Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE NEW GAME OF PIRATE BRIDGE

The Concluding Article on the Game Which Is Supplanting Auction

R. F. FOSTER

AS this is the concluding article on pirate bridge it should be interesting to note what the game has accomplished since it was first brought to the notice of the cardplaying world through the columns of Vanity Fair six months ago, and to glance at its probable future. Next month Vanity Fair will have something interesting to say about the latest wrinkles in straight auction.

While pirate bridge has undoubtedly made greater strides in popular favor in these six months than any other variety of bridge has made in three years, it is not to be assumed that the game is perfect. When pirate has had the time and attention that has been devoted to its forbears it will probably fall naturally into its place as the best card game in the world for players of widely varying abilities.

In the meantime, during the early stages of its career it has been deemed wise to keep it as close to the lines of auction as possible, in order that any person who is familiar with the older game shall not have to learn too many new things in taking up the new. The simpler the rules for a game, no matter how difficult it may be to play it really well, the more popular that game will become.

Progenitors of Pirate

COMPARED to the time that it has taken other members of the whist family to get acclimated and secure universal approval, the rise and progress of pirate is almost as remarkable as the career of Walter Travis.

Bridge was introduced to the whist-playing world in the spring of 1893, but there were no official rules for the game until four years later. Just ten years after The Whist Club published the official laws of bridge, July 20, 1907, to be exact, the first description of auction appeared in this country. Nothing more was heard of it for fifteen months, but on October 11, 1908, another description of the game appeared, differing materially from the first. So little interest was displayed that auction was not mentioned again for nearly two years, although the English clubs were all playing it.

At that time the arguments that were brought forward against auction, as compared to bridge, were precisely the same that are now urged against pirate as compared to auction. Every one said bridge was too good a game to be interfered with. The experts said that if all the players were allowed to name the trump best suited to their hands, the strongest hands would get the declaration and there would be nothing to it for the other side but to sit tight and take their medicine.

That this turned out to be largely true is evident from the fact that today two out of every four hands played go game from zero. Any one who is old enough to recall the advent of auction must recognize that the reasons for rejecting it and sticking to bridge have all turned out to be true, and are just what auction players are saying about pirate today. In spite of this, where is bridge now, and where will auction be tomorrow?

How Games Develop

ON October 23, 1910, the first schedule of what was then considered correct bidding for auction was published in the N. Y. Sun. On the 15th of December that year the first game of auction duplicate on record was played at the Lotos Club. Dalton's book came out in 1909, and "Badsworth" early in 1910. Three years after the game had been introduced in this country we find the following account of its progress:

"Although The N. Y. Bridge Whist Club has tried to arouse some interest in auction, giving lectures on the subject and inviting the members to try it, it has fallen dead. At The Whist Club, the committee, whose laws on bridge are the recognized authority throughout the country, do not consider auction a good club game, because of the length of the rubbers and the fact that a player is so much at the mercy of a poor partner."

While the present system of bidding in pirate is kept as closely as possible to the system in auction, there is no telling what changes time and experience may bring about. When the first duplicate game of auction was played in this country, we find the following instructions as to the bidding system:

"The more common system, because of its simplicity, is to make the first round of the bids upon trick-winning cards, irrespective of length in the suit. This with a view to leading up to the goal of all auction players, the notrumper.

"Should a player hold no high card in his hand but an ace, he should name that suit, bidding one trick in it. With both king and queen in any suit he should bid it, because he has a sure stopper on the second round at the furthest. This one-trick bid shows command of one suit if the partner has the others for a no-trumper, or tells him what to lead if the adversaries get the declaration."

Imagine a modem auction player bidding a heart on the ace and deuce, with no other card above a-nine! The theory of auction has undergone some radical revisions in the past six years, and pirate will probably undergo quite a number of changes from its present form before it is firmly established in popular favor. The game is young yet, but at the end of six months it has made more progress than either bridge or auction made in three years.

No card game, with the single exception of cribbage, has retained the form in which it was first introduced to the world. The larger the number of persons who take Up a game the greater the likelihood that it will be improved. The whist that was played. by the American Whist League in the 90's was a very different game from that of Hoyle, or Pole, or Cavendish. The poker that is played today would not be recognized by those who bet cotton bales and negroes on pat hands when there were only twenty cards in the pack.

Many persons still remember the difference of opinion among bridge players when one faction advocated the "heart and strong," while another stuck to "weak and weak." Some objected vigorously to the original spade, while others were dead against the fatal diamond. They were still arguing about conventions when auction swept them all from the field.

The Future of Pirate

AFTER sifting over all the criticisms, objections and suggestions that have come to hand with regard to pirate since these articles began in Vanity Fair, there seem to be only one or two that are entitled to serious consideration, and even these seem to be based on insufficient familiarity with the game. Just as when auction started, players are apt to form hasty opinions, which undergo many modifications as they see deeper into the fine points of the game.

