complacency of commercialized literature. Although Mr. Floyd Dell, the youngest among them, approaches thirtyfive, they have been commonly referred to as the younger American novelists, the reviewers believing, no doubt, that any worthy who had not hitherto reached their notice must be young. Most of them are, alas, middle aged; one or two, perhaps, prematurely old, grayed by their years of obscure toil. There are, however, three young American writers each of whom is publishing a book this fall who cannot be overlooked by anyone interested in delivering the American novel from the Philistines. The sum of their ages is 72 years; each is a graduate of one of the eastern universities; each is trying to find some other solution to life than that offered by Dr. Frank Crane and Dr. Henry Van Dyke.

Francis Scott Fitzgerald is a Princetonian, Stephen Vincent Benet, Yale '19, John Dos Passos, Harvard '17. Being myself a graduate of Princeton (present at all reunions in orange and black costume), I will first consider Mr. Fitzgerald.

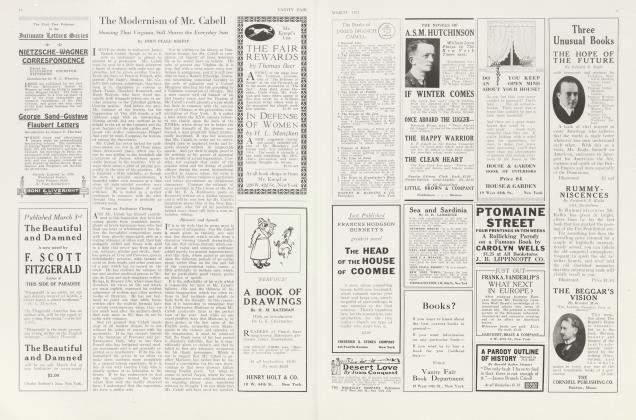

Princeton 1917

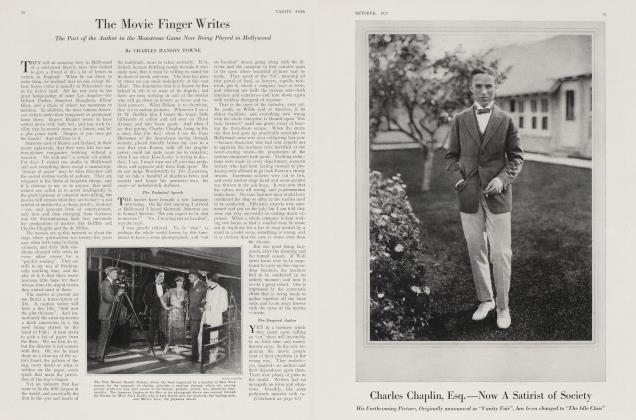

MR. FITZGERALD'S novel, The Beautiful and Damned, is to run serially in the Metropolitan and later to be published by Scribners. It concerns the disintegration of a young man who, at the age of twenty-six, has put away all illusions but one; this last illusion is a Fitzgerald flapper of the now famous type—hair, honey-coloured and bobbed, mouth rose-coloured and profane. The minor characters are exhibits of popular stupidities—a reformer, a theosophist, a movie director—burlesque masks behind which may occasionally be seen a shadowy figure with the eyes and lips of Mr. H. L. Mencken.

The humourous portions of the book are exceedingly good, perhaps the best thing Mr. Fitzgerald has done. The satire is deftly and wittily handled, but in spite of the left-handed happy ending the book does not achieve the irony which the author has clearly intended; its mood is rather one of first cynicism.

But, as with This Side of Paradise, the most interesting thing about Mr. Fitzgerald's book is Mr. Fitzgerald. He has already created about himself a legend. In New York I have heard hints and from Paris stories which it would be discourteous and useless for me to repeat. The true stories about Fitzgerald are always published under his own name. He has the rare faculty of being able to experience romantic and ingenuous emotions and a half hour later regard them with satiric detachment. He has an amazing grasp of the superficialities of the men and women about him, but he has not yet a profound understanding of their motives, either intellectual or passionate. Even with his famous flapper, he has as yet failed to show that hard intelligence, that intricate emotional equipment upon which her charm depends, so that Gloria, the beautiful and damned lady of his imaginings, remains a little inexplicable, a pretty, vulgar shadow of her prototype. But the book should allay the fears of anyone who has had fears for Mr. Fitzgerald's ultimate commercialization which appeared imminent after Flappers and Philosophers. It is an honest record of one of the most interesting minds of his generation.

Yale 1919

STEPHEN VINCENT BENET has already published three volumes of verse, Five Men and Pompey, Young Adventure, and Heavens and Earth. If The Beginning of Wisdom is his first novel, it is certainly not his last, for Jean Huguenot is already completed and a third novel is in preparation—all this at twenty-three.

