Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRoadsters

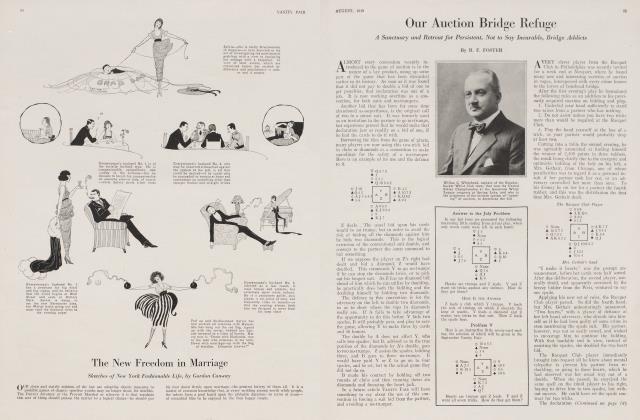

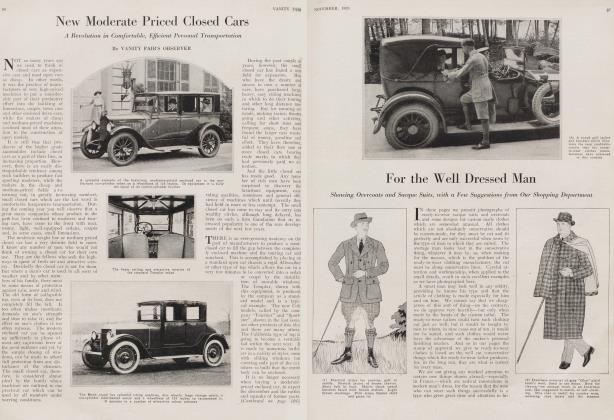

Their Development, Their Speed and Reasons for Their Permanent Popularity

VANITY FAIR'S OBSERVER

WHEN J. Henry Stonemace, the prominent cave man, first became prominent through the simple process of dragging more wives to his cave than his less progressive neighbors thought feasible and then sending those wives out to collect clam shells—thus creating the first great industry and the first labor problem—he cast about for something which would advertise his prominence. He found it in the roadster.

He had his huskiest wife tear a few limbs from an oak tree and build him a rough sort of chassis. Then, with a grapevine harness, he hitched the fastest from his stable of racing dinosaurs to the contraption and had—a roadster.

To his surprise, instead of being a source of expense for which he was amply prepared to foot the bill, the new machine actually more than doubled his business. He could drive his wives to work in the morning, call at noon and carry home their morning's crop of clam shells, and at five o'clock take them and the fruits of their afternoon's efforts back to the cave. It was an excellent arrangement.

It pleased the ladies. It helped them socially and physically. It allowed Mr. Stonemace to keep his eye on them during the trip home through the woods, which was always full of moral pitfalls. It allowed him plenty of time to search about, in style, for new and interesting mates. But its greatest advantage was one which the roadster has retained to this day—he needed no chauffeur.

Have you ever seen the streets of ancient Pompeii? They are streaked with deep ruts in the solid stone pavements. Those ruts were made by chariots—the Roman descendants of the one-dinosaur-power runabout of the Bivalve Kimono King—described above. The young bloods of those great old days must have made life a terror for pedestrians as they went dashing about the streets of the ill-fated city, making the rounds of the wine shops and baths. But, of course, that was before the days of Mayor Hylan and traffic courts and things.

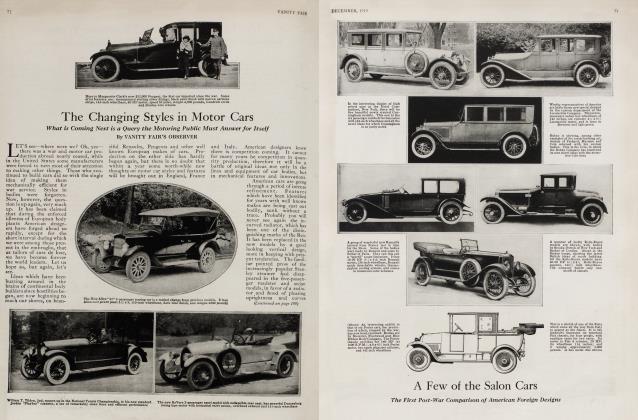

Always the roadster has been intimate, personal, fast, light, economical, durable — smacking of youth and adventure. The first gasoline-propelled road vehicle was a roadster; built by Carl Benz. It appeared on the streets of Mannheim, Germany, in 1885 and made seven miles an hour. Ralph de Palma just made almost 2 1/2 miles a minute in his Packard. The ignorant prejudice which lays the blame for all automobile accidents upon the motorist when official investigations have revealed that he is at fault in only 25 per cent, of them; which instigates widespread crusades against all motor car drivers and which impelled one New York City judge to take from the autoist $126,000 in fines in one year, was born with the roadster. Benz was allowed to run his villainous invention only on certain streets at certain hours.