One objection is that if the two strong hands get together there is nothing to the play, "almost every deal being a little slam or at least a game," as one critic puts it. But this is equally true of the strong hands at auction when they sit opposite each other and there is no opposition. It is not by any means true of "almost every deal," because there are so many cases in which the bidding is carried to high figures, and the contract is difficult to fulfil.

One objector points out that there are so many hands in which two players get the contract without any opposition and are able to win four or five by cards on hands that bid only one or two. The same is true to a much greater extent in auction, as the bids run smaller.

Bidding the Full Value

A REMEDY for this has been suggested by several good players, and it may perhaps become part of the game at some future time if it is found practical. This is to limit the scoring to the bidding. If the declarer gets the play on a bid of two accepted hearts, for instance, two by cards is all he can score, no matter how many he makes. If he has a game hand, strong enough to win four odd, he must bid four and get an acceptor. If he wants to score slams, he must bid them.

On hearing this explained, some persons will at once exclaim, "Oh, the same as five hundred!" But it is not the same by any means, because in five hundred the players have only one bid and each is for himself. One result of making such a rule at bridge would be that the hand might be thrown up the moment the contract was reached, which would materially shorten the time of a rubber.

This system of limiting the score to the bid has been tried at auction, but without much success. I tried it, and it seemed to increase the tendency of some players to overbid their hands for fear of missing something; while it led the cautious players to be even more cautious, with the result that it usually took four or five deals to win a game.

There are probably not a dozen players in the country today who could understanding^ bid their hands up to four odd every time they were good for game with a major suit. At pirate they could do it easily and to do it right along.

(Continued on page 81)

(Continued from page 61)

The best available statistics at auction show that 50% of all the hands played go game without any assistance from a previous score. But in 2,500 recorded deals only 280 bids were high enough to go game, and 146 of these failed. That means that in 2,500 deals only 134 bid enough to go game and made it. If the object were to go game from zero every deal the average rubber would be 47 deals, instead of 5, as at present, and the average time 7 hours.

The auction player tries to get his contract as cheaply as possible, and carefully avoids increasing a contract that looks in the least doubtful. The only occasions upon which he deliberately bids more than is safe is when he is afraid of an adverse declaration against him.

In pirate, one is never afraid to bid, because no harm is done if the bid is not accepted. If it is accepted, the contract should be safe. But if it were the rule in pirate that a player could not score more than he bid, he would have a great advantage over the auction player because he can show more by his bids. Having a chance among three players to choose his partner, instead of being confined to the one opposite him, there should be three times as many opportunities to bid game and make it.

Allowing Acceptor to Bid

BUT there is one rule which would have to be changed, and that is the law which prevents an acceptor from overcalling his own acceptance. This rule was made to prevent endless or useless bidding. But if it were essential to success that the combination of two hands should arrive not only at the best trump suit, but at the maximum value of the contract, there should be more room to show supporting suits.

The rule should then be that an acceptor should be free to increase any bid that he had already made or accepted, regardless of what bids had intervened, but that he should be barred from shifting when he was only an acceptor.

For example. If he has bid a spade and afterward accepted a heart, he should be allowed to bid more spades or hearts, but not to shift to clubs, diamonds or no-trumps if the heart acceptance has not been overcalled and accepted. Under the present rules the bidder can always shift after he has been accepted.

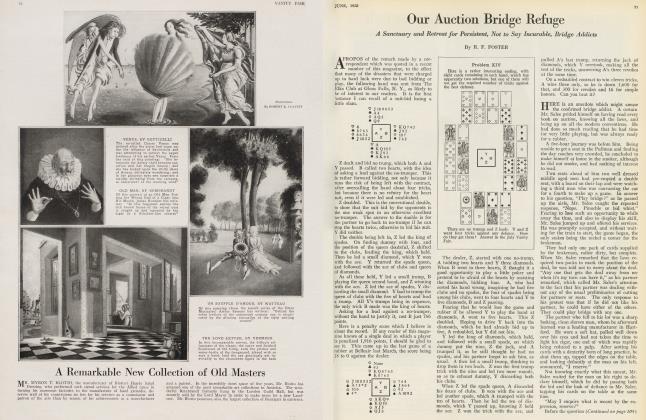

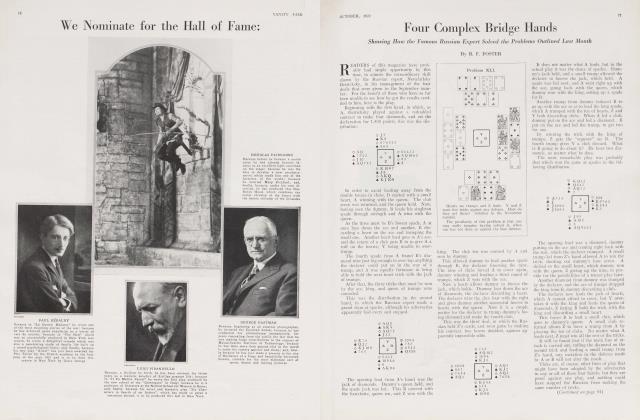

To illustrate this point, take the following hand, which was first played in a duplicate match at the Knickerbocker and afterward at pirate by four experts who were trying out the suggested rule of scoring only the bid.

