Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAnders Zorn: Master Painter of the North

His Life, His Personality and His Artistic Characteristics

CHRISTIAN BRINTON

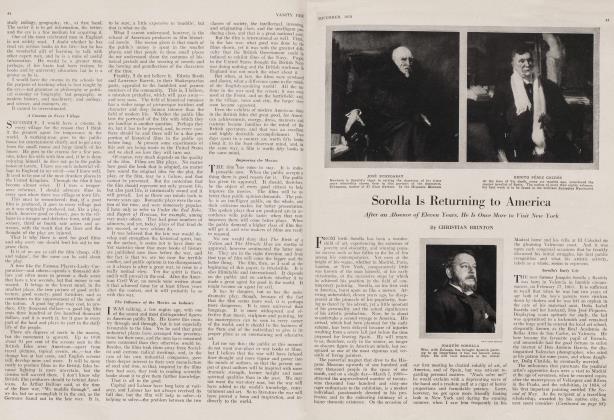

THE romance of actuality is seldom better exemplified than in the career of the late Anders Zorn. Bom in a remote corner of the earth, the son of an itinerant Bavarian brewer and a Swedish peasant lass, he became the friend and favourite painter of king and president, and a figure of international prominence in the field of art. Unlike so many of his colleagues, who are fated to await recognition long deferred, he was successful from the outset, and continued so to the end. In so far as possible upon this mundane sphere, all his ideals and ambitions seem to have been realized.

The obscure boy who began by carving statuettes of animals out of birch wood with a rude clasp-knife, and tinting them with berry juice, lived to see his work welcomed by the most important art institutions the world over. His first professional recompense consisted of a loaf of black bread and a copper tendered by an appreciative peasant farmer in payment for a crude but expressive figure of an insurgent cow. He died leaving a substantial fortune and a testament notable for its enlightened liberality.

Remarkable as was his career, there were two specific reasons why the lad from Mora should have risen so far above his early station. The first of these was his own native endowment, his birthright of abounding health and instinctive delight in what are designated as the good things of earth. Zorn's boyhood was passed mainly at Utmeland, near Mora, in Dalecarlia, the heart of Sweden. Like his comrades, he tended the flocks or spent serene days on Lake Siljan. A typical "Morakulla," his mother, and his grandmother, the faithful "Mormor," of numerous etchings and paintings, came of the sturdiest native stock. And it was with this incomparable capital that the lad embarked upon a profession in which sheer physical energy and the worship of bodily vigour and beauty were destined to play so conspicuous a part. "Lill' Anders," as he was called, was normal and frankly objective in his attitude toward the world of sight and sensation that surged about and within. He possessed none of the passionate mysticism of the youthful Segantini who grew to maturity among the solitary foothills of the Alps. He saw no visions and dreamed no dreams—none at least that were not readily attainable.

Continued on page 96

Continued from page 42

Innately eclectic and assimilative, Anders Zorn was one of this brilliant coterie, and, like them, acquired a freedom and spontaneity of theme and treatment that were evinced in every phase of his production. Possessing a marked feeling for plastic form, he at first intended to devote himself to sculpture, but even before leaving the Stockholm Academy he had made a reputation as a clever exponent of aquarelle. To his work in water colour he shortly added the freedom of the etcher's needle, and by five and twenty was an accomplished craftsman in both media. Though he never became an impressionist as regards actual technique, Anders Zorn was quick to absorb the spirit of impressionism,—that informality of viewpoint and rapidity of notation which are its essential characteristics.

At the very outset of his career his nominal headquarters were to be found in London, where he supported himself by selling water colour sketches, and mastered the technique and practice of etching under the savant guidance of his distinguished countryman Axel Herman Hagg. Following this interlude, he lived for a considerably longer period in Paris, and it was in the French capital that he first met that official recognition which carried with it the promise of public appreciation and popular success.

