Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Art of Jean Louis Forain

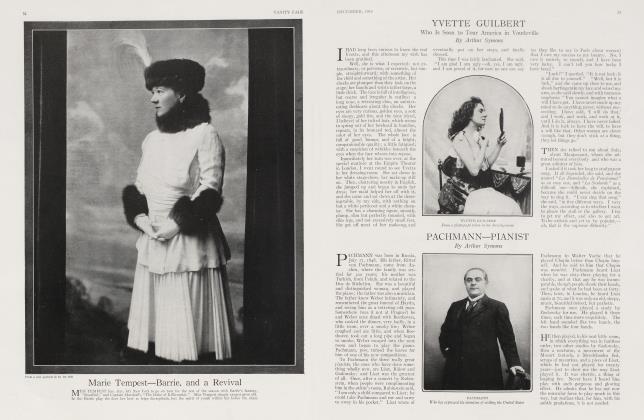

ARTHUR SYMONS

The Veteran Who Is Still a Master, as Well as a Popular Idol, in France

JEAN LOUIS FORAIN is, in some respects, the most picturesque figure in French art to-day. Although sixty-seven years of age, he was, throughout the war, in charge of the French camouflage corps. He and Steinlen rendered an incredibly important service to France. Forain's war lithographs

and military drawings were all of them admirable, but, if one wishes to see him at his best one must turn back to his pre-war period when he was interested in other things than war and warlike themes. Let us consider, a little, the art of Forain in the earlier days.

It is an art, derived first,—and slightly— from Carpeaux; then directly from Manet and Degas. Yet, in spite of those influences, his work is always original. Whether he draws or paints, in oils, in water-colors, or in other mediums, he is always startling to one's senses, astonishing to one's sensations. Take, for instance, the captious corruption of a drawingroom in a theatre, the tones of lights and shadows, the spices of the flesh, in one of his Pastels: and notice the extraordinary difference between this and a painting of a similar interior where the actress sits before her mirror: we see her begin her make-up; she tilts her head backward to see the effect of her hair.

Then imagine another, rather in the manner of Degas, where, in the wings a tall woman comes forward leaning on a man's arm; she wears a gorgeous dress and the other men, in eveningdress, move out of her way: all obviously enough aware of her professional smile. And the whole canvas lives, with disordered life; one feels it and one sees it.

DEGAS has painted the fascination of women's flesh, supremely. Forain, before the war, painted the Folies-Bergère, translated the whole horror and atrocity of the thing into a kind of carnival; showed the scene, the audience, the bars, the men and women, the sense of movement, of the heated atmosphere, of the very smoke of cigarettes.

And, again in a cafe, in a court, in a theatre—in the wings! The little painted dancers on tip-toe as they talk to a Balzacian Hulot who grimaces at them; one seizes snatches of their conversation, catches their gestures; one sees others gazing on them with envious eyes, or half-seen turning to one laughing faces. He can be cruel to them, satirize them, after the fashion of a splendid draughtsman who might once have been an 18th century Abbe.

Baudelaire was more learned, more perverse, more deliberate in his visualising the Vices than Forain. His technique is complicated. He has made extraordinary water-colors heightened with touches of oil, scenes in cafes, and in brothels and in the bars of music-halls. He gives one the sharp savourous scene of colors studiously spiced, and obtains, as he unites unimaginable effects, shades of a curious exactness, by the absolute science of an imaginative Alchemist.

So he paints women as women: this one with alluring eyes, with her cold and ambiguous smile, the glorious masses of her hair soaked in strange mixtures; with some of Lautrec's effects where some tinge of green finds its way invariably into flesh-color; where one sees something green in rouged cheeks, in peroxideof-hydrogen hair. But he never uses an aniline dye, poisoning nature, as Lautrec did; who, being tempted by tenebrous spirits, set himself to paint a green shadow on faces, on those of the people who sit night after night outside the cafes in Montmartre.

