Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTen Great Names of the War

Although Others Will Be Added, These Will Never Be Forgotten

FREDERICK JAMES GREGG

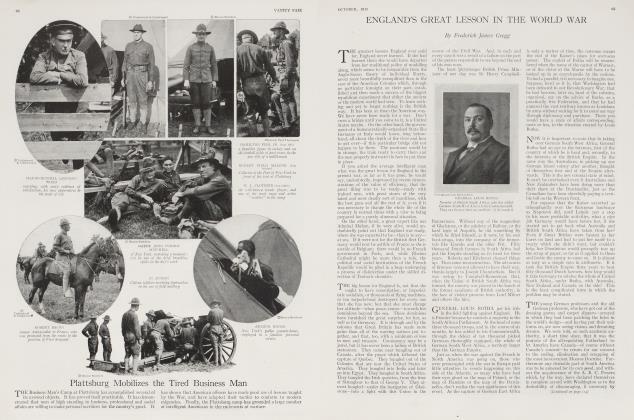

THE war has lasted long enough to give Time the opportunity to take toll of many reputations. Figure after figure has held the stage and then disappeared into the wings to be seen no more. The danger of making any tentative list of those who will be known to history as the principal actors lies in the fact that sooner or later, a brilliant victory, at sea or on land, may upset all speculations by supplying the Allies with a Grant or a Nelson, in the person of a Pershing or a Beatty,—an individual who will have the sort of fame about which there can be no doubt or dispute. But, all the same, certain reputations seem to be safe in advance, in spite of the ever-present d'anger of prophecy.

FIRST, the Kaiser. Nobody could be so absurd as to deny him the right to his bad eminence. He started the blaze that ran round the world, literally from China to Peru. Like Satan in "Paradise Lost" he dominates the epic. His was the hand that set armies of millions in motion. Failure Lo become World Lord, like a similar failure on the part of Louis XIV, and then on the part of Napoleon, won't work to prevent this terrific and heroic period from being known as his.

When, at some date in the dim and distant future Germany has paid off the last mark that she owes, the memory of her agony Will be as fresh as ever. Every schoolboy will know how William II reversed the plan of the Corsican. For, whereas Bonaparte began by saving France and then wanted to dominate, humanity, the German Emperor started out to conquer the earth, and then pled that he was only trying, from the first, to save his people from their enemies. There is only one proof that he did not foresee the war, and that is his bestowal on his grandfather, William I, of the title "the Great," in order to belittle, by contrast, the reputation of his own father, whom, as a gallant gentleman and soldier, he could never understand. Had William II thought of riding in triumph through Paris, London and New York, to him would have been given the title of "William the Great," instead of to William I.

SECOND, Lloyd George. In spite of Parliamentary intrigue he succeeded in industrially making over Great Britain. Those who honor him with the designation of "little Welsh attorney" only emphasize the fact that one without the "advantages" of birth, or at least of school and university, supposed, to be necessary in the case of an English Premier, should have had the courage to drive a coach and four through the sacred prejudices of Britons on the subject of government.

"It isn't done, and it can't be done," wailed members of both Houses of Parliament. "But I'm going to do it," answered the awful radical, and he did. When he revised; over night, and without as much as saying "by your leave", the whole cabinet system, not only did the Empire back him up, but the French immediately followed his example. He will be remembered, among other things, as the man who was, for a time at least, practically the Prime Minister of most of the Allies, since he had to decide on ways and means for those who had the men, but not the money.

THIRD, Kerensky. He will be remembered as a symbol of the Russian Revolution. Ten years ago he was a prisoner in Siberia, sent there because he was too free with his opinions. Now Nicholas Romanoff, head of the system that sent him, has been railroaded East to grow up with the country. When it was not the thing for lawyers who hoped to get on to appear for Jews, Kerensky defended them, with the same courage that he was to show, later on, in facing mutinous troops who: had been got at by the paid German agents who abounded in Petrograd.

As for the man's personality, enough is said when it is recalled that the Russian Premier. stirred the cold, unemotional mind of Elihuj Root to enthusiasm, when as Special Ambassador to Russia, Root met the man of the hour face to face, in the middle of the greatest crisis in the history of the country.

