Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGauguin Revisited

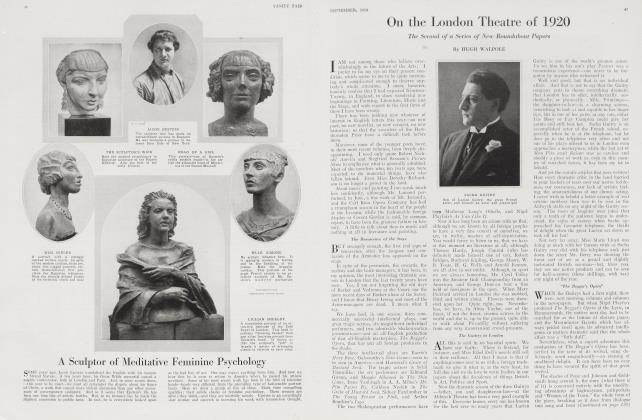

Fresh Light on the French Painter's Life in the Pacific

STEPHEN HAWEIS

FIVE years ago the man in the street knew no more of Paul Gauguin, the French painter, than he knew what Keats were. But now the white shadows of the South Seas have been explored and exploited; he has read W. Somerset Maugham's novel, The Moon and Sixpence, and now he knows all about Gauguin—wrong.

That Gauguin was one of the greatest artists of our time is now generally admitted. "He has been dead nearly twenty years (he died in the Marquesas Islands in the South Seas, in 1903) and his pictures sell everywhere for preposterous prices, so it is safe now to talk about him in terms of unqualified admiration.

Gauguin was a Post-Impressionist, and the father of PostImpressionism, but the ban is lifted upon the brood, and now he sits among the Gods upon the picture dealer's Olympus.

Society has had its thrill about the man who abandoned civilized Paris to play with strange women in the remote South Seas. We have read of those golden girls among the scarlet stars of the hybiscus and of purple nights where the incredible sea munches upon beaches of silver coral. The inevitable beach-comber has been fine-combed to good effect; and we find the rascals are as prolific of strange tales as they were when Robert Louis Stevenson plied them in the cause of letters with rum and tobacco.

And the strange tales are all true—in broad outline. Odd things happen every day in surroundings far from the beaten track; romance comes to meet the man who knows how to find it, but it is not confined to the Southern Pacific. Tales as strange may be heard from the beachcombers at Narragansett Pier, and there are strange girls nearer than Hivaoa, with savage instincts and superstitions, who will deliver up their secrets to anyone who knows how to search in the archives of their souls. Modern city dwellers cannot live in uncivilized places any more than heather will grow in a city window-box. Most people would be infinitely bored and disappointed in the lovely Masquesas, and many a misguided tourist to Tahiti has bewailed the fact that the steamers which can bear him home and away are so infrequent.

The Real Gauguin

BUT now that we have stripped every rag of reputation from the great master, who might have decorated and should have been allowed to decorate a noble building in some comer of the world, now that he stands naked upon every bookcounter, let us, in all justice, hasten to avow publicly that this is not the man of whom we read in The Moon and Sixpence.

Gauguin was never a stockbroker who rebelled suddenly against the routine of respectability. He was not a coldblooded monster with violent disregard for publicity and recognition. There is every indication that a moderate appreciation, especially if backed with a cheque book, would have been most welcome at several periods of his history. And he did not die of leprosy, attended by a faithful black partner fanning him with a banana leaf.

Having no private knowledge about Mr. W. Somerset Maugham, beyond what one who reads may run to, I feel sure that it was never his intention to blacken the name of a great artist. He conceived a character, and, by skilfully rolling the legends about several artists between his hands, and twisting them into manuscript, produced a work of art which was not meant to be a portrait of anyone in particular, though he used the local colour of Tahiti and heard the tales about the romantic figure in art who lived there for ten years.

Those who know a little about the life of the Master in Tahiti can easily understand how the material was gleaned from the street corner gossip of Papeete. Gauguin did find a Tahitian mate of whom he wrote in his book Noa Noa, and a house which he built at Punavia or Mataiea did burn down,—most Tahitian native houses do sooner or later, for they are made of reeds and roofed with leaves. He separated from Tehura, the lady of Noa Noa, and with other "lovers of a day" was carried away in a ship bound for France.

But he returned to the islands after a visit and later went to the Marquesas Islands, several hundred miles from Tahiti, where he died. He was never afflicted with leprosy,—we have this on the word of Dr. Chassagnol, the Chief Medical Officer of Tahiti, who was his physician and very good friend to the last.

