Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe New Plays

As Offered by Sera Benelli, Chester Fernald, Rachel Crothers, et al

DOROTHY PARKER

WITHOUT wishing to infringe in any way on the Pollyanna copyright, there are times when one must say a few kind words for the general scheme of things. After all, the plan really has been worked out rather cleverly. When everything has gone completely bad and suicide seems the one way out, then something good happens, and life is again worth the cost of living. When things have sunk to their lowest depths, some really desirable event occurs, and business goes on again as usual. When clouds are thickest, the sun is due to come out strong in a little while. In fact, the darkest hour is just before the dawn. (No originality is claimed for that last one; it is just brought in for the heart interest and popular appeal.)

The Pollyanna system has recently been worked out with particularly brilliant effect, in the theatre. When the latest attractions at the local playhouses were so consistently poisonous that one had just about decided to give up the whole thing and stay at home in the evenings to see if there was anything in family life—then along came Mr. Arthur Hopkins and produced "The Jest." And, once again, all's well with the world.

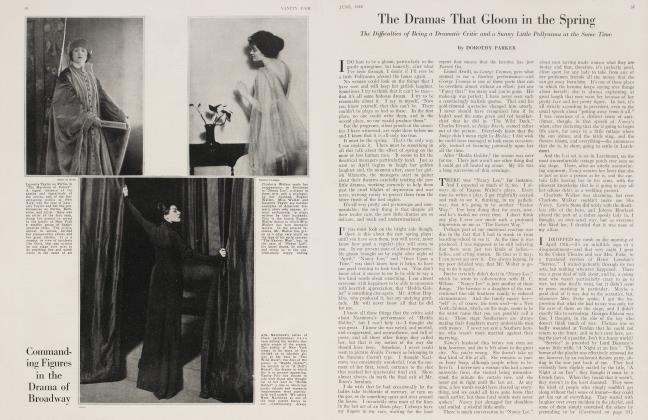

IT is difficult to write of "The Jest," for enough has been written about the thing to fill the Public Library comfortably, by this time. Everyone knows that it was written ten years ago by Sem Benelli—then in his late twenties— who was known in these parts heretofore only for his libretto of "L'Amore dei Tre Rei"; that in Italy, where its name is "La Cena Delle Beffe," it is practically a national institution; that Bernhardt played John Barrymore's part in French and another woman, Mimi Aguglia, played it in Italian; and that the present production at the Plymouth Theatre is the first English version of the play.

The name of the translator is no longer withheld; everyone knows that Edward Sheldon did the deed. Whether or not he has translated it into verse is still the subject of hot debates among the cultured. The ayes seem to have it, so far. If the English version is in what, in our youth, we used to speak of affectionately as dear old iambic pentameter, the actors mercifully abstain from reciting it that way; they speak their lines as good, hardy prose.

The Sunday supplements have printed long excerpts from the text, illustrated with scenes from the play and with weirdly blurred portraits of the author—portraits which look strangely like composite photographs of Harry Houdini and Josef Hofmann. The name Benelli has rapidly become a household word; little children in Greenwich Village chant it at their play, mothers hum it about the house; fathers whisper it through the smoke of their cigars. It is a good name for household pronunciation, too; you can't get into any arguments about it, the way you did about Ibanez.

IT is even more difficult to write about the production and the acting of "The Jest"— superlatives are tiresome reading. The highest praise is the attitude of the audience, every evening. They say—they've been saying it for years—that it is impossible to hold an audience after eleven o'clock. The final curtain falls on "The Jest" at a quarter to twelve; until that time not a coat is struggled into, not a hat is groped for, not a suburbanite wedges himself out of his mid-row seat and rushes out into the night, to catch the 11:26. One wonders, by the way, how the commuters manage; they must just bring along a tube of toothpaste and a clean collar, and make a night of it. Anyway, there is not so much as a rustle before the curtain drops. Every member of the audience is still in his seat, clamoring for more at the end of the last act.

There can be no greater tribute.

Once again the Barrymore brothers have shown what they can do when they try. They have easily outclassed all comers in this season's histrionic marathon—they have even broken their own records in "Redemption" and "The Copperhead." Their roles—John plays Giannetto, the sensitive young artist, and Lionel, Neri, the great, swashbuckling mercenary—afford a brilliantly effective study in contrasts. The part of Giannetto, exquisitely portrayed no less by gesture and pose than by voice, is in its morbid ecstasies, its impotent strivings, its subtle shadings, undoubtedly far more difficult than the blustering role of Neri. Yet the physical strain of Lionel Barrymore's performance must in itself be enormous. How his voice can bear up all evening under Neri's hoarse roars of rage and reverberating bellows of geniality is one of the great wonders of the age. Not an extraordinarily big man in reality, he seems tremendous as he swaggers about the stage; in his fight scene, he goes through a mass formation of supernumeraries much as Elmer Oliphant used to go through the Navy line. And in some strange way, he manages to make the character almost likable.

