Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Earlier Work of Arthur B. Davies

Importance of His Group of Canvases Shown at the Recent Montross Sale

FREDERICK JAMES GREGG

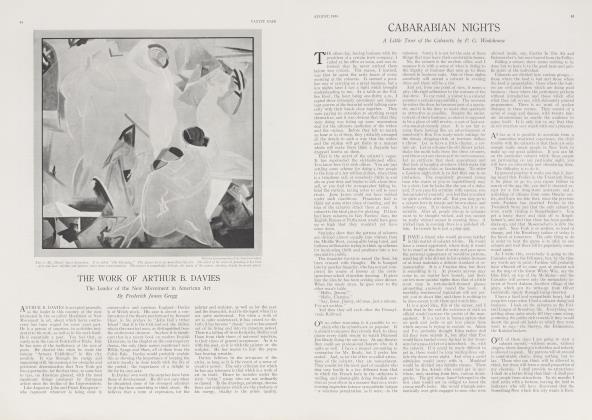

EIGHT early paintings by Arthur B. Davies, from the personal collection of N. E. Montross, appeared in the recent exhibition of canvases by American artists, in the American ArLGalleries. This in itself was an event. The public is familiar with this artist's recent work in the field of so-called modernist art.

A Davies retrospective show at the Macbeth Galleries, a few years ago, consisted of things that covered the painter's whole career. The small group just displayed was useful as supplementing that very large group, for the purpose of comparing only his early work with the more recent canvases which have brought him so much homage and fame.

As for the general reputation of Mr. Davies, at the present time, it is sufficient to say that it has passed far beyond the region of controversy. One of the most serious of New York's art guides remarked some time since, with a characteristic combination of enthusiasm and caution; "Davies can paint like the angels." As there never has been an exhibition of the works of the choir invisible, it is hard to say exactly what this means, but, were a comparison between them and Mr. Davies at all possible, our own judgment would, we feel, be certainly in favor of Mr. Davies.

It is altogether too bad that the critics should be disturbed about this painter's new manner at the very moment when they have grown accustomed to what they could not "see" in his work, say, as back in the nineties. This is one, among a number of reasons, why artists, like those whom the gods love, ought to die young. If they followed this rational and reasonable course there would be no chance of their upsetting the critics' neat system of classification, according to which every painter has his place which he ought to be made to keep, from the time when he first shows that he is worth any attention at all.

NO artist is to be blamed because others have pinned labels on him, or even because he has pinned one on himself. Mr. Davies has been called a "symbolist", a "mystic" and even an "imagist". The favorite definition, in his case, however, is "romanticist". This may mean that he is supposed to be influenced by what is extravagant; to be sentimental rather than rational ; that he is affected by what is strange or fantastic; that he is opposed to classicism, or that he is "poetic". All this is purely arbitrary. There might be a sense in which some of these things might be said of Mr. Davies, yet the definition, in any of its senses, really gives us very little assistance. Mr. Davies is a poet. This statement is not a novel one. But it is important. The fact explains why there is a tendency to read into his work signs—and somewhat fatuous—explanations, like those which delight the souls of concert goers, in the case of what is known as programme-music. There seem to be a host of well-meaning art critics in the world who like to ask learned questions, much in the manner of the Scot, who, after reading "Paradise Lost", asked "What does it all prove?" No artist who ever lived had less desire to demonstrate anything, logical or spiritual, than Arthur B. Davies.

It is true that there is a great deal of the passion of life in the work of this painter. He has a keen sense of essentials. Besides, he has an almost uncanny gift for creating a sort of reaction between his figures and their surroundings, which starts those who are imaginative about the obvious, on the track of all sorts of hidden meanings which are not there.

