Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

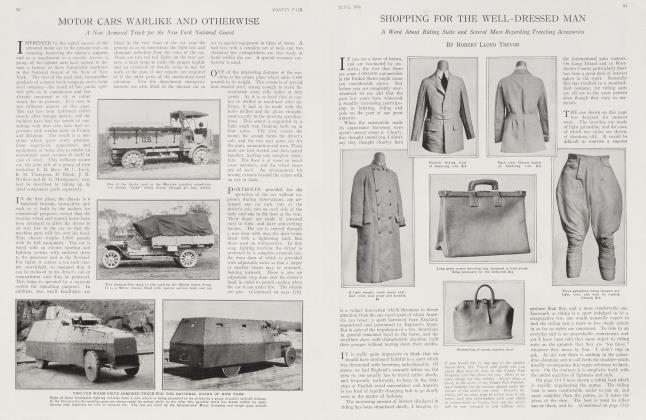

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSHOPPING FOR THE WELL-DRESSED MAN

Hints as to What Men Ought to Wear, Whether They Will or Not— A Few Words on "1916 Models" and Some Thoughts by an Old-time Authority on Hats

Robert Lloyd Trevor

A teller addressed lo Vanity Fair will bring you in return the addresses of the shops where any of these articles may be bought, or the answer to any perplexing question with regard to men's attire.

The Vanity Fair Shoppers will at all limes do your buying for you at no extra charge

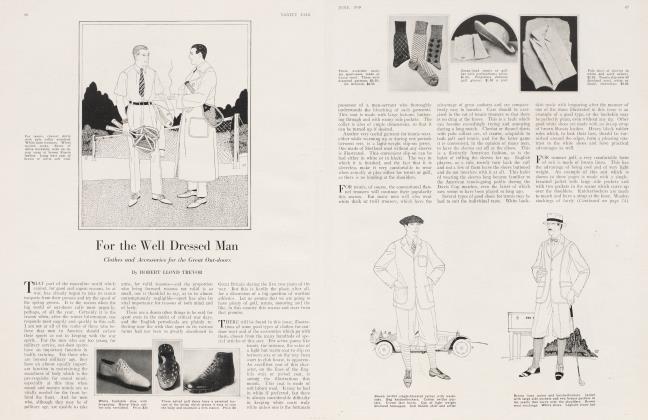

IT IS always gratifying to have one's opinions coincide with those of others whose ideas one values. And this kind of gratification comes to me from two sources. I had intended, for instance, a few' -weeks ago, to write something in this department, regarding the absurd misuse of the sports-shirt, as exhibited in New York and other cities. Then along came that clever artist, Miss Myrtle Held, bringing with her the sketches reproduced above. They tell far more in their way, than I could in mine. Miss Held, in the words of the poet, "beat me to it."

There have been shirts for sporting wear shown in Vanity Fair. They are essential to the field attire of every man. But they are for sporting w?ear only, for the links, or the tennis courts, for tramping or boating, but it is the height of incongruity to wrear them in town. One might as well wear tan shoes and a pink tie with white flannels in the Easter parade on Fifth Avenue.

Again, I had made a mental note to repeat something I said last year about hats, and the desirability of varying one's headgear so that it will harmonize with the rest of one's clothes. Then, one day, while loitering through the delightful essays in Mr. E. V. Lucas's "Loiterer's Harvest," I came upon the same idea. Mr. Lucas had found it in the autobiography of one Henry Melton, a hatter, published in London at about 1864. The extract quoted in "Loiterer's Harvest" contains part of an account of a visit by Mr. Melton to a certain nobleman, who was popularly known as the last of the Dandies.

I wish I could reprint all of it, for it has a charming naivete. But, since space will not permit my doing so, you must be content with the merest snatches of it.

"On a table in the Count's dressing room I observed some fourteen hats lying all ready for wear. The Count seemed rather pleased with my zeal; and'this kind reception, as well as his refined and elegant manner, encouraged me in the discussion which ensued upon the subject of hats, and ended in our mutually agreeing that the desiderata in regard to a hat consisted in its being light, although of a substance sufficient to retain its shape. . . . That it should be waterproof; that it should be so made as to ensure comfort; that the shaping and blocking and trimming were merely matters of taste and fashion of the period, but that the style of the hat should, nevertheless, be carefully studied, as much as possible, to make the wearer look like a gentleman." . . .

And again: "No part of the Count's personal attraction was more studied by him than his hat, nor was it the less noticed and admired by the public. His taste was marvellous, and his quickness of eye in costume beyond all that can be imagined. . . .

"As an illustration of the fact, his hats varied in dimensions to suit his coats. For his lighter, cut-off riding-coat, he wore his hat smaller in all dimensions than for the thicker overcoats. . . .

"Need I say that the consummate acuteness of this idea of a distinct hat for a particular coat left a deep and lasting impression of its importance on myself? Indeed, the mere enunciation of it made the fact self-evident, that a hat should most assuredly suit the width of shoulders or figure as much as the face."