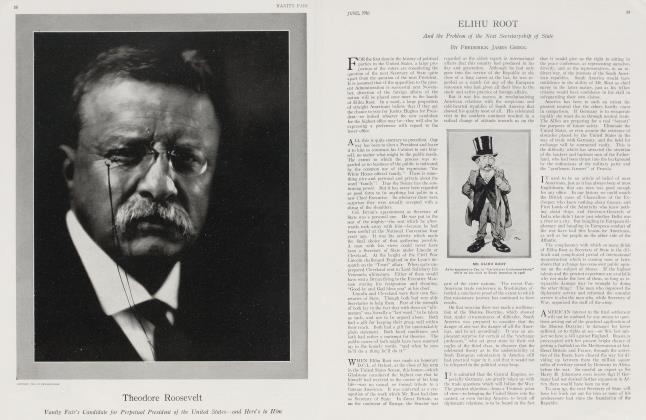

FOURTH, President Wilson. For two years he kept his temper under injuries and insults that would have shaken even the monumental serenity of Lincoln. It is admitted already that his second term ends one epoch and opens another in our history. Congress has been compelled to thrust upon him powers far greater than those exercised even by the man who saved the Union. Burdened by the most exacting of offices, he is yet, in reality his own Secretary of State. He has destroyed the myth, made in Germany, that the United States do not count in international affairs. When the Peace Conference comes, sooner or later, it will be for him to decide to what extent the theory of Washington on the subject of entangling foreign alliances will have to be modified, in order to enforce the decision of the court, and also because of the fact that America has been brought by modern ingenuity to within a few days' sail of Europe.

FIFTH, von Hindenburg. He is so necessary to the Fatherland that the Kaiser can't afford to be jealous of him. He offers in his own person a comfortable proof, to those who are getting along, that the axiom, "young men for action; old men for counsel", is far too sweeping. The action of his fellow countrymen in raising a wooden statute' of him and paying money to drive nails into it showed that they were not given over entirely to adoration of efficiency, but still had a little sentiment; left. Whether he carries his own brains, or allows his chief-of-staff, von Ludendorff, to take care of them, is one of the secrets of the war that the future alone will reveal. On this subject the Field Marshal maintains a masterly silence.

(Continued on page 126)

(Continued from page 43)

SIXTH, Joffre. He is the greatest defensive general that the war has produced. The saving of Paris, at the victory of the Marne, put him among the immortals. His conquest of America, when he came here, and the fact that he has placed his experience at the service of our commander in chief, General Pershing, have made him one of our national heroes. Not even the most timorous of Frenchmen, haunted by fears of a man on horseback, ever suspected him, even at the height of his popularity, of having any interests outside his profession. Joffre proved that France unready had more staying power iri her than had Germany after forty years of preparation.

SEVENTH, Kitchener. He was not only a prophet, but a worker of miracles. He horrified England and amused Germany by saying that it would be a three years' war at least, and turned Great Britain into a land power of the modern first class by raising an army of 5,000,000 men, whereas she was supposed to look out for things at sea, and send only an expeditionary force to the Continent. The theory that he had finished his work when he went to his death, is put forward by those who contend that he made mistakes—at Gallipoli for instance. Anyhow he raised the men, and in Sir William Robertson, chief of the Imperial Staff, developed a man big enough to wear his boots when he was gone. And what Robertson is to Kitchener, Pétain is to Joffre.

EIGHTH, Haig. He has lived down the reputation of looking well in any uniform. He has put push into what was once "French's contemptible little army''. Not only has he the Somme and the Aisne to his credit, but he has demonstrated that he can go through whenever it is desirable. He may prove to be the Wellington of the war. His despatches are as simple as if they were nothing but routine and commonplace descriptions of the day's work. He does not advertise.

NINTH, Cadorna. Alone of all the generals on both sides he has retained the supreme command ever since his nation got into the game. The victory of Monte Santo may rank with the Marne in the sense of being that rare thing, a decisive battle, opening as it did the way to Trieste.

TENTH, von Tirpitz. The father of the German navy will be best remembered as the adopted father of the submarine, an instrument through which the body of rules known as International Law were put out of operation for the first time since they were adopted. Frightfulness and von Tirpitz remain synonymous terms. But the doctrine of "thorough" was too much even for the Germans who balked at losing the last shred of reputation in pursuit of a policy which was to prove only comparatively successful.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now