Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent, Not to Say Incurable, Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

ALMOST every convention recently introduced to the game of auction is in the nature of a bye product, using up some part of the game that has been discarded earlier in its history. As soon as it was found that it did not pay to double a bid of one to get penalties, that declaration was out of a job. It is now working overtime as a convention, for both suits and no-trumpers.

Another bid that has been for some time abandoned as .superfluous, is the original call of two in a minor suit. It was formerly used as an invitation to the partner to go no-trumps, but experience proved that he would make that declaration just as readily on a bid of one, if he had the cards to do it with.

Borrowing the idea from the game of pirate, many players are now using this two-trick bid in clubs or diamonds as a convention to make soundings for the safety of a no-trumper. Here is an example of its use and the defence to it.

Z deals. The usual bid upon his cards would be no trump; but in order to avoid the risk of finding all the diamonds against him he bids two diamonds. This is the logical extension of the conventional suit double, and conveys to the partner the same command to bid something.

If we suppose the player on Z's right had dealt and bid a diamond, Z would have doubled. This commands Y to go no-trumps if he can stop the diamonds twice, or to pick out his longest suit. As Z has no diamond bid ahead of him which he can utilize by doubling, he practically does both the bidding and the doubling himself by bidding two diamonds.

The defence to this convention is for the adversary on the left to double two diamonds, so as to show where the tops in diamonds really are. If A fails to take advantage of the opportunity to do this before Y bids two spades, B will probably pass, and play to save the game, allowing Y to make three by cards and 36 honors.

The double by A does not affect Y, who calls two spades; but B, advised as to the true position of the diamonds by A's double, goes to two no-trumps. Z assists the spades, bidding three, and B goes to three no-trumps. It would have paid Y or Z to go on to four spades, and be set, but in the actual game they did not do so.

B made his contract by holding off two rounds of clubs and then running down six diamonds and finessing the heart jack.

In a future article VANITY FAIR will have something to say about the use of this convention in forcing a suit bid from the partner, and avoiding a no-trumper.

A VERY clever player from the Racquet Club in Philadelphia was recently invited for a week end at Newport, where he found many new and interesting varieties of auction in vogue, interspersed with every crime known to the lovers of bonehead bridge.

After the first evening's play he formulated the following rules as an addition to his previously acquired maxims on bidding and play.

1. Underbid your hand sufficiently to stand two raises from a partner who has nothing.

2. Do not assist unless you have two tricks more than would be required at the Racquet Club.

3. Play the hand yourself at the loss of a trick, as your partner would probably drop at least two.

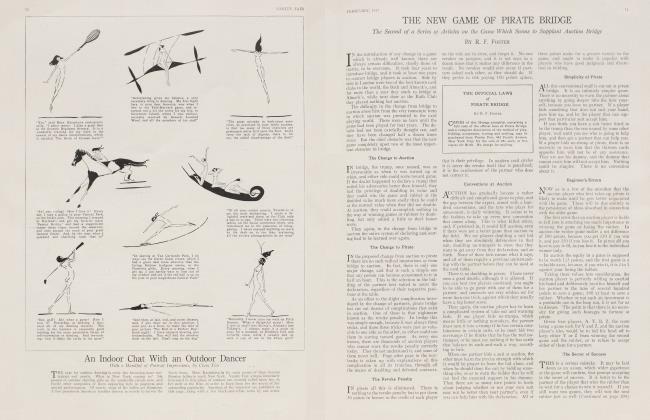

Cutting into a table the second evening, he was agreeably astonished at finding himself the winner of 2,300 points in three rubbers, the result being chiefly due to the energetic and optimistic bidding of the lady on his left, a Mrs. Gethair, from Chicago, one of whose peculiarities was to regard it as a personal insult if her partner took her out, or an adversary overcalled her more than once. To his dismay he cut her for a partner the fourth rubber, and this was the distribution the first time Mrs. Gethair dealt.

The Racquet Club Player

Mrs. Gethair's hand

"I make it hearts," was the prompt announcement, before her cards were half sorted. After due deliberation, the second player, naturally timid, and apparently overawed by the breezy bidder from the West, ventured to say one spade.

Applying his new set of rules, the Racquet Club player passed. So did the fourth hand, but Mrs. Gethair unhesitatingly announced, "Two hearts," with a glance of defiance at her left hand adversary, who shrank into himself as if he had been guilty of some crime in even mentioning the spade suit. His partner, however, was not so easily cowed, and wished to encourage him to continue the bidding. With that laudable end in view, instead of assisting the spades, she doubled the two heart bid.