TO which words of wisdom I may add that color also plays a part in the scheme. Verb. sap.

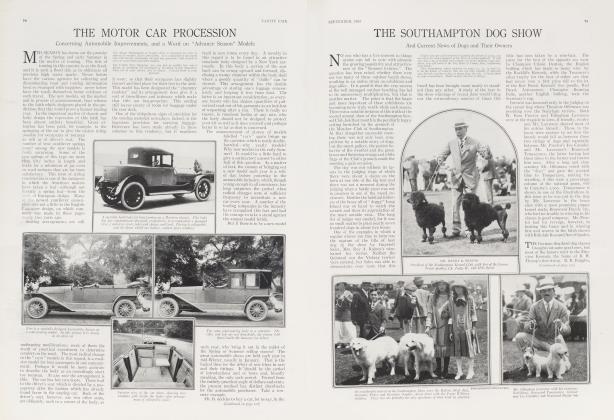

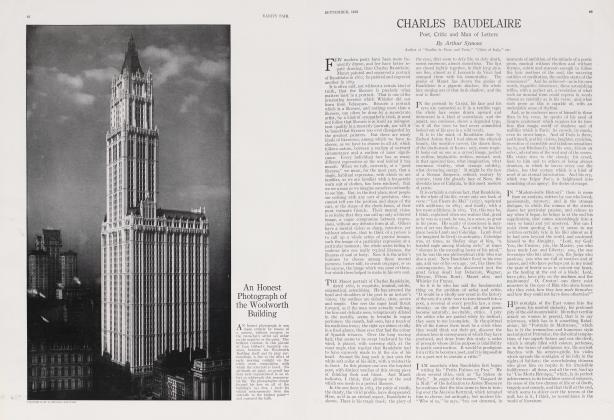

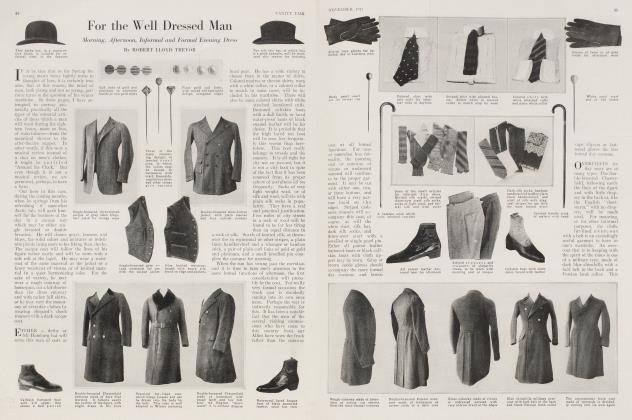

There are four hats on this page. I consider them to be the best of the coming season's crop. And they embody Mr. Melton's desiderata namely: lightness, but sufficient substance to retain their shape; the quality of being as nearly waterproof as felt hats can be made; and comfort. They range in color—the soft hats, of course, not the derby—from dark browns and blues to light browns and grays and greens. The two at the top may be worn with either the puggaree band, as shown, or the plain band with a neat, rather square bow at the side, as in the hat at the bottom. A man who cares about his appearance might do well to possess himself of all four of them. By judicious selection of colors, with regard to the colors of his suits, he would render his informal wardrobe, so far as his headgear is concerned, absolutely complete. Hats for formal dress will be dealt with in a later issue. And for the sake of leaving no stone unturned in an effort to supply something for everybody, I shall put some more informal day hats in my October article.

Now, if you will put your agile mind to the test, we will slide down from the lofty eminence of hats to the common or garden—or sidewalk —topic of shoes and boots. By boots I don't mean those long, large, rubber sheaths that drape themselves so gracefully around the thighs of snow-shovelling suburbanites. I mean the pretty little things usually known as "high-shoes." And I call them boots for reasons of economy of space.