I have before me one of his finest etchings: Le quart d'heure de Rabelais. It represents a private room in a restaurant, seen just before the man and woman are preparing to leave. In the red-papered room one sees a divan; the man—a big, fat, ugly creature—is being helped into his overcoat by an uglier waiter, while the woman puts on her bonnet before the glass, scribbled over with names; exactly as in Rossetti's bit, when the man sees the woman's reflection—

"Where teems, with first foreshadowings,

Your pier-glass scratched with diamond rings"

And one sees, in the sordid aspect of this particular place, how the hired woman carelessly arranges her hair, as if she had totally forgotten the existence of the man who never looks at her; he, apparently stifled by the heat, looks at nothing, as he is tortured by the pulls of the—as one says in Argot—larbin.

FORAIN alone gives one the concentrated quintessence of all that passes on the boulevards* in Paris and of the interiors of cafes and of private rooms. Has not everyone noticed, in daylight, the banality of these rooms where one lives only at night, when all that is faded takes the peculiar tones of lights and shadows, with all the luxury and intoxication that one finds in Paris and in Paris only?

Le Cafe de la Nouvelle Athenes—by Forain—is superb —a vision of reality caught by, I know not what, inspiration. There is the angle, the tables, the glasses, the bottles, the match-boxes; there sit two men in tophats reading newspapers; top-hats are hung—as they always are—from pegs on the wall; there stands the hideous waiter in conversation with a cocotte, thin-waisted and perverse. And—so astonishing is the effect that this has on one—that I can easily imagine myself there, as I used to, so often, so many years ago.

(Continued on page 81)

(Continued from page 41)

Le Bar des Folies-Bergère is curiously different from Manet's. One sees the circular tables, the people seated, the living crowd that seems to move and that does not move; and a most singular view of the staircase up which vague figures ascend. The center is a Manetlike cocotte, fashionable, who holds her fan in her hand: one sees her black chignon, her smart bonnet; and she talks, of course, with an odious Gommeux whose fixed stare does not even disconcert her.

One, Le Cabinet particular, is magnificent in conception as in execution. It represents a room where the table shows that the three have dined: as in the wine-glasses, the coffee; one girl in chemise with bare arms sits on the edge of the table; black curled hair falls across her face, as the other who leans her head on her hand, elbow on table, is leaning forward. Hideous, bald-headed, bearded, an old Jew sits crouched on the end of the divan; he seems to try to read le Soir. In the whole thing there is fine irony; and, as in another picture where a naked woman lies abandoned on a bed like a coiled snake, here also is sheer mastery of genius.

It is certainly strange that Forain should, in the midst of his usual work, have devoted himself to doing etchings on religious subjects: yet, to me, one or two of these might be compared—at whatever distance—with those done by the greatest masters. Take, for instance, not only Le Calvaire (1902), so utterly perfect in execution that, even in its poignant modernity, it brings before one's vision the actual Golgotha, but Le Retour de l'Enfant prodigue, in which I find an almost unspeakable sense of rapture in the passionate tenacity of the embrace of father and son; they have rushed into each other's arms, as the heat of the noon bears witness. This, indeed, might almost be compared with a Rembrandt, who has been wrongly accused of sensationalism in his use of light, of sacrificing truth to effect. At times he seems to do so, but he cannot distribute his light with the indifference of the painter to whom all visible things are equally important. He takes sides with people and things (does not Forain also?) loves and hates them (does not also Forain), and light is his touchstone, it draws and dissolves, ' Creates and criticises.

Perhaps it were better, on the whole, .to compare Forain with Rubens. Forain's creations are never evoked by tenderness; nor are they ever made to look beautiful because they have inherited beauty by right of birth. Where he is most like Rubens is in his content with . the appearance and mere energy of life; and, if anything, more content than Rubens, in the joy of merely being and moving which captures the senses. But, his taste for flesh being simply Parisian, he never attains for an instant Rubens' inexhaustible hunger and thirst for the flesh. To Forain, to most of his curious creations, satiety is almost everything: to Rubens satiety is unknown.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now