The Racquet Club player immediately brought into request all he knew about mental telepathy to prevent his partner from redoubling, or going to three hearts, which he had observed was her usual way out of a double. When she passed, he exercised the same spell on the timid player to his right, hoping to drive him to two spades, but without success. He could have set the spade contract for two tricks.

The declaration coming up to him, he seriously considered the advisability of applying his third rule, and bidding three clubs, so as to get the play of the hand, but the double on his left deterred him. Had he taken the chance and been doubled, he would have been set for about five hundred.

Answer to the July Problem

In our last issue we presented the following interesting little ending from actual play, when only seven cards were left in each hand:

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks against any defence. How do they get them?

HERE IS THE ANSWER

Z leads a club which Y trumps. Y leads the jack of trumps, on which Z discards the king of spades. Y leads a diamond and Z makes two tricks in that suit. Then Z leads the spade four.

Problem V

Here is an instructive little seven-card ending, the solution of which will be given in the September Vanity Fair:

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want all seven tricks. How do they get them ?

(Continued on page 78)

(Continued from page 55)

The first card played was the king of spades. When the dummy went down Mrs. Gethair gasped with astonishment and inquired with some hauteur if that was not considered an assisting hand in Philadelphia, at the same time playing from her own hand before she played from dummy. This trick of playing from both hands without waiting for the intervening opponent was supposed to save time, and if the result was not satisfactory, the card was put back and another substituted, the opponents being too polite to protest.

Two more spade leads followed, the third being trumped. The next lead was the four of diamonds, to which Mrs. Gethair played the ace from dummy before putting on the trey from her own hand, as she was in a hurry to lead trumps. The trump lead was promptly stopped by the king and two diamond tricks had to be surrendered, after which the ace of trumps set the contract for 200 points, less simple honors.

"Very unfortunate, partner," remarked the fair player from Chicago, as she cut the cards for the next deal, "but, of course, you had nothing in spades to help me. I had six trumps and a singleton. A perfectly wonderful hand."

The Racquet Club player found all his good manners necessary to prevent him from remarking that if the ten of diamonds had been played second hand it would have killed the queen and saved a trick, and if dummy had led the clubs, instead of rushing to trumps, they would have made their contract, which, at double value meant the game.

Before retiring for the night he added a fourth maxim to his repertoire, "If your partner is in the habit of playing without waiting for the opponents, add a trick to each of the previously stated allowances."

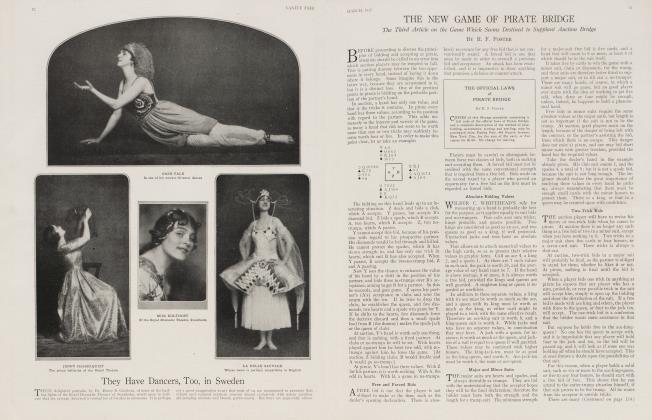

W. C. Whiteheads Ideas About Auction

It is generally admitted that in the matter of play there is little to choose between the top notchers in any of the first-class clubs, and that any great disparities in results can usually be traced to the bidding that precedes the play of the hand.

Any system of bidding which can enable a team of four players to pile up an average of 65 points a deal for 60 consecutive deals at duplicate auction, when pitted against the best players from New York, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Hartford, and Scranton, playing for the championship of the United States, must be well worth considering.

The system used by the winners, the Knickerbocker Whist Club of New York, was first enunciated by Wilbur C. Whitehead, the captain of the team, whose picture appears in this issue of Vanity Fair: "Every hand has a fixed mathematical value, which can be ascertained and acted upon." In an interview, he was good enough to give readers of Vanity Fair an outline of his ideas with regard to the modern game of auction.

"I find the greatest obstacle to any material improvement in the game of auction as generally played, is not so much the fact that the generality of players know absolutely nothing about the elementary mathematical principles governing the bidding and the play, as it is the fact that they are quite content to know nothing; and that they usually resent anything in the shape of advice or criticism, no matter how well intended, or how great the need.

