Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

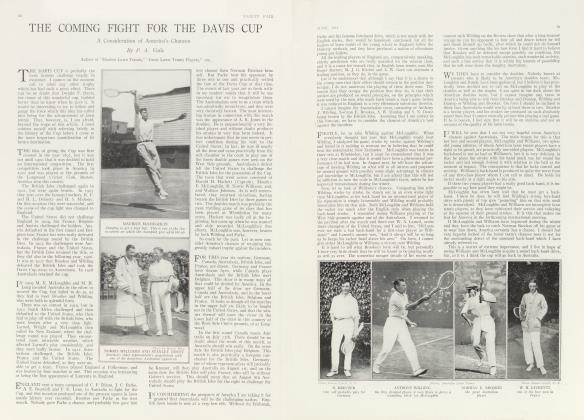

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA NEW CLASSICAL NOTE IN PHOTOGRAPHY

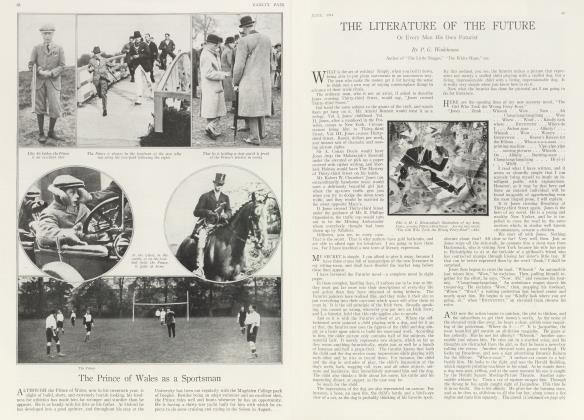

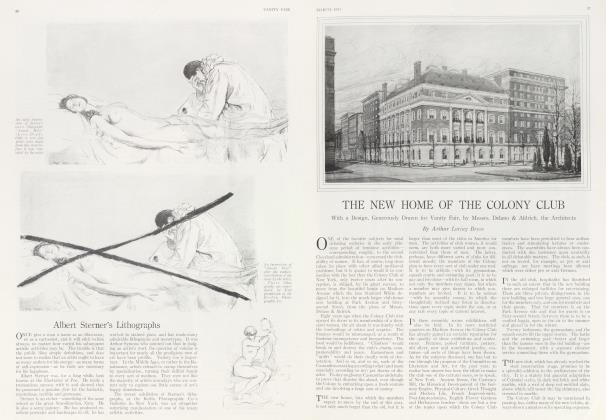

Arthur Loring Bruce

With a Series of Recent Camera Studies, Made in California, by Annie W. Brigman

THE poetical and wholly enchanting belief of the Greeks was that the magical and mysterious moods of nature were somehow called into being and presided over by a group of beautiful nymphs: naiads, or nymphs of the rivers and streams; oreads, nymphs of the wind-swept hills and lofty mountains; and dryads and hamadryads, nymphs of the ancient groves, and forests, and trees.

The Greeks loved nature passionately. They loved the long caravans of autumn clouds, the fervid flames of summer, the shell-like murmurings of the woodland groves, the silent evenings, and the hoarse-sounding sea, but their fancies liked to people all the manifestations of nature with nymphs and quasi-human goddesses. They loved nature, but they also loved beautiful and nobly formed women, and so, being true artists and poets, they made mysteries of them both. They never sought to understand nature in the sense that we study and understand it to-day. They wanted nature always to be remote, unexplained; sanctified for them by a mystery more magical and mighty than they could well comprehend. It has only been in the last century that poets have treated nature at all, shall we say?—intimately. Cowper, Shelley, Keats and Wordsworth were the great forerunners of our altered, more calculated, and more inquiring appreciation of nature.

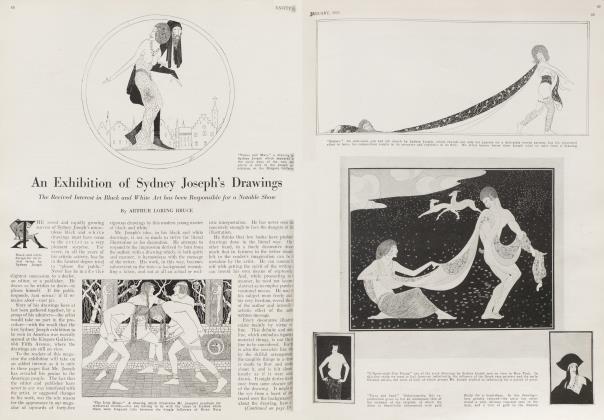

WHAT is so interesting in the photographic studies of Mrs. Brigman is her complete, if quite unconscious, reversion to the Greek ideals of nature. She is a true artist and to her the human figure, the figure of a young and beautiful woman, presides naturally and serenely over the blue vault of heaven, over rocks, streams, pines, and the peaks of aged mountains. She has peopled her sunny and azure California with Fates and Fauns; with Nymphs, eternally graceful, eternally chaste, eternally young. But see how indissolubly married they are to the earth, to the forests and hills, and to the misty mountain tops of which they seem so inevitably a blended part. They become—as if Ovid had metamorphosed them all—brides of the valleys, rivers and trees. There is nothing human about them, no touch of actuality, no taste of the perplexing turmoil of to-day.

frontispiece, the youthful figure seems actually to haunt and inhabit the branches of the pine, just as the hamadryads themselves found sanctuary—in the poetic minds of the Greeks—in the trees of old. In the imperishable myths of Greece it was an impious act wantonly to destroy a tree, and this solely because the ever youthful hamadryads perished with the trees they inhabited. And so, men who hewed them down were made desperately to suffer for it—witness the fate of the unfortunate Erisichthon. And this gallant belief of the Greeks gave Landor his inspiration for "Hamadryad," the loveliest of all his poems—and one of the loveliest in our language.

In the pictures on page 28, Mrs. Brigman is almost at her best. The upper photograph is of Daphne, who, pursued by Apollo, calls upon Peneus to change her form. She pauses in her flight and realizes that she is being metamorphosed into a tree, her legs are encased in bark and her feet have taken root in the ground.

The lower photograph, page 28, represents the nymph Orythyia, beloved of Boreas, the god of the restless and blustering north wind. She is shown in the fitful currents of the gale, gazing over the wind-swept valleys of Greece, toward the twilight of the North, where her lover is in hiding. Almost she seems to invoke the airy gusts and torrents of the sky, as Shelley once invoked them.

Because she is a true artist, see how dramatically Mrs. Brigman has pictured Clotho and Clytie. They are brooding, elemental spirits, mysterious, aloof, full of a nameless and ancient woe.

Perhaps Mrs. Brigman's greatest contribution to modern photography is her tacit acceptance of the truth that, in the noblest and serenest figure-and-landscape compositions, the human form must never be divorced from the mood or spirit of the scene that surrounds it. Too often, in outdoor figure painting and photography, nature and human life seem to be wilfully at odds. The figure should blend and mingle harmoniously with the scene, and never defy, dominate or overbalance it. Between the two there should always be a certain unified artistic suavity or rhythm, just as there is in the works of all the great "figure-landscape" painters, whether of the ancient and artless school of Umbria, or of Bastien Lepage's more modern and sophisticated school of plein-air.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now