It is natural that scandals should have arisen and that they should persist about one who flouted the respectable Colonial French official type to the degree that Gauguin did. He was a white man; worse, an educated white man, who "went native". No doubt he did everything to shock and offend Colonial society. He wore the scarlet pareu, or skirt, and his auburn hair grew into his beard and almost upon his shoulders. He would sit around with his native friends half naked while his compatriots walked in leather shoes and correct Colonial topee, or helmet, and white duck outfit. He loathed civilization as many of us do, but he was strong enough in his hatred to cast it off without regretting the infinitesimal comforts which bind most men. He lived, not as we pretend to live in these days of complete purity, but a missionary who was called to his deathbed shortly after his decease and was unlikely to be biased in his favour, was able to say that he was "un charmant homme" whose influence upon and on behalf of the natives was good, and ever on the side of right—speaking humanly and politically.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued, from page 71)

The police administration of the Marguesas islands was corrupt in the extreme in those days and the natives were exploited shamelessly . by . the French officials. Gauguin alone was their champion. On this page there is a letter which he addressed to his lawyer, one of half a dozen that he wrote, explaining his difficulties and demanding assistance on behalf of the natives against the French Government.

March 2, 1903.

Monsieur le Delegue des Marquises,

On account of the disasters which have recently burst upon our island and also on account of the famine which is to be feared, I come, in the name of humanity, to beg for the natives, who cannot defend themselves, not only legal assistance, but also pity.

Please accept, Monsieur le Delegue, the assurance of my distinguished sentiments,

Paul Gauguin.

The Death of Gauguin

IT was indeed the trouble he had over a matter of this kind, war against the local tyrant, which caused the clot on the brain from which he died. He was worried to death by the system of Society he tried to flee from, and the breath was no sooner out of his body than his enemy went through his house in an official capacity and searched his effects—incidentally stealing a few portable articles of vertu, among which was a walking stick handle, carved by Gauguin,—the excuse being that it was "obscene."

No doubt some auctioneer will discover these things some day, for it is not likely that they were destroyed. And these, alas, are not the only things which Gauguin created that are lost. It is said' that he wrote a long Mss. discussion of the four Gospels upon which he worked for five or six years, and another composition also was seen by several of his intimates called Conseils a ma fille, which was filled with witty utterance and poignant satire. Noa Noa shows sufficiently what Gauguin could do in literature. He was, like so many great artists, a brilliant amateur with his pen, and it is to be hoped that the Mss. will some day reappear.

Of the house he built in the Marquesas, nothing remains now but the swimming pool he dug and the frangipani trees which he planted with his own hand. He called it The House of Joy—and he wrote upon it a legend addressed to women:

Soyez mystèrieuses, et vons Serez heureuses.

The garden gate-posts were adorned with. two grotesque figures carved in wood—one a caricature of the local Catholic Bishop, and the other, I think, representing Saint Catherine. He did not love the Church, nor was he loved by it again, for he set up before his house in Atua, a figure of one of the ancient Gods of the islands, under which he inscribed, to the horror of the missionaries:

Les dieux sont morts.

Atua se meurt de leur mort. Truer word never was writ. The island people are dying fast—their Gods are already dead and the thin veneer of Christianity has done no more than stifle them. Their hearts are with the ancient Gods of the earth and sky and seas they know—and very soon all will be dead together.

One little anecdote may be recorded of Gauguin. A hurricane struck his island one year and a tidal wave washed away into the sea nearly the whole of the property belonging to a native neighbour whose ground abutted upon his own. The man was in great sorrow in consequence. Upon hearing his story, Gauguin gave him at once and outright a considerable portion of his own holding—nor was he content to give it with words alone. Knowing how the people were oppressed, he took the trouble to see that his title was properly secured by law, so that it could not be afterwards disputed and taken from him.

In O'Brien's book, White Shadows of the South Seas, we read that his grave is nameless and unknown. It may help to record that he was buried by the Roman Catholics—and therefore within their cemetery—no doubt there are some people living who remember where his body lies—and perhaps some day a stone may mark the spot where the great artist who, if he lived not perfectly, yet loved the natives, with a more unselfish love than the excellent officials and missionaries who have destroyed, beyond hope, a fine race of men whose very name may become nothing more than a myth, almost in our lifetime.

Throughout the earth the third-rate white man is like a blight upon the simple and uncivilized peoples, and none but the artists and a tiny percentage of the first-rate among us has even a shadow of regret or ever thinks of the hint of a remedy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now