The Beginning of Wisdom (Henry Holt) is a picaresque novel of a young man who successively encounters God, country and Yale. Mr. Benet treats Yale as something he remembers rather than as something lived through by his characters. He has, too, been a little too well bred about it for all his jibes at the pious athletes and the impeccable parlor snakes. The only way to make literary material out of one's youthful experiences is to be shameless about one's self and ruthless with one's friends. Mr. Benet has concealed nearly everything about himself except his opinions, and what he has had to say about his friends has been said with wreaths tied with Yale blue ribbons. The unfortunate part about it is that no one at that age particularly minds being made stock of. Fitzgerald made a Princetonian figure in my image and thrust it so full of witty arrows that it resembled St. Sebastian about as much as it did me. I was undeniably flattered. Mr. Benét has visualized Yale, but he has not dramatized it. The only incident which has a present air has not to do with the college at all but with the daughter of a dilapidated dentist of New Haven. Amourously entangled, the hero marries her. A few weeks later she dies. Clearly, they order these things better at Yale. In Princeton such adventures seldom end in marriage and when they do the women live on forever,

(Continued, from page 8)

Mr. Benet is a much better novelist when not retracking too closely his own footsteps, and throughout he has the courage and skill to write beautifully. He has so rare a skill with colour, so unlimited an invention of metaphor, such humourous delight in the externals of things, so brave a fantasy, that he occasionally forgets that the chief business of the novelist is not to describe character but to show it in action. I am not quite sure what is intended by the beginning of wisdom—but it is certainly not the fear of the Lord. For a while, the hero seems to look toward beauty and arrogance and irony for direction in all things, but in the end he marries a girl who has been with the Y. M. C. A. in France and returns with strange ideas of "service and sanity through service",

Where are the eagles and the trumpets? Buried beneath some snow-deep Alps.

Cis-Atlantic Warfare

FITZGERALD, Benet and Dos Passos belong to the generation which suffered the actual indignities of war. In each of these novels we will find an approach to the war quite other than that found in the soldier stories which three years ago begawded our magazines.

It is perhaps no mere coincidence that all our better known war stories were written by women; Humouresque by Fanny Hurst, the rhythms of Grand Street reduced to a violin solo—a tribute to sacrifice paid with a wreath of white carnations left over from Mother's Day; England to America by the Montague lady with three names—Hands Across the Sea, annotated for New England spinsters; Edna Ferber's homely romances—sugared doughnuts served on a service flag; the Sergeant Gray stories of Mary Roberts Rinehart—accurate information on the routine of a division headquarters troop dispensed through a detective story technique. At all events, it was the feminine attitude toward war which found popular favor in the troublous years from 1917 to 1919. The contributions of the older men writers we will pass over in silence. The younger men were either driving ambulances or doing squads right. Later came a revulsion toward war stories of any kind, possibly because readers were a little ashamed of the cheapness of their inflated emotions. Mr. Fitzgerald, when he wrote his first novel, judiciously omitted any actual references to the army, but both in his present volume and in Mr. Benét's there is unashamed treatment of life in the American forces. Mr. Fitzgerald served nearly two years as an officer in the regular army. He now takes occasion to deliver a merciless satire on the stupidity and pompousness of West Pointers and the discipline of training camps. His satire is as rapid as target practice on a rifle range and bitter in the mouth as sand blown over a parade ground,

Mr. Benét's experiences were likewise Cis-Atlantic. Book VII of his novel, written with the impudent buoyance of the early days of the officers' training camps, includes a series of portraits— officers, men, artillery horses, and guns —and one conversation of most unsoldier-like speech on immortality. No less than the Yale section it shows Mr. Benét's tendency to treat incident visually instead of dramatically. But it also shows with what skill and humour he can evoke physical details,

Harvard 1917

SEEING how these two studies of army life stand out by sheer honesty army by from previous attempts, it is difficult to speak calmly of John Dos Passos' Three Soldiers. However viewed, whether as a novel or as a document, it is so good that I am tempted to topple from my critical perch and go up and down the street with banners and drums,

Here, once and for all, is the very stuff and breath of that strange thing which was the American Army of 1917-1919. The burdensome discipline of the training camps, the unutterable boredom of billets and hospitals, the filth and terror of fight, the dizziness and gay abandon of spring in Paris. He has evoked the American soldier, alive and individual for all the effort to press him into a mould, a young man with the helpless, lovable charm of a child and the uncontrolled viciousness of an animal. His speech is here, with its unceasing obscenity and its hatred of affectation.

Three Soldiers (Doran) is a story of Fuselli, an Italian of the second genera tion from San Francisco, eager to adapt himself and to get on in the army; of Chrisfield, a wild-angered, lovable boy from an Indiana farm, and of the East ern John Andrews, insurgent in thought and passion, but outwardly tamed. The background is filled with figures-officers, soldiers, French peasants, Y. M. C. A. workers, cocottes, Parisian aristc crats. I know of no American novel of this generation in which so many minor characters, each unforgettable and perfectly placed, appear and disappear without confusion. Mr. Dos Passos, realizing that two of his principals at least were unusual characters going toward unusual fates, has contrived to silence criticism by placing against his protagonists, in each crucial moment, an ordinary soldier with quite normal reac tions. Despite the technical difficulties of carrying three major characters the book has the firm structure of steel.

If it were only that Three Soldiers is the first complete and competent novel of the American Army it would deserve great praise, but it is more than that, for, in Mr. Dos Passos' hands, the army becomes a symbol of all the systems by which men attempt to crush their fel lows and add to the already unbearable agony of life. Here is more than an honest record of young men's lives: here are the tears of things, the shadows of the old, strong, unpitying gods lying across the paths of men; anger, and hate, and lust are here and laughter~and the manly love of comrades, and at the end, resignation and despair, the return of a bioody and hateful thing done in an autumn wood, the beautiful proud gesture of a man going down in defeat before life. And this is why I say that John Dos Passos is a genius.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now