Again, one must present it to the Barrymores; they are, indubitably, quelque family.

IT is a bit rough on the other actors in "The Jest," for the Barrymores' acting makes one forget all about the other people concerned. It is all the more credit to Gilda Varesi that she can make her brief characterization stand out so vigorously. Maude Hanaford and E. J. Ballantine also contribute effective performances. But the Big Four of the occasion are unquestionably the Barrymore brothers, Arthur Hopkins, and Robert Edmond Jones.

Scenically, the production of "The Jest" reaches the high water mark of the season—which isn't putting it nearly strongly enough, unfortunately. Mr. Jones has devised a series of settings which are the most remarkable of his career; the year holds no more impressive picture than that of Giannetto's entrance, as he stands, cloaked in gleaming white, against a deep blue background, the dark figure of his hunchback servitor crouching at his side. The whole production is a succession of unforgettable pictures.

That, indeed, is just the quarrel that some people have with it. Those who have seen "La Cena Delle Beffe" on its home field say that the American, production is a bit over-spectacular—that the production cuts in on the drama. The attention of the audience, they say, is diverted from the action by the amazing picturesqueness of the scenes. Well, their view is high over the heads of the untraveled. To one who has seen only this production, any better seems impossible. The simple, homely advice of one who has never been outside of these broadly advertised United States is only this: park the children somewhere, catch the first city-bound train, and go to the Plymouth Theatre, if you have to trade in the baby's Thrift Stamps to buy the tickets. The play will undoubtedly run from now on. You ought to be able to get nice, comfortable standing-rooms, any time after Labor Day.

AFTER "The Jest," there is very little to talk about. As a matter of fact, there is not very much left in the theatres to mention. The latest plays have flashed on and off with a cinematographic rapidity. It took, as you might say, two people to tell about the New York run of Zoe Akins' "Papa." One said, "I hear 'Papa' opened last night," and the other remarked, "I see 'Papa' closed to-day."

(Continued on page 100)

(Continued, from page 41)

"Three for Diana," Chester Bailey Femald's comedy at the Bijou, bore the mark of the doomed, even on its first night. And that's too bad, for it had two decidedly pleasant things about it— Martha Hedman and John Halliday. It was such a poor, thin little idea to be stretched out into four long acts; it couldn't stand the strain, and snapped miserably, in the middle.

"A Good Bad Woman," a drama by William Anthony McGuire, opened at the Harris with a cast including Margaret Illington, Robert Edeson, and Wilton Lackaye. It was one of the most serious, not to say fatal, cases of the obstetrical school of drama. The only thing one can say about it is that the author undoubtedly wrote it in all sincerity and seriousness; otherwise it could never have had such a perfectly preposterous ending. Yes, there is, too, something else good to say of it; it had a charming setting. It seemed too bad that such tedious things had to go on in those delightful surroundings.

The actors had little opportunity to do anything to help it along, although Mr. Lackaye did his utmost to hold the public interest by wearing a trick moustache, half of which drooped dangerously throughout the play. For some mysterious reason, "A Good Bad Woman" is still in this world, at the time of writing. It must be supported entirely by the boarding-school patronage. All the sweet innocents, who send for those books in plain wrappers, will sneak away from their mothers' sides, to attend matinees. I, too, can remember those roseate days of happy girlhood when we used to skulk off to attend like dramas, thinking that we were seeing life. Ah, youth, youth. . . .

AT the Broadhurst is being produced Miss Rachel Crothers' latest addition to the treasures of the drama, "39 East." Before going any farther, one must say that it is a great success. Now let's go ahead and talk about it.

Miss Crothers knows her public well, she knows that the play which is founded on the pretty theory that no good woman can get along in this wicked world, is the play which buys the tires for your little Rolls-Royce. Many people say that "39 East" is such a sweet, .clean, moral play. Oh, very well—if you think that it's a moral play because it preaches the great lesson that no decent woman can support herself, why, go ahead. A sweet play it undoubtedly is—just too sweet and dear for anything. But one can't help feeling a little hurt about Miss Crothers. In the first place, she doesn't mean what she says. And in the second place, she doesn't say it in a new way. She has worked in all the old ones—the brusque landlady with the heart of gold; the inevitable boarding-house characters; the sweet little heroine, alone in a great city, who can't pay her board bill and is about to be dispossessed, but who wears a diamond wrist-watch right through the play. The authoress has written her play too flagrantly from the box-office viewpoint; she might have covered up her intentions a little more adroitly. It does seem a bit underhanded to strive for a laugh by naming her hero "Napoleon"; after all, almost anybody can do that. And, of course, the fact that it does get a laugh is what makes it so depressing.

Henry Hull and Constance Binney are delightful in their respective parts; it is they who save the syrupy play from crystallizing completely. And Alison Skipworth brings her usual crisp cleverness to the character of the landlady. There is also a property swan in the Central Park scene, who adds a refreshing note of realism.

But then—you will remember that it has already been' mentioned—"39 East" is simply turning 'em away.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now