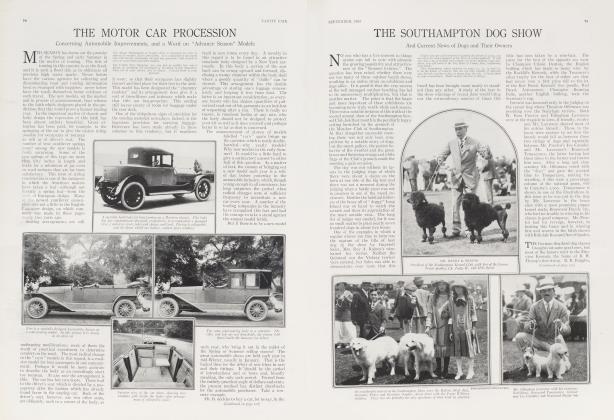

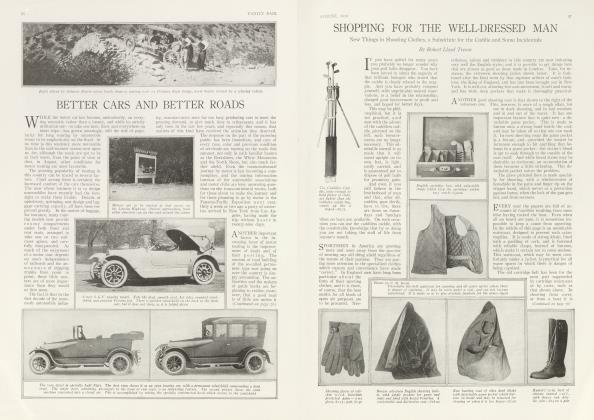

The boots shown here are essentially for informal wear, with a sack suit. The first one is of black calf, with a wing tip (it may also be had in brown) and is a good boot for the younger man who happens to like something light in weight, and not too staid. The middle one is considerably heavier, and has a blucher cut top. It is more of a rough weather boot. And the lowest one is just a boot, in black or brown, very straight, with a somewhat squared French toe. Though it is not an old man's boot, it is one that older men may wear without feeling too coy. At the top of the column is a heavy, dark tan shoe, for the man who likes freedom at the ankles all the year round, and doesn't feel the cold. All the three boots and the shoe are on comfortable, unobtrusive lasts; the kind of last, in fact, that is sensible and never gets out of date.

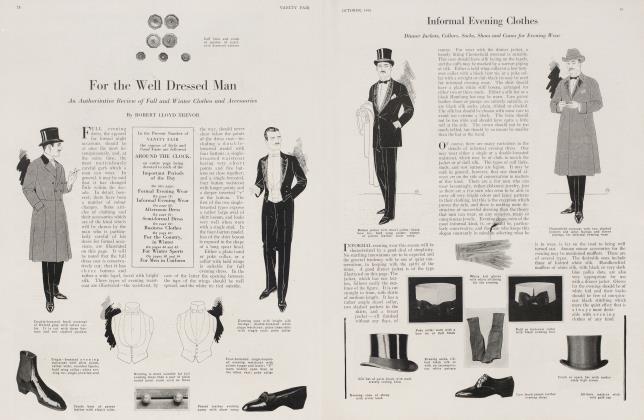

And now we come to the actual clothes, and the tendencies in men's fashions—that horrific word—and here is my chance to say something that a lot of people will probably dislike.

MEN'S clothes have reached a stage in their evolution where, barring a reversion to the silks, satins and ruffles of an earlier day, or a sudden plunge into a new, exciting kind of drapery yet to be discovered, they can evolve no more. As a matter of fact this point was reached a number of years ago—but not in America. Man has patiently allowed the tailors to experiment and change, to cut and chop, to pad out and to draw in—briefly, to try everything they could imagine.

We have survived years of loose, long coats and baggy trousers and light, short coats and narrow trousers. Our lapels have been lengthened and shortened, widened and narrowed; our sleeves have been cuffed and uncuffed. Our waistcoats have buttoned high up under our chins and at other times have had but three buttons, beginning somewhere near the diaphragm. And what has it all come to? Simply this:

Continued on page 110

Continued from page 73

Men have found that they are comfortable and that they look well in coats that are fairly short; that are slightly drawn in a little above the waist; that have no padding anywhere; that have moderately narrow sleeves and moderately long lapels.

Men have decided that their waistcoats should have neither abnormally small openings, nor abnormally large ones, but, rather, a fair sized opening that discloses a decent expanse of necktie.

Men have concluded that trousers need be neither billowy nor skin-tight, but merely wide enough to afford comfort at all times.

And there you are.

You may like a three button coat, with pointed lapels. Your best friend may prefer a two button coat with notched lapels. I happen to cherish a predilection for a four-button coat with short lapels. Very well, we can all have what we want, you, your friend and I. No one shall say to you: "You can't wear a threebutton coat; and pointed lapels are impossible, because So and So, of Fifth Avenue, is not making them this season."

Just so long as you stay within the bounds of reason

A letter addressed to Vanity Fair will bring you in return the addresses of the shops where any of these articles may be bought, or the answer to any perplexing question with regard to men's attire. The Vanity Fair Shoppers will at all limes gladly do your buying for you at no extra charge and good taste, just so long as you abstain from padded shoulders, and inordinate tightness, and scalloped designs on your pockets and all exaggerations of detail, you are as safe as a toyboat in a horse-trough.

ONE of the best tailoring houses in the country, an establishment which probably clothes more well-dressed men than any in New York, makes its suits on the same pattern year in and year out. And so far as I can discover, most of the other good tailors are working on much the same plan. There is no such thing as a 1915 or 19iO model.

Instead of trying to keep up with the minor changes that make up the so-called fashions, you will do better to find a cut that thoroughly suits you and stick to it. If you pay due attention to what is appropriate to your age, complexion, build and to the purpose for which different types of clothes are specially designed, you will always be well dressed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now