LET us consider the group of early canvases shown in this sale. Take "The Searcher", a figure in an autumn landscape, for instance. It must have been disturbing to Mr. Davies to be told, by critics and students, that the woman, with her hand to her ear, was intent on finding out the source of some secret song. This was merely reducing a very lovely thing to the level of a story-telling picture. Here indeed the painter is at fault. By his title, quite unnecessary at it is, he has ppened the door to the most trivial speculations. Indeed, who cares what the lady is interested in? The painting is the thing, and the painting is perfectly satisfactory from every point of view.

(Continued on page 98)

(Continued from page 55)

In the same way it is not worth while to speculate on a certain side of the "appeal" of the lovely "Call of Spring". The nude figure of the girl may or may not suggest the vegetable emotions of the two silver birch trees, just as the trees and the earth may or may not "symbolize" the sensations experienced by the young woman. It is much more satisfactory and profitable, not to philosophise about invisible emotions and inaudible sights and all that sort of thing, and just to realize that the naked figure is essential to the design; that the tree trunks are simply part of a fine composition.

(Continued on page 100)

(Continued from page 98)

In "Reluctant Youth", the artist has just painted the portrait of a girl, with a background that is almost early Dutch in its realism. There is a plain house with a balcony, on which is a figure. A rough road winds round the slope below the building. On this thoroughfare is a very old-fashioned buggy. There is a delightful suggestion of summer, but summer made to serve the need of a painter.

Strange meanings have been read into "A Greater Morning". Some have found in it the suggestion of the presence of a new Eve, a new Adam and a new world. In the foreground is the reclining figure of a mature nude woman. At the edge of the water, which stretches to the horizon, a naked man is busy, probably with a boat. Two great headlands are in the left side of the composition. The water, the sky and the cliffs glow with a vivid light. It is only necessary to see this picture to come to the conclusion that Mr. Davies is not only a great landscape painter, with a splendid sense of design, but a great poet as well.

THERE is nothing that he has done in later years that is not to be found, in some form, in this fine group of early pictures. Though in some of his more elaborate decorations—as in those in a well known New York room —very "modernist" experimentation is added to, or rather superimposed on his earlier manner, there has never been an artist less capable than he of escaping from his own personality, a personality which makes itself felt in whatever he produces, in half a dozen mediums, from oils to etchings and wood-carvings.

It may be said of Davies, that there is no living American painter about whom there is so much curiosity. If he shows himself seldom, and with reluctance, it is certainly not for the purpose of stimulating this feeling among the vulgar. While he has no use for official art, and believes, with the late Herbert Spencer, that whatever a man

accomplishes in a great way, must be done by him as a solitary, he is always willing and eager to believe that things are possible, which experience has demonstrated, time and again to be impossible. Hence his great belief in the talents and powers of the very young man.

Since the death of Albert P. Ryder, Mr. Davies has been recognized, by persons abroad who are familiar with art in America, as the leading living painter on this side of the Atlantic. One of his works, shown at an exhibition at Venice, many years ago, was adjudged the best canvas in the show. It will be interesting to see to what extent he will be represented in the collection of paintings and sculptures to be sent from this country to Paris in the near future, for the purpose of bringing about a closer relationship between the artists of France and the United States.

At any rate, it is reasonable to predict that when the time comes for a representative collection of Mr. Davies' work to be shown in London, Paris and Rome, the recent remark of a visiting foreigner of note, "Why is it that America does not produce great painters?" will be a good thing to recall for the benefit of the questioner, and of all critics overseas.

The Montross sale proved to be conspicuous by the absence of private collectors to whom the works of Albert P. Ryder, John H. Twachtman and Arthur B. Davies appeal. Perhaps they were not there because they are suffering from the depression induced by the present riot of Federal taxation. At any rate, some of the top prices were fetched by academic canvases which are likely to prove most marketable, just now, when a new and inexperienced crowd of prosperous persons are out to make themselves respectable by buying "Art". As the man said who 'picked up a little Manet and a Degas at a Paris sale, much to his subsequent advantage, "it was a great day if you had your wits about you".

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now