At auction Z dealt and bid no-trump, Y took him out with two spades and they made five odd. Under the bid-limit rule, all they could have scored would have been the two odd they bid, 18 and 18; 36 points, instead of 45, 18, 125, a difference of 152.

No one would for a moment suggest that Y should have taken his partner out with a bid of four or five spades; nor that the dealer should have increased Y's bid to four or five, the game being auction. At pirate, the bid of a game value was arrived at in this way:

Z has the choice of two bids, a one-try no-trumper or the heart. As the try-out shows more, he selects that for the first bid and says one diamond, accepted by Y. The no-trump was also accepted by Y and Z then bid the heart, which no one could accept, as no one could stop that suit.

If it is the rule that an unaccepted bid is void and bars the bidder from going further, and that an acceptor can not increase or shift, the hand must be played at no-trump, and all Y and Z can make is two odd.

But under the experimental rule that the acceptor could increase any previous bid or acceptance made by himself, Y has another chance. He can read the possibilities of the hands this Way. Z is weak in diamonds, but Y must make at least one trick in that suit. Z's no-trump bid shows a club trick. His heart bid shows a suit of four cards only (or he would have bid hearts originally) but if no one has three to the queen or four to the jack or ten, Z should be able to make three hearts with his reentries. He is marked with the ace of spades, so that between them they should make five in that suit. On this reckoning Y bids four spades and scores a game.

Some Minor Changes

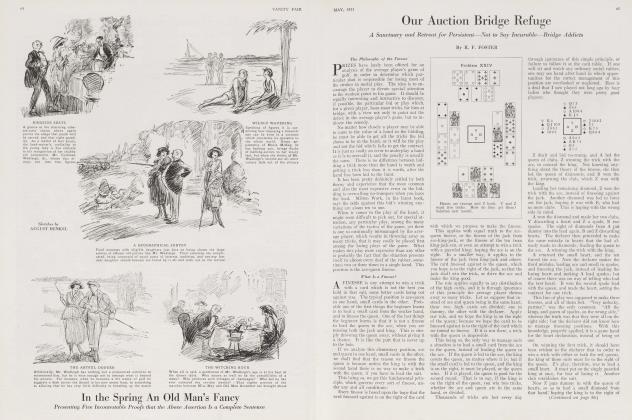

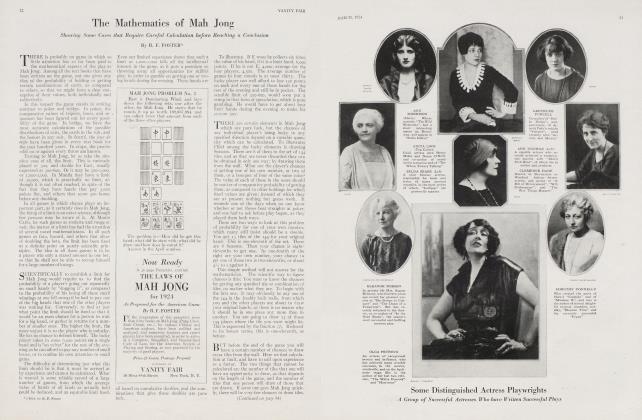

AMONG the minor changes suggested is one that has been quite largely adopted by teachers and players. This is to confine one-try no-trumpers to the minor suits, clubs and diamonds, and to stick to the major suits for trumps, instead of making them part of a no-trumper. Take this illustration:

At auction Z dealt and bid no-trump. A led a small spade and the hand worked out very badly, for Z. At pirate, instead of bidding a spade, Z bid the club, accepted by Y. Then Z accepted B's spade and also accepted A's two heart bid, as he could count A for tricks outside hearts.

A can not have more than 6 values in hearts (A Q 10), and must have 2 or 3 in diamonds or spades. Z can kill that club king in his acceptor's hand by leading through, so when all pass the heart acceptance, Z, under the bid-again rule, went four hearts, accepted by A and they made five.

There have been other suggestions, such as the introduction of a solo bid, and various schemes for nullos, but for the present it seems best to leave the game as it is. By the time winter sets in again, we may very well feel confident that we shall have a large fund of experience to guide us.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now