For a decade or more Zorn painted in water colours only, but during the summer of 1887, which he spent at St. Ives, on the Cornish coast, he began to use oils. It is significant to recall in this connection that his first important oil painting, entitled A Fisherman, which was exhibited at the Salon of the following season, was purchased by the French Government and hung in the Luxembourg. With such an auspicious beginning honours came thick and fast. The succeeding year he was awarded a medal of the first class at the Exposition Universelle, a gold medal at the Salon, and the ribbon of the Legion of Honour. It is small wonder that the painter, who was still under thirty, should have been moved to take up residence in Paris, and it was in Paris that he began the series of oil portraits which includes the likenesses of Antoine Proust and Coquelin cadet, and the memorable set of etchings, among which the most notable are those of Renan and Paul Verlaine.

The Return to Sweden

FOLLOWING his flattering success, both personal and artistic, at the Chicago Exposition of 1893 Zorn rer turned to Paris, and, after three busy, remunerative years, determined to settle definitely in his home country and near the site of his modest birthplace. He accordingly built himself a spacious timbered house—a veritable Swedish gard—at Mora by the shores of Lake Siljan and proceeded to devote his energy to the portrayal of local type and scene. He had, in fact, never really lost touch with native inspiration and he now threw himself into the work with characteristic whole-heartedness.

An indefatigable collector, he filled his home with the choicest objects, domestic and foreign, and nothing was more delightful than to watch him display his treasure-troves with almost boyish enthusiasm.

It was not, however, his house that most interesting Anders Zorn during these happy, fecund days. He passed much of his time in his cutter, the "Mejt," on the lake or tramping through the forest where he would come upon a group of bright clad lassies tending their cattle in some sparse upland pasture or busying themselves about their humble cottages among the hills. A peasant himself he would attend rustic dances on the village green, watch the longoared church boats glide across the placid water on Sunday morning, or note the pagan glare of St. John's Eve bonfires redden the encircling sky. Dressed for the most part in the rough sheepskin jacket and knee breeches of a typical Dalkarl, he seemed far removed from the cosmopolitan painter of, Paris days, or the mundane portraitist who enjoyed such vogue in New York and Washington.

Brilliant and characteristic as are his likenesses of the conventional man and woman, the statesman, the industrial magnate, or the grande dame of the social world, Anders Zorn's chief legacy to posterity remains his series of out and indoor genre paintings and etchings, devoted to the rustic goddesses of Dalecarlia, the fresh-tinted lassies of Mora, Floda, Rattvik, or Leksand. Here is his true pictorial treasury, his most authentic claim to permanent recognition. No phase of these particular subjects has been overlooked. Here is a stalwart maiden clad in heavy sheepskins, bearing the foaming pails from the milking shed on a frosty January morning. There are a pair of full bodied females drying themselves before a ruddy log fire. The frank verity of such scenes is not the least of their attraction. In their presence we lose all sense of sophistication and selfconsciousness. The spectator's as well as the painter's attitude toward the problem in hand is not scholastic, not academic. It becomes spontaneous and refreshingly primitive.

And so with his innate zest for life constantly stimulated through direct contact with reality, Anders Zorn continued year after year to paint and etch the selfsame themes, to celebrate the sovereign strength and beauty of the Dalecarlian peasant. He may at times have thought of executing more consciously planned compositions. He may have wished now and then to get beneath the bright tinted surface of things, yet his work betrays no suspicion of inquietude, no hint of doubt or hesitation. He maintained to the last the same baffling speed, the same magic manipulation of light and shade, and the same clarity of colouration which recalls the freshness of his first water colour sketches made when a student at the Academy.

Based upon the rapid notation of external appearance, Zorn's art attracts the eye rather than the mind and the creative sensibilities. Dazzled by the man's technical virtuosity, you are likely, in surveying his sparkling canvases, and swiftly stenographic etchings to overlook certain less superficial considerations. Yet you must not demand in work so instantaneous that permanency of appeal which is the legacy of more deliberate methods. You here find a spirited transcription of visible reality, not an interpretation of life and nature in their more enduring aspects.

Whatever reservations one may be disposed to make, the fact nevertheless remains that Anders Zorn won for himself a lasting place in the • varied and sometimes puzzling panorama of modern painting. He takes his position beside ' the most brilliant among his colleagues, beside Sargent, Besnard, Peter Severin Kroyer, the Dane, and the dexterous Spaniard, Sorolla y Bastida. And, when he was stricken in August last, there were few who did not agree that contemporary art had lost one of its most picturesque and characteristic figures.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now