It is a long cry from the wheezy, clanking Benz tricycle-runabout to the snappy, smooth running roadster of today. In these pages you will see the very latest examples of this popular type. It will probably be a longer cry from these cars to the roadsters of fifty years hence.

For the roadster has come to stay. In convenience and getabout-ability it is unsurpassed. The best brains in the industry find their widest and most pleasing expression in the roadster. It matters not whether you buy one of the cheapest of stock roadsters or get the custom body people to design one for you at great expense. In either case you will get something which will soon cease to be purely a pleasure and become a necessity; something that has speed, appearance, endurance, chumminess; that costs comparatively little for upkeep; that gives big returns and represents a good investment, financially and from a health standpoint.

(Continued on page 72)

(Continued from page 57)

Above all, the roadster is "sporty." And, as long as there is youth in the land, the roadster will be popular.

The inventor is naturally a mental adventurer and the roadster is expressive of that fact. The first airplanes were essentially roadsters of the air. The big passenger-carrying 'planes came later. The first motorboat was a sea roadster, followed later by the cruisers and cabin boats. No country has a monopoly of courage, so it came to pass that even before Benz began to frighten, timorous folk in old Mannheim with his early "stone crusher", an American was already embarked upon this then uncharted sea of research. This was George B. Selden, about whose famous patent tremendous volumes have been written. The main point here is that Selden's car, the first automobile in the world for which application for patent was made, was a roadster. Selden was first in the field, his application having been made in 1879. His machine existed only on paper but it covered all the essential principles of the modern automobile.

Imagine, if you can, a business man whose vision is so keen that he can see ahead for seventeen years. That is exactly what Selden did. He saw that the commercial development of the motor car would take at least that amount of time—the life of a patent—to become profitable. He had great difficulty, also, in interesting capital in his roadster. Therefore he did not press the issuance of his patent and it lay fallow in the patent office for sixteen long years.

In the meantime, Henry Ford, George Pope, of bicycle fame, and a number of other enterprising gentlemen, had caught the automobile fever and were covering our fairest highways with mechanical monstrosities, the gentle "purr" of whose motors sounded like "The Charge of the Light Riveters." Selden had encountered difficulties in actually constructing his machine. He gave up in despair more than once, because the vegetable and animal oils on the market did not lubricate but turned to black, gummy dough when exposed to heat and gave off an odor effective at eleven miles. Finally the Vacuum Oil Company created a mineral oil which did the trick and Selden's three-cylinder roadster became more or less of a reality—mostly less. True, the throws of the crankshaft, when finally delivered, showed a variance of something like twenty-five degrees, but he shoveled up the various parts of his engine, installed them in the snappy roadster body shown in the photograph—and one cylinder worked. The car ran, for a few miles at a few miles, with a delicate hum such as that on a still Summer night when you empty a barrel of nails down the laundry chute. The sixteen-year-old application had labored and given forth a patent and Brother Selden went out after Ford and the others, who, he figured, had infringed. The greatest fight in motor car history was on.

One court upheld Selden and he collected many rupees in royalties—but not from Ford. Then, a long time later, another court reversed the decision and royalties stopped, after which the patent ran out and the party was off. Today Mr. Selden is a disappointed old man with no love for Mr. Ford and a lot of others.

The result of this long-drawn-out war was the beautiful roadster of today. The primary idea of all these early workers was speed. Under the auspices of the Petit Journal, of Paris, the first road race in history was held in 1894. It was from Paris to Rouen, about 80 miles, and called forth 46 starters, twelve of them steam cars. Fifteen cars finished and the PanhardLevassor and the Peugot split the $1,000 purse, with the DeDion-Bouton steamer third.

The next year, in July, an American race was scheduled, with 42 entries. When the starter got his little pistol out, everything was "ready—except that only three of the cars had been built. The event was postponed until Thanksgiving Day, when five cars actually started, the Duryea winning over the foreign Benz in decisive manner.

The modern descendants of some of those old cars are very much in evidence today and will doubtless be seen in some of the revived road races in this country this year, notably at Elgin, Ill., August 11th and 12th.

No element of our great future motor car progress will be more popular than the roadster. For two or three people it can be made to fill almost every motoring need, and there can be no doubt that for some time to come the demand for this type of car will far exceed the supply.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now