Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMrs. Fiske—Still an Idol on Our Stage

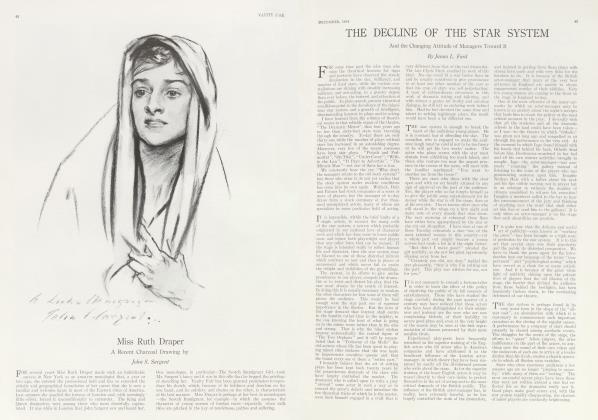

And the Chief Reason for Her Long Continued Popularity

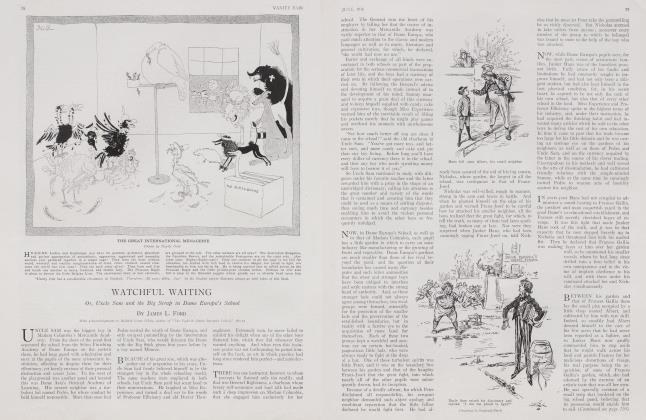

JAMES L. FORD

A FEW nights ago I saw "Mis' Nelly of N'Orleans," a comedy which was, literally, carried on the shoulders of an actress so successful, so distinguished and so widely known and honored that it is not an ungracious task to count the years that she has spent in the service of the American public.

So, even with the knowledge in mind of our American proneness to idealize immature youth and to snear at ripened theatric art, I feel that I am paying a tribute to Mrs. Fiske when I relate that as I watched her delightful performance the other night, my memory carried me back to another night, thirty-seven years ago, when from my seat in the Park Theatre I saw her as Minnie Maddem take the first important step in her career.

Of honored theatrical lineage, Mrs. Fiske's early years were spent in learning how to act, and it was no unfledged amateur who came skipping down the stage that night so long ago, in short skirts and poke bonnet, to be greeted by the applause of an audience made up largely of friendly professionals.

I AM speaking quite truthfully when I say that I went home that night confident that I had assisted at the debut of a young woman destined, by the Fates, for a long and distinguished career on our stage. And the same promptings of truth compel me to add that my judgment was not bom of experience and knowledge, but was merely the effervescence of youth easily deceived by the cordial plaudits, and that, in my narrow vision, Minnie Maddem was to continue skipping along the road to fame dressed in short skirts and a poke sunbonnet, much as if she had been a younger and nimbler Lotta. And I am quite sure that not one of that welcoming host could have foreseen another night, fifteen years later, when, in Hardy's "Tess of the D'Urbervilles," MinnieMaddern Fiske came, artistically, into her own and, in a single performance, established herself on the American stage as an emotional actress of rare and compelling power. But she did much more than that, for, in surrounding herself with a company of skilled players she struck the keynote of the generous policy that she has consistently followed ever since—a policy that has contributed very largely to her success and set her apart from the great majority of her rivals and contemporaries.

It should be remembered that Mrs. Fiske's novitiate was served at a time when the star system was at its worst and when our native playwrights were little more than dramatic tailors, called in to "fit" a player with a vehicle for the display of the many tricks and mannerisms that it is customary to group under the heading of what is still called "personality."

The custom of this cutter and fitter depended on his skill in providing the star with plenty of good things for her to say and do and on preventing the other actors from amusing or otherwise pleasing the audience.

Even such great players as Booth and Jefferson paid but small heed to their supporting companies; and it was not until Henry Irving's magnificent productions raised the whole standard of dramatic representation in this country that the public began to demand a competent ensemble—such as Mrs. Fiske has always tried to give them.

IT would amaze them to learn that the weeks of rehearsal, which should have been spent in making the entire representation as nearly perfect as possible, have been devoted to the idiotic work of imparting to it all the dullness that stellar ingenuity and vanity can suggest; that the ingenue has been taught to play the scenes in which she appears with the star, with her back to the audience; that the comedian's role has been ruthlessly cut down for fear he will make the audience laugh; and that the star, after appropriating to herself all the good lines in the minor parts has not been ashamed to say to the company: "The public pays to see me; not you"

In no business save the difficult one of amusing the public is an employee reprimanded for trying to earn his wage. No merchant was ever known to discharge a salesman for selling too many goods or to promote another for falling asleep behind the stove!

It is claimed by persons not over wise in the precise meaning of words that our stage is too "commercial." The trouble with it is that it is not commercial enough to understand the importance of giving the public full value for its money.

It is not" my purpose to discuss here either the "personality," the "technique," the "mannerisms" or the "limitations" that have made the art of Mrs. Fiske a fecund and engrossing topic for owlish reviewers of limited vision. I prefer to treat of another quality, but vaguely comprehended by the play-going public, though it is well known to every member of the dramatic profession—a quality that, more than all the rest, has made her after thirty-seven years of stardom, one of the most conspicuous and popular artists on the American stage. Of what other star can this be said?

I can name inferior players who have sought to filch some of her wellearned popularity by careful copying of her so-called "mannerisms," but not one of these simians has ever been known to copy the artistic conscience that compels Mrs. Fiske to consider a representation, in its entirety, as a means of public diversion, instead of a mere vehicle for her own vanity.

MANY a star employs players of recognized talents, and even, with assumed generosity, "features" them, by photograph and paragraph, but Mrs. Fiske not only pays them their salaries but encourages them always to improve their hold with the public.

Of the many plays in which Mrs. Fiske has appeared since she first tripped down to the footlights in her short skirts and sunbonnet, the one that made the deepest impression on me was "Leah Kleshna," with George Arliss, John Mason, Charles Cart-wright and William B. Mack in the supporting company. And each one of the four gave a finished and unforgettable performance. It was a cast calculated to dismay the average star, bred in the idiotic creed that no one in the company should be permitted to "take the stage away from her" or, in other words, to add to the interest of the drama. And yet, Mrs. Fiske shone all the more brilliantly in the title role because her efforts were seconded by so many accomplished artists.

And it is a matter of history that during the rehearsing of "Leah Kleshna" Mrs. Fiske voluntarily gave a "curtain" which had, of course, been written for her, to Mr. Mack, for the unheard of reason that the change would benefit the representation. I regard this episode as one of the most important landmarks in the development of our national drama.

To sum up my case in favor of the perfect ensemble which is Mrs. Fiske's constant aim, I would recommend budding stars whose privilege I trust it will be to play before audiences more critical and enlightened than those of today, to permit their consideration of a play, when it is offered to them, to go beyond the stellar part and to do their best to make the other parts as interesting as possible.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now