"Arthur Brisbane, in one of his editorials, says: 'Curious is the inborn human dislike for anyone that possesses, or seems to possess, superior knowledge. Everybody remembers the lady living in the slums who resented the offer of advice from a trained nurse about the care of children: "You would tell me how to care for children?" retorted the indignant mother, "me that has buried seven." '

"Auction is a mathematical game. The factors that determine what is a justifiable bid or play are mathematical factors. No bid or play in auction is justifiable that will not average to win more often, or at least as often, as it will to lose. The factor of personal equation has no bearing whatsoever upon what is, or is not, under normal conditions, a justifiable bid or play. Therefore, unless players know at least something about the basic, or elementary mathematical principles, they are not qualified to formulate any theory, or to express any opinion, as to how auction should be bid or played.

"Confronted by the fact that the fifty-two cards used in the game can be distributed among the four players in more than six hundred and thirtyfive billion different ways, and that if one player holds thirteen cards in any of these distributions, the remaining thirty-nine can be distributed in nearly nine billion different ways against him, it should be obvious that individual opinion in auction counts for nothing, unless such an opinion is based upon the immutable law of averages, as applied to card values and card probabilities.

"In making this statement it is not my idea to discourage auction players by making the game appear difficult. Far from it. Thoroughly to enjoy auction it is not absolutely necessary to know how to play it well. I sometimes think the duffer's enjoyment of* the game may be even keener than the expert's; always provided that the duffer plays with those whose knowledge of the game is on a par with his own.

"What is desirable is to awaken players to the fact that in order to compete against experts with any hope of success, or to qualify as acceptable partners or opponents in expert circles, one must possess a thorough knowledge of card values and card probabilities; otherwise they can never hope to win, or even to hold their own, against expert players, unless they hold overwhelming cards.

"While statistics are usually dry reading, it may interest the average player to know that the margin in favor of superior knowledge of auction bidding and play is at least twenty per cent when pitted against those whose knowledge is slightly inferior, and it may be as high as forty per cent against players of marked inferiority. Two of the strongest players at the Knickerbocker, Leibenderfer and Lenz, consider these figures too low, while E. V. Shepard, the author of 'Expert Auction,' considers them approximately correct. My figures are based largely on the individual and team scores made in the play for the championship at Spring Lake, which showed a gain of 3,785 points in trick and honor scores, above average, in 60 deals. This result was directly due to mathematical bidding and play.

"Materially to improve one's game of auction, one must at all times be willing to learn; to accept, instead of resenting, the advice or friendly criticism of better informed players, or of persons who have learned something about the value of a hand, or of one who has perhaps stumbled upon some fundamental truth, hitherto unknown. After all is said and done, what anyone actually knows, or ever will know, about auction, marks an infinitesimal degree on the vast scale of possible knowledge."

(Continued on page 80)

(Continued from page 78)

Hard Luck Hands

It is a curious trait of human nature that we are usually amused at the misfortunes of others, and that in. the game of auction any piece of unmitigated hard luck is greeted with a laugh; the only commiseration coming from the partner, probably because he has to pay.

Here is a specimen of the hard luck article, unadulterated. A player with eight spades, backed up with an ace, king, and a queen in other suits, is doubled and set for 300, although he found only three trumps in one hand against him. This was the distribution:

Z dealt and bid a club, A a diamond, and Y two spades. B went to three diamonds, Z and A passing. Y said three spades, which B doubled, and that ended the bidding.

B led to his partner's diamonds and Y won with the ace. By leading the king of clubs, and overtaking it with the ace in dummy, Y plans to get at least two heart discards, while dummy can still ruff the diamonds. But A trumped the club, so that Y lost four tricks in trumps, two hearts' and a diamond. An immediate lead of trumps would have saved two tricks, which is all that the discards would have done, had A held three clubs. It is a game hand in diamonds for A and B.

Here is another, even more promising, still more disappointing:

Z dealt and bid three hearts. This did not stop B from calling three spades. Z went to four hearts and when A went to four spades Z thought he could risk being set 100 to save the game, and bid five hearts. This A doubled. Y, attaching undue importance to his five trumps, and failing to ask himself what he was going to do with them, redoubled.

A led his partner's suit, spades, and after making both ace and king, B laid down his singleton club. Then he led a diamond, which A won with the ace, returning a club, which B trumped. B then took a chance on the third round of spades, and A made the king of trumps.

The contract to win eleven tricks with hearts for trumps, on which Z calculated to be set 100 at the most, with an honor score of 72 to offset the loss, went down for 800.

The only consolation offered by his opponents was that they would have made four spades easily, if left to play